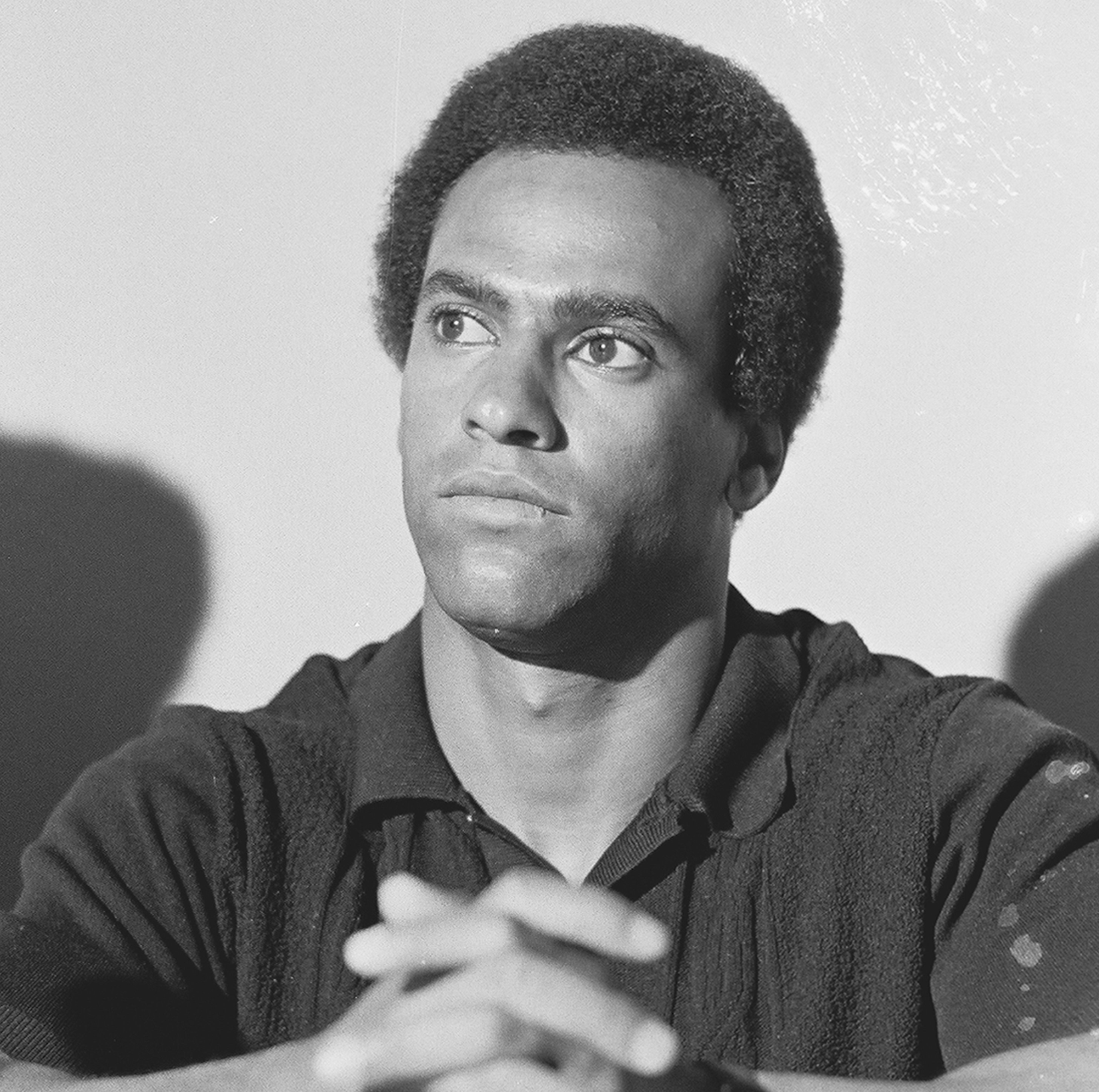

