THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY

the bpp on the dugout

Some of our episodes featuring interviews with Black Panther Party Members or covering their era of politics

HOW THEY STARTED

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in October 1966 in Oakland, California, by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, two students at Merritt College who were deeply influenced by the teachings of Malcolm X, the writings of Frantz Fanon (The Wretched of the Earth), and the systemic violence they witnessed daily in West Oakland. After watching police brutalize Black residents with impunity, Newton and Seale drafted the 10-Point Program — a set of demands and beliefs that outlined their revolutionary vision for Black liberation. Their first major organizing tactic was to form armed patrols to monitor and observe police officers during traffic stops and street encounters. Using California’s open-carry laws, they followed officers while carrying legally registered firearms and law books, asserting both their Second Amendment rights and their right to self-defense.

This practice of policing the police quickly gained national media attention and drew the ire of local authorities and the FBI. But the Panthers’ strategy went beyond armed resistance. By 1967, the organization had grown to include a formal membership structure, daily political education classes, and connections with anti-imperialist movements abroad. Newton described the Party as a revolutionary vanguard rooted in Black self-determination, anti-capitalism, and internationalism. Their approach was intentionally dual: resist state violence through direct action and simultaneously build alternatives through community-led survival programs. What began as two young organizers in Oakland rapidly evolved into a national network of chapters in cities like Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, and beyond.

KEY MEMBERS OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY

HUEY NEWTON / BOBBY SEALE / ERICKA HUGGINS / ELAINE BROWN / BOBBY HUTTON / ELDRIGE CLEAVER / FRED HAMPTON / JAMAL JOSEPH / ASHANTI ALSTON

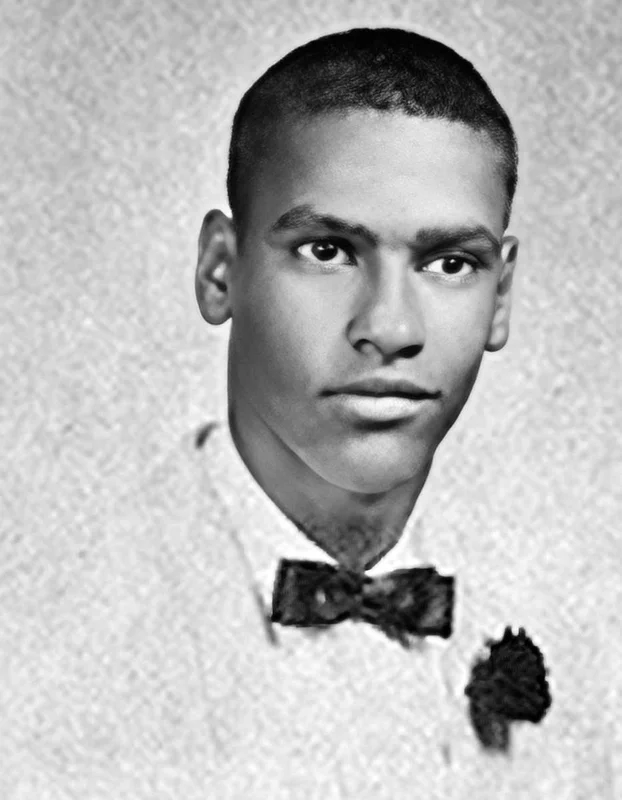

HUEY p. newton

CO-FOUNDER OF BLACK PANTHER PARTY

Huey P. Newton was born on February 17, 1942, in Monroe, Louisiana, and grew up in the segregated streets of West Oakland, California. Early experiences with poverty, systemic racism, and police harassment shaped his political consciousness. In 1966, at the age of 24, he co-founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense with Bobby Seale, creating the Ten-Point Program to demand justice, housing, education, and an end to police violence. By 1967, Newton’s arrest in the death of Oakland police officer John Frey sparked the global “Free Huey” campaign, turning him into a symbol of Black resistance, chronicled in The Black Panther newspaper and Elaine Brown’s memoir A Taste of Power.

