JONINA ABRON-ERVIN

JoNina Marie Abron-Ervin (b. 1948) is a journalist, educator, and lifelong Black radical organizer whose work bridges the Black Power era and contemporary Black anarchism. Born in Jefferson City, Missouri, to a United Methodist minister, Abron-Ervin came of age during the turbulent 1960s. While attending Baker University in Kansas, she was radicalized by the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. That same year, she traveled to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), where she worked at a Black-owned newspaper under a repressive white-minority regime. The experience sharpened her political awareness and commitment to journalism as a tool for liberation. She graduated in 1970 with a degree in journalism and began writing for Black publications like The Cincinnati Herald and The Chicago Defender.

In 1972, Abron-Ervin earned a master’s degree in communication from Purdue University and soon after joined the Detroit chapter of the Black Panther Party (BPP). She later moved to Oakland, California, to work at the Party’s national headquarters, eventually becoming the last editor of The Black Panther newspaper. During her time in the BPP, she helped organize many of the Party’s survival programs, including the Free Breakfast for Children program, prison visitation buses, and liberation schools. She remained active in the Party until its dissolution and continued to describe herself as a Panther long afterward, emphasizing the lifelong nature of her commitment to liberation.

Alongside her activism, Abron-Ervin pursued a career in academia and Black radical publishing. From 1974 to 1990, she served as the managing editor of The Black Scholar, a leading journal of Black studies and revolutionary thought. She also taught journalism at Western Michigan University, where she mentored students and integrated radical perspectives into the classroom. After retiring from teaching in 2003, she continued to write, speak, and participate in movement work.

After her retirement, she and her husband, Black anarchist author Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin, moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where they organized in their local community near Fisk University. In response to the 2014 Ferguson uprising, they relocated to Kansas City, Missouri, and co-founded the Ida B. Wells Coalition Against Racism and Police Brutality. The coalition focused on grassroots responses to state violence, drawing from both their histories in the Black Power and anarchist movements. Although she did not attend the 2020 George Floyd protests due to the COVID-19 pandemic, she supported younger activists with political education and strategic guidance.

Between 2021 and 2023, Abron-Ervin co-hosted the Black Autonomy Podcast with Ervin, producing thirteen episodes that explored the theory and practice of Black anarchism. Today, she remains a key figure in the Black radical tradition, with decades of experience in journalism, grassroots organizing, and political education. Her life and work offer valuable lessons for understanding the long arc of Black resistance—from the height of the BPP to the present-day movements for abolition and collective liberation.

THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY NEWSPAPER

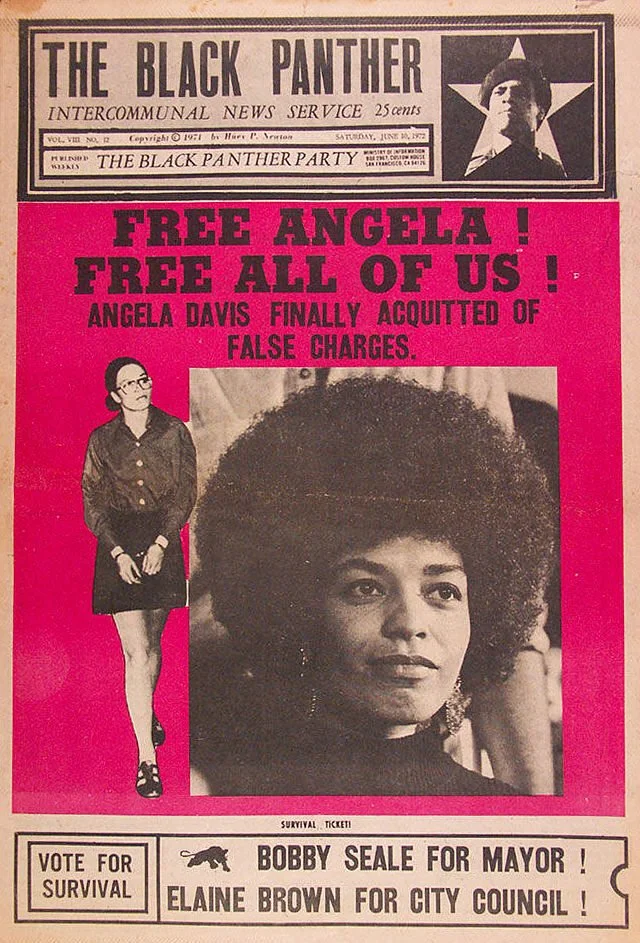

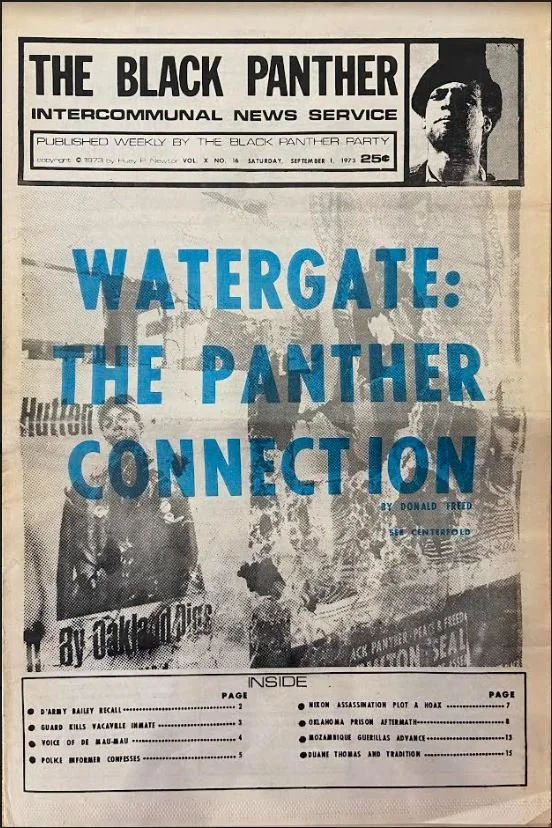

The Black Panther newspaper was the official publication of the Black Panther Party (BPP) and served as one of the most influential and widely circulated Black radical newspapers in U.S. history. First launched on April 25, 1967 in Oakland, California, it began as a modest four-page newsletter created by Party founders Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. Initially distributed by hand in the Bay Area, the paper quickly expanded to reach major cities across the country and even gained international readership. From its inception until the Party’s dissolution in 1980, over 537 issues were published, evolving from a local update sheet into a powerful organ for revolutionary consciousness and community organizing.

At its peak between 1968 and 1972, the newspaper sold over 300,000 copies per week, making it the most widely read Black newspaper in the United States at the time. The publication was sold for 25 cents and was a core part of the Party’s political education program—every Panther was required to read and study the paper before being allowed to distribute it. National and regional distribution centers were established in cities like San Francisco (the national hub), Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, and Kansas City, coordinated by a network of Party members including Andrew Austin, Sam Napier, and Ellis White.

The Black Panther newspaper served multiple purposes. It reported on the BPP’s local and national activities—such as the Free Breakfast for Children program, health clinics, and prison visitation buses—but also delivered sharp political analysis of U.S. imperialism, police brutality, racism, and economic inequality. The newspaper routinely connected local Black struggles in the United States to international liberation movements, covering revolutionary activity in places like Vietnam, Algeria, Mozambique, and Palestine. In this way, it helped frame Black liberation as part of a broader global anti-colonial and anti-capitalist struggle.

Visually, the paper was revolutionary in form as well as content. Designed by the Party’s Minister of Culture, Emory Douglas, the newspaper featured bold graphic art that highlighted police violence, state repression, and visions of collective resistance. Douglas worked closely with women artists and activists such as Gayle Asali Dickson and Joan Tarika Lewis—the first woman to join the Party—who contributed illustrations and layouts. Judy Juanita, then an undergraduate at San Francisco State, served as an editor in the late 1960s. By 1969, two-thirds of the Party’s members were women, many of whom played crucial editorial and creative roles in shaping the newspaper’s vision.

In the 1970s, especially as the Party came under increasing FBI repression and many Panthers became political prisoners, the newspaper shifted its focus toward legal defense campaigns, political prisoner advocacy, and internal party communications. Its final editor, JoNina Abron-Ervin, served in this role at the Party’s Oakland headquarters until the newspaper’s final issue was published in September 1980. Under her leadership, the publication continued its work of political education and movement-building, even as the Party itself was winding down. Today, the full archive of the Black Panther newspaper is preserved at California State University, Dominguez Hills, and select issues have been republished to commemorate the legacy of the Party’s media work.

The Black Panther