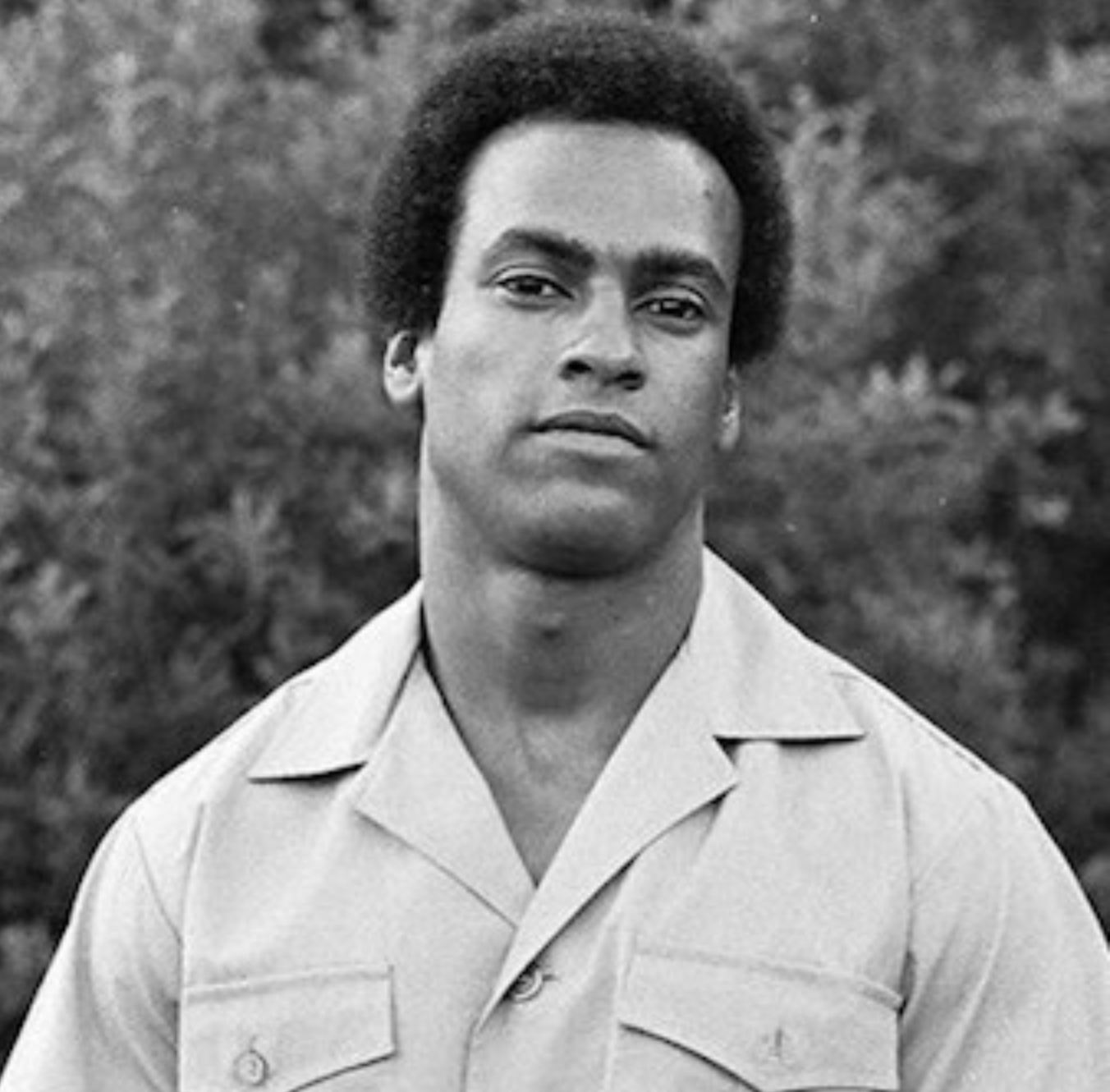

huey newton (1942–1989)