From 1968 through the early 1970s, Newton led the Panthers in expanding their work beyond self-defense to community programs. In 1969, the Party launched its Free Breakfast for Children program and opened health clinics, sickle-cell testing centers, and legal aid offices, all designed to support oppressed communities. During this period, Newton developed his political theory of “revolutionary intercommunalism,” arguing that global Black and oppressed communities were connected under U.S. imperialism. His ideas drew on Malcolm X, Frantz Fanon, and his own experience organizing in Oakland, and are documented by scholars such as Alondra Nelson in Body and Soul.

Huey Newton Interview (1989)

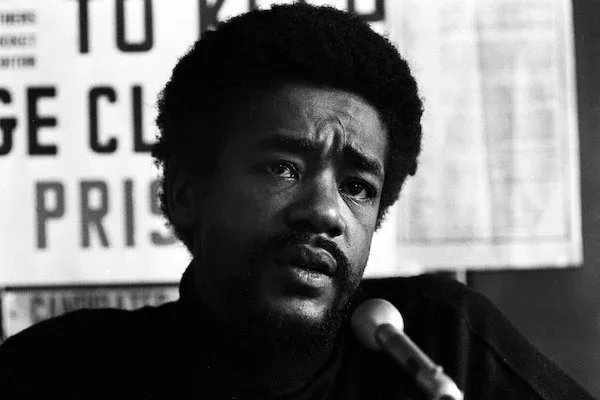

BOBBY SEALE

CO-FOUNDER OF BLACK PANTHER PARTY

Bobby Seale was born on October 22, 1936, in Liberty, Texas, and raised in Oakland, California, where segregation, poverty, and police violence shaped his worldview. In 1966, he co-founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense with Huey P. Newton and helped craft the Ten-Point Program demanding justice, housing, education, and an end to police brutality. As the Party’s national spokesperson, Seale traveled the country to organize chapters, raise funds, and shine an international spotlight on Black struggle—a rise captured in his memoir Seize the Time.

In the late 1960s, Seale became a target of the state. He was one of the “Chicago Eight” in 1969, charged with conspiracy and inciting riots at the Democratic National Convention, a stark example of the government criminalizing Black political activism.

Staggerlee: A Conversation with Black Panther Bobby Seale (1970)

ELAINE BROWN

Chairwoman (1974–1977)

Elaine Brown (b. 1943) served as Chairwoman of the Black Panther Party from 1974 to 1977, becoming one of the first women to lead a major revolutionary organization in the United States. She directed national programs, including community survival initiatives like free breakfast programs, health clinics, and youth education, while pushing the Party to center women’s leadership and gender equity in its organizing. Brown also chronicled her experiences and the inner workings of the Party in her memoir A Taste of Power, offering a firsthand account of revolutionary politics, state repression, and the challenges of leading a movement in a male-dominated space.

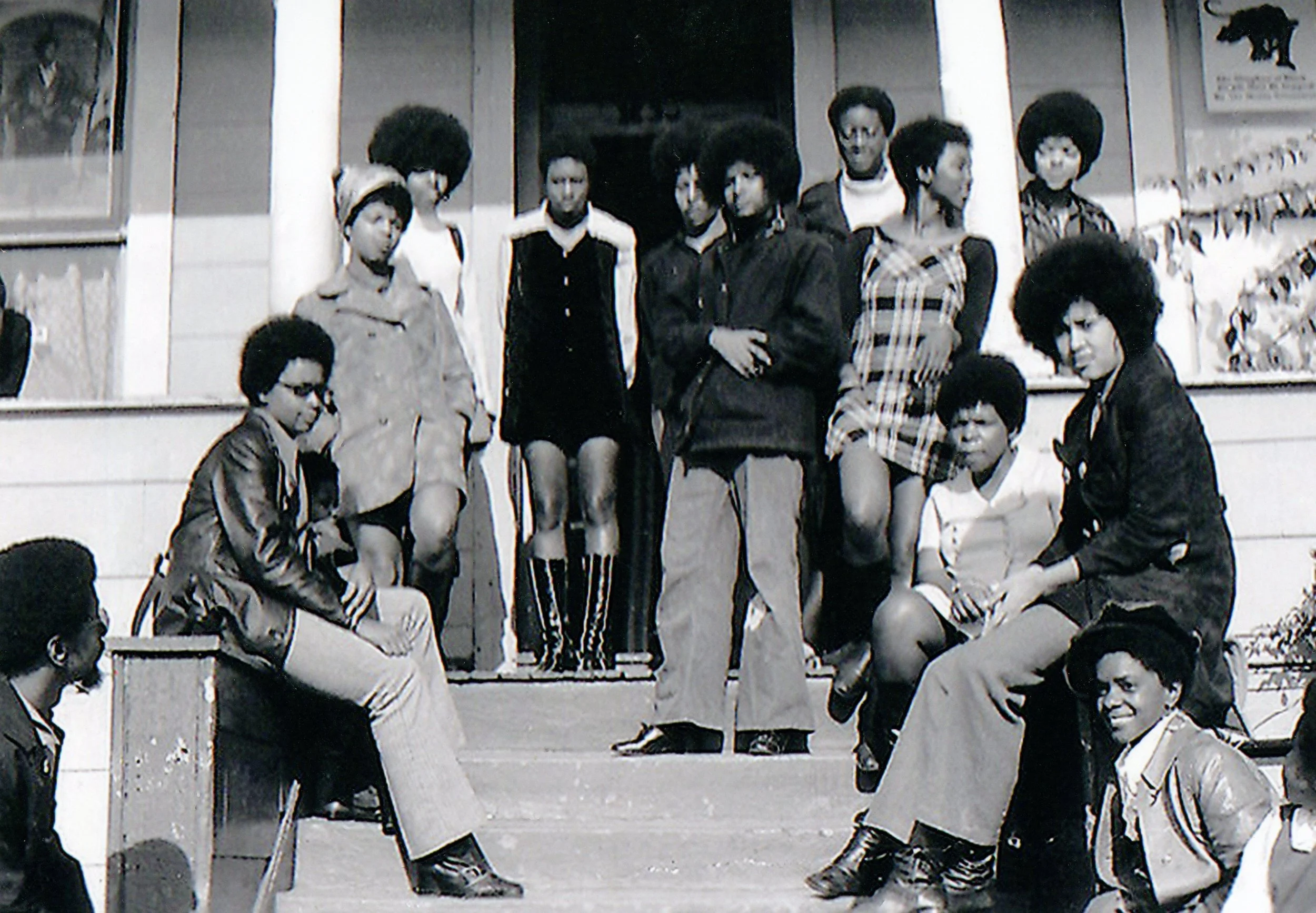

the black panther party, feminism, and the labor of black women

Our Story“It is estimated that 6 out of 10 members of the Panthers were women. These women worked to build communities and enact social justice, providing food, housing, education, and healthcare, all while making headlines for agitating, protesting, and organizing. But their stories had never been fully told.”

- bind magazine

On The Question Of Sexism Within The Black Panther Party (Excerpt)

by Safiya Bukhari

“In its brief history (1966-1973) [1] of seven years women had been involved on every level in the Black Panther Party. There were women, like Audrea Jones, who founded the Boston Chapter of the Black Panther Party, women like Brenda Hyson, who was the OD (Officer of the Day) in the Brooklyn Chapter of the Black Panther Party, women like Peaches, who fought side by side with Geronimo Pratt in the Southern California Chapter of the Black Panther Party, Kathleen Cleaver who was in the Central Committee, and Sister Rivera who was one of the motivators behind the office in Mt. Vernon, NY. By the same token there were problems with men who brought their sexist attitudes into the organization. Men who refused to take direction (orders) from women, and we had a framework established to deal with that but because of liberalism and cowardice ,as well as fear, a lot of times the framework was not utilized.

On the other hand, some women sought to circumvent the principled method of work and utilize their femininity as a way to achieve rank and statue within the Party.

They also utilized their sexuality to get out of work and certain responsibility. This unprincipled behavior within the Party (just as on the streets) undermined the work of other sisters who struggled to deal principly. Thus, there were three evils that had to be struggled with, male chauvinism, female passivity and ultra femininity (the I'm only a female' syndrome).