Huey Percy Newton co-founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California, in 1966, alongside Bobby Seale. Born in Louisiana and raised in Oakland, Newton grew up confronting systemic racism and poverty. Despite struggling in school, he educated himself in political theory and law, drawing from thinkers like Frantz Fanon, Mao Zedong, and Malcolm X. As Minister of Defense, Newton articulated the Panthers’ core philosophy through the Ten-Point Program, which called for freedom, employment, housing, education, and an end to police brutality. Newton helped popularize the practice of armed patrols to monitor police activity, which made the Panthers both feared and admired. He also emphasized “survival programs,” such as free breakfast for children, health clinics, and liberation schools, as practical expressions of revolutionary politics. Newton’s leadership was often contested by state repression and internal tensions; he faced multiple arrests and long stretches of incarceration. After the decline of the Party, he completed a Ph.D. in social philosophy at UC Santa Cruz, writing on the concept of “revolutionary intercommunalism.” Newton was murdered in Oakland in 1989, a reflection of both his tumultuous later years and the ongoing violence surrounding Black liberation struggles.

FREE HUEY CAMPAIGN

On October 28, 1967, Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was arrested after a traffic stop in West Oakland ended in gunfire. Oakland Police Officer John Frey was killed, another officer was wounded, and Newton himself was shot in the stomach before being taken into custody (Bloom & Martin, 2016, p. 69). Almost overnight, Newton’s case became the centerpiece of a national campaign. To his supporters, Newton was not simply facing a murder charge—he was a political prisoner, targeted for daring to demand an end to police brutality.

The Free Huey campaign began in Oakland but rapidly spread across the country. Members of the Black Panther Party used The Black Panther newspaper, rallies, and community networks to publicize Newton’s case, framing it as symbolic of the criminalization of Black resistance. The slogan “Free Huey!” appeared on buttons, posters, and murals, becoming a rallying cry for a generation of activists (Joseph, 2007, p. 162).