The advent of the Women's Liberation Movement during the late 60's sought to equate what was happening with white women in this society to the plight of Black women. The white women were seeking to change their role in society vis-a vis the home and the work place and to be seen as more than just a mother and homemaker. They wanted to be afforded right to the work place or whatever role they sought to play in society. But our situation was different, we had been working outside of the home and supporting our families. We had been shouldering the awesome responsibilities of waging a struggle against racist oppression and economic exploitation since we had been brought to these shores on the slave ships. Our struggle was not a struggle to be liberated so we could move into the work place, but a struggle to be recognized as human beings.”

Women of the Black Panthers : A Discussion In The Wake Of Huey Newton's Death.

A Bay Sunday broadcast on 25th of August 1989 presented by Barbara Rogers, featuring a discussion with Angela Davis, Ericka Huggins and Jonina Abron, in the wake of Huey Newton's Death.

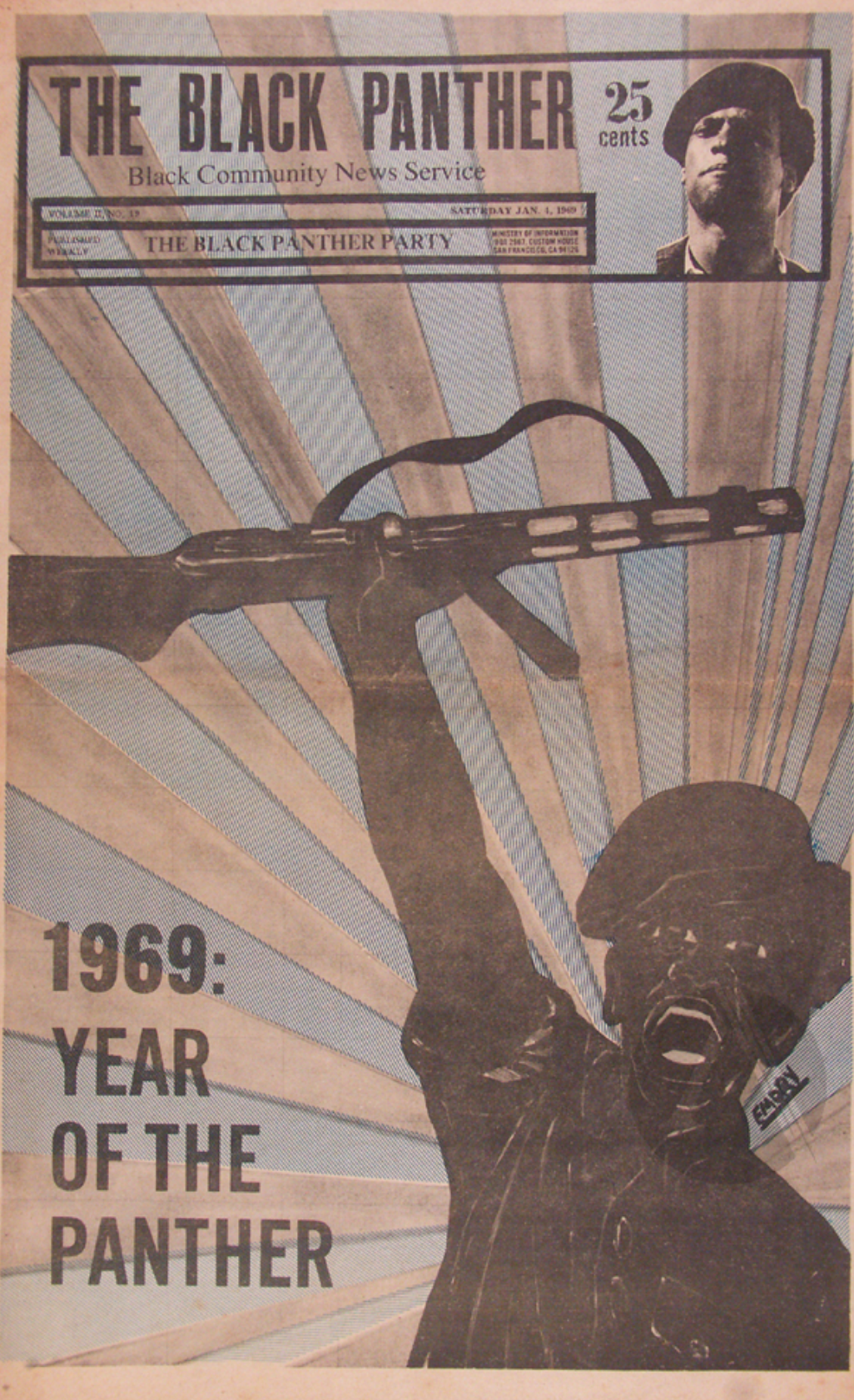

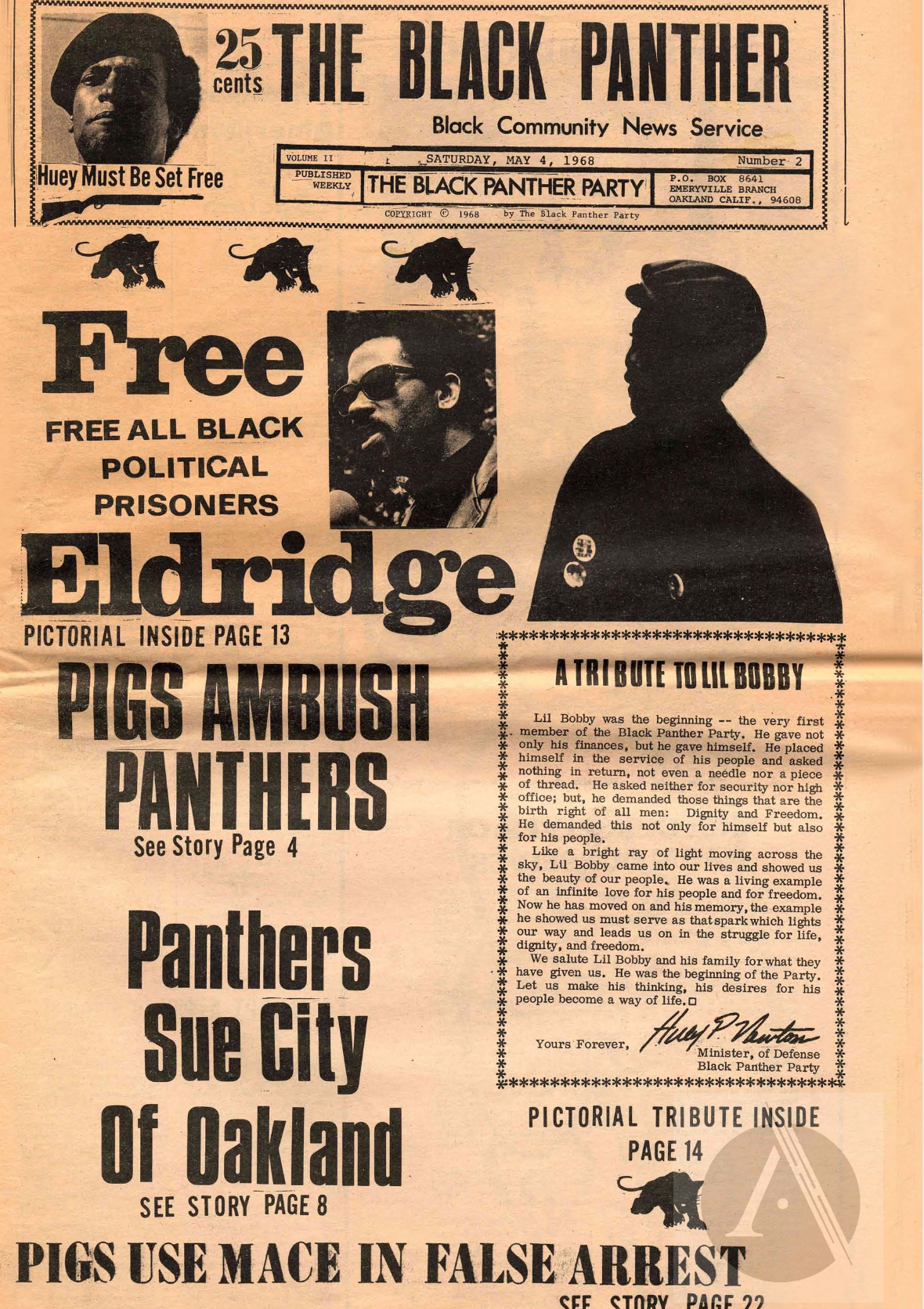

tHE BLACK PANTHER NEWSPAPER

In 1967, the Black Panther Party launched The Black Panther newspaper to serve as a mouthpiece for the movement and a direct challenge to the misinformation spread by mainstream media. Initially edited by Eldridge Cleaver and later by figures like Judy Juanita and David Hilliard, the newspaper became a vital communication tool between chapters and with the broader public. It reported on police killings, community struggles, international liberation movements, and internal Party work. At its peak in 1970, the paper had a weekly circulation of over 139,000 copies and was published in cities across the U.S., including Oakland, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles (Bloom & Martin, 2013).

The Black Panther was more than a newsletter — it was a political education tool. Each issue opened with the Party’s 10-Point Program and featured original artwork by Minister of Culture Emory Douglas, whose illustrations became iconic representations of Black resistance. It was sold for 25 cents by rank-and-file Party members, who often used the paper to engage community members in political conversation and organize locally. The newspaper also ran coverage of anti-colonial struggles in Algeria, Vietnam, Mozambique, and Palestine, linking Black liberation to global resistance against imperialism.

In 1974, JoNina Abron (later JoNina Abron-Ervin) became the final editor of The Black Panther newspaper. She had joined the Party in 1972 while attending graduate school and took over editorial leadership during a pivotal period when the BPP had centralized operations in Oakland and shifted toward survival programs like the Oakland Community School. Under Abron's direction, the newspaper maintained a sharp focus on prison conditions, political prisoners, women in the movement, and Black self-determination. She oversaw the publication until it ceased in 1980, and her leadership preserved the Party's political clarity during years of FBI harassment and internal reorganization (Abron-Ervin, 2020).

READ A BPP NEWSPAPER ARCHIVE

bpp influenced…

the dalit panthers

The Dalit Panther Party was founded in July 1972 in Mumbai (then Bombay), India, as a militant organization committed to dismantling the deeply entrenched caste system and fighting for the rights of Dalits—the socially ostracized “untouchable” communities historically subjected to brutal oppression. The Panthers emerged in response to the slow and often tokenistic reforms post-Indian independence, asserting a bold new form of Dalit resistance grounded in self-respect, cultural pride, and political activism.