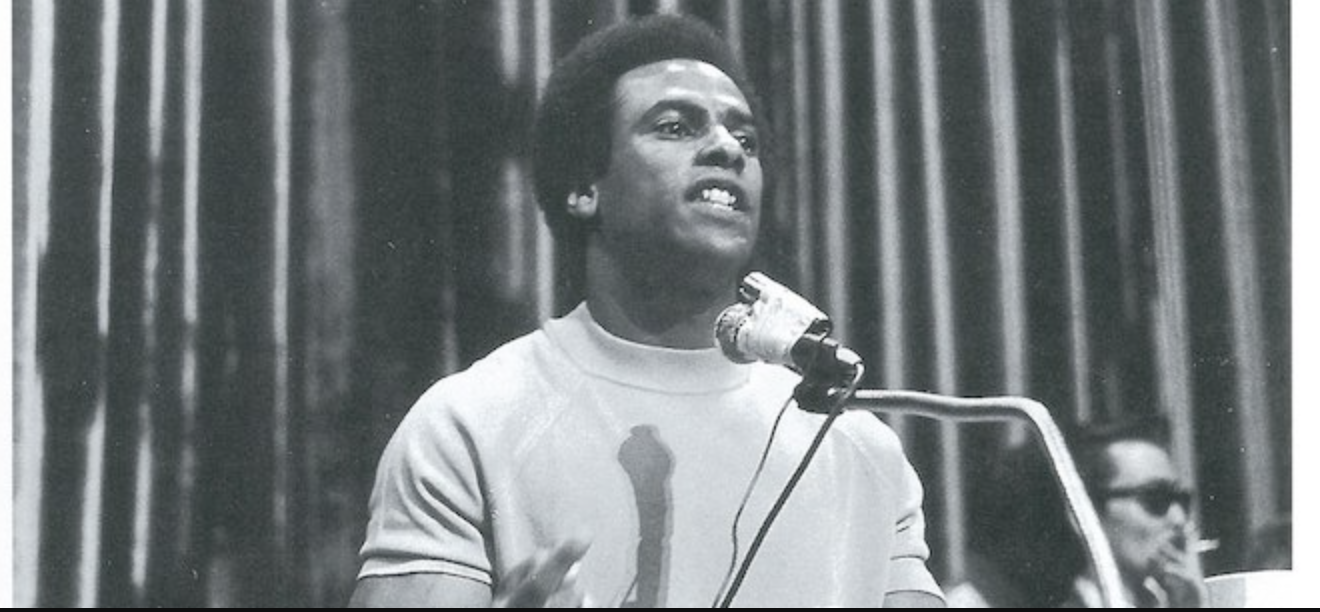

One of the most dramatic moments of the campaign came on February 17, 1968, Newton’s 26th birthday. Over 5,000 people filled the Oakland Auditorium for a rally in his honor. The event drew prominent figures of the Black freedom struggle, including Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), H. Rap Brown, and James Forman. International voices such as French writer Jean Genet, as well as celebrities like Marlon Brando, lent support, linking Newton’s case to a global fight against colonialism and racism (Bloom & Martin, 2016, pp. 78–79).

The courtroom became another battleground. In September 1968, Newton was convicted of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced to 2–15 years in prison. His supporters denounced the verdict as a miscarriage of justice. The case went through years of appeals, and in May 1970 the California Court of Appeals overturned the conviction, ruling that the judge had failed to properly instruct the jury. Newton was released later that year (Bloom & Martin, 2016, p. 100).

By then, the campaign had already transformed the Panthers from a small Oakland-based group into a national movement with dozens of chapters. It also elevated Newton into an icon of radical resistance, while making the Party a prime target of the FBI’s COINTELPRO program (Churchill & Vander Wall, 2002). The Free Huey campaign not only helped secure Newton’s release but also demonstrated the power of mass mobilization around political prisoners, setting a precedent for later movements.

Even as the Panthers would later face fragmentation and state repression, the campaign remains one of the most important episodes of the Black Power era—a moment when a courtroom battle galvanized communities across the United States to demand freedom not just for Newton, but for all oppressed people.

Sources

Bloom, J., & Martin, W. E. (2016). Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. University of California Press.

Joseph, P. E. (2007). Waiting ’Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America. Henry Holt.

Churchill, W., & Vander Wall, J. V. (2002). Agents of Repression: The FBI’s Secret Wars Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement. South End Press.

FREE HUEY

HUEY (1968)

Huey (1968), directed by Agnès Varda, is a 30-minute documentary that captures the Free Huey rally held on February 17, 1968, Newton’s 26th birthday, at the Oakland Auditorium. The event, organized by the Black Panther Party while Newton was in jail facing charges of killing a police officer, drew over 5,000 supporters. The film documents speeches by leading figures of the Black Power movement, including Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), H. Rap Brown, and James Forman, as well as solidarity messages from international allies like Jean Genet. Combining rally footage, interviews, and images of Newton, the documentary serves both as a record of the campaign to free him and as a portrait of the Panthers at the height of their visibility.