Drawing inspiration from the Black Panther Party, established in the United States in 1966, the Dalit Panthers adapted the model of revolutionary self-defense, community organizing, and cultural assertion to India’s unique caste context. Although no formal organizational ties existed, the Dalit Panthers identified with a global movement against racial and caste oppression, situating their struggle within international anti-colonial and human rights frameworks.

Founding and Ideological Roots

The movement was established in June 1972 by poets and activists Namdeo Dhasal, J.V. Pawar, and Raja Dhale, among others. Dhasal, a prominent Marathi poet, was particularly influenced by the Black Panther Party's emphasis on self-defense, cultural pride, and revolutionary politics. The Dalit Panthers adopted a similar approach, combining Marxist ideology with Ambedkarite principles to address the systemic oppression faced by Dalits.

Their manifesto, released in 1973, rejected mere reforms and called for a complete revolution to overthrow the caste-based social order. It emphasized the need for a radical transformation of society, advocating for the empowerment of Dalits and other marginalized communities.

history of the dalit panther party

the dalit panthers: a timelime

1947 – Indian Independence and Constitutional Promise

India gains independence from British colonial rule. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, a Dalit leader and principal architect of the Indian Constitution, ensures that the new constitution outlaws “untouchability” (Article 17) and provides affirmative action (reservations) for Scheduled Castes (Dalits) in education, employment, and political representation. This legal framework aims to dismantle caste discrimination officially.

1950s–1960s – Persistent Discrimination Despite Legal Protections

Despite constitutional guarantees, caste-based discrimination remains pervasive, especially in rural areas and urban slums. Dalits continue to be socially ostracized, economically marginalized, and subjected to violence and segregation. Political gains are limited, and many Dalits remain trapped in cycles of poverty and exclusion.

Late 1960s – Rise of Dalit Assertion and Cultural Awakening

A growing Dalit literary and social movement develops, especially in Maharashtra, fueled by the works of writers like Baburao Bagul and poets such as Namdeo Dhasal. This period marks an awakening of Dalit consciousness, shifting from reformist approaches toward a more militant and radical critique of the caste system and broader social inequality.

June 1972 – Formation of the Dalit Panther Party

In Siddharth Nagar, a Dalit-dominated neighborhood in Mumbai, a group of young Dalit intellectuals, poets, and activists—including Namdeo Dhasal, J.V. Pawar, and Raja Dhale—formally establish the Dalit Panther Party. Inspired by the militant Black Panther Party in the U.S., they seek to confront caste oppression head-on, rejecting gradual reform and advocating for revolutionary change. Their manifesto calls for self-defense, cultural pride, and radical transformation of Indian society.

1973 – Manifesto and Rapid Growth

The Dalit Panthers publish their manifesto, articulating a Marxist-Ambedkarite critique of caste and capitalism. The movement spreads beyond Mumbai, attracting a growing membership among Dalit youth frustrated with slow progress and systemic violence.

February 1974 – Worli Riots

During a Dalit Panthers rally in Mumbai’s Worli area, tensions flare when a Panther activist is killed by stone-throwing upper-caste opponents. The clash escalates into violent riots involving Dalits, upper-caste groups, and police repression. The riots expose the deep social fissures and heighten the Panthers’ visibility as defenders of Dalit rights and dignity.

1975–1977 – Emergency and State Repression

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declares a national Emergency, suspending civil liberties. The Dalit Panthers face intensified crackdowns: leaders are arrested, activists intimidated, and publications censored. This period severely weakens the movement’s organizational strength.

Late 1970s – Internal Divisions and Decline

Factionalism grows within the Panthers as some members opt for electoral politics and alliances with mainstream parties, while others maintain a radical stance. The state’s repression, ideological splits, and political co-optation lead to fragmentation and decline of the movement as a united force.

Early 1980s – Disbandment and Legacy Formation

The Dalit Panthers officially disband by 1988, but their cultural and political legacy persists. Members continue influencing Dalit politics and literature, inspiring subsequent generations of activists and writers.

2000s–Present – Enduring Influence and Commemoration

The Panthers are remembered as pioneers of militant Dalit resistance. Their literary contributions, particularly Namdeo Dhasal’s poetry, are celebrated for reshaping Dalit identity and political consciousness.

In 2022, the 50th anniversary of the Panthers’ founding is marked by events in India that bring together former Dalit Panther leaders and Black Panther veterans from the U.S., underscoring their shared commitment to combating systemic oppression globally.

An Excerpt From The Dalit Manifesto

Today we, the 'DaHt Panthers', complete one year of our existence. Because of its clear revolutionary position, the 'Panthers' is' growing in strength despite the strong resistance faced by it from many sides. It is bound to grow because it has recognized the revolutionary nature and aspirations of the masses with whose smiles and tears it has been bound up since its inception. During last year, motivated attempts have been made, especially in the far comers of Maharashtra, to create misunderstandings about our members and our activities. Misconceptions about the objectives of the 'Panthers', about our commitment to total revolutionary and democratic struggles, and about its policies, are being spread. It has, therefore, become necessary clearly to put forward our position. Because, 'Panthers' no longer represent an emotional outburst of the dalits. Instead, its character has changed into that of a political organization. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar always taught his followers to base their calculations about their political strategy on deep study of the political situation confronting them. It is necessary and indispensible for us to keep this ideal before us. Otherwise we might mistake the back of tortoise for a rock,' and may be drowned in no time.