his memoir

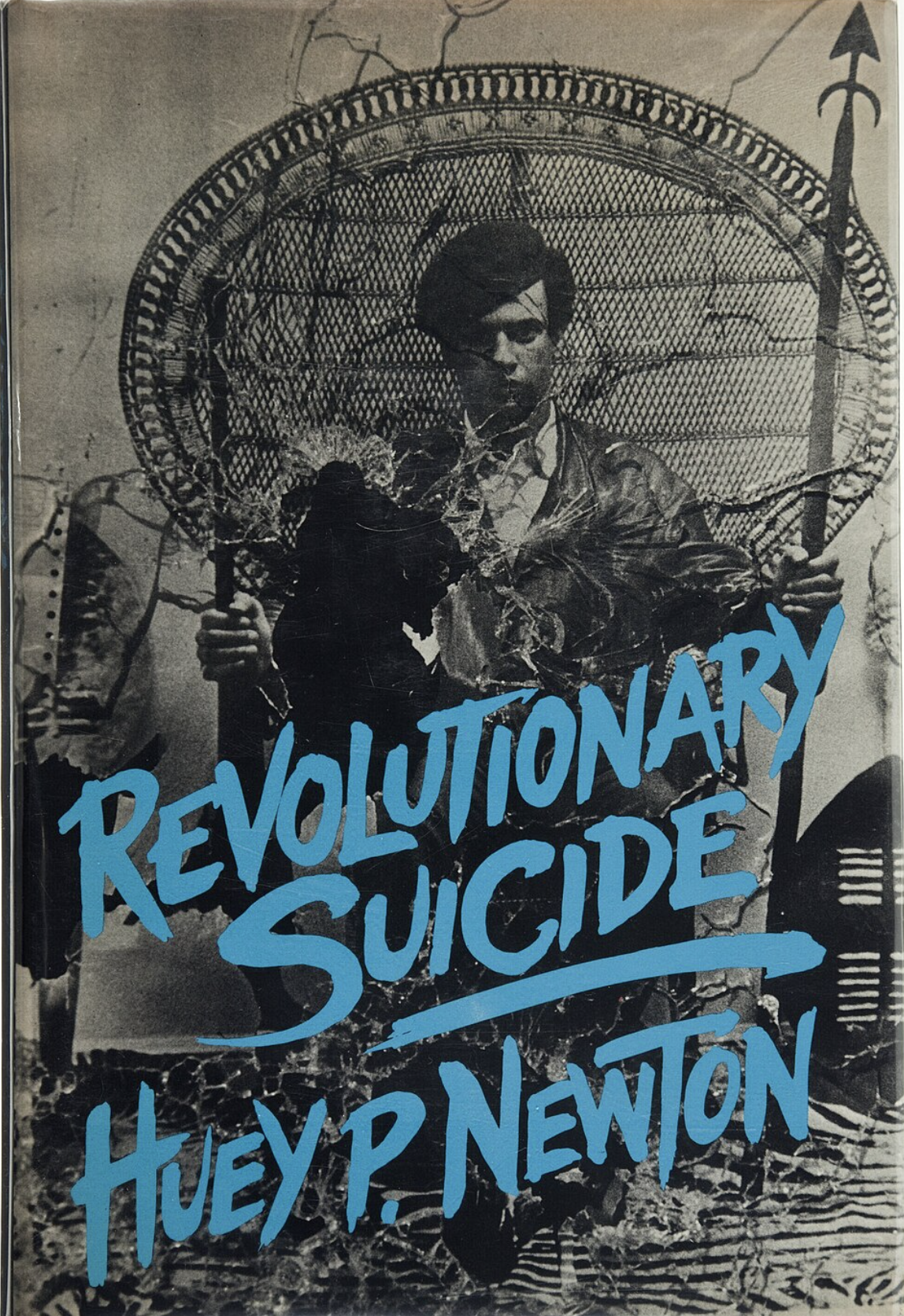

revolutionary suicide

Revolutionary Suicide is Huey P. Newton’s autobiography and political manifesto, published in 1973. Blending memoir with political philosophy, Newton recounts his childhood in Oakland, the founding of the Black Panther Party, and his experiences with imprisonment, trials, and leadership under constant state repression. The title reflects Newton’s central idea: that oppressed people, facing what he called “reactionary suicide” under racism and poverty, could instead choose “revolutionary suicide” by risking their lives in collective struggle for liberation. The book explores Newton’s influences—from Malcolm X to Mao Zedong—while emphasizing self-determination, armed resistance to police brutality, and community programs like free breakfast and health clinics. Part personal reflection, part theoretical treatise, Revolutionary Suicide remains one of the most important works to emerge from the Black Power era, capturing both the promise and peril of revolutionary politics in the United States.

learn more about huey

Maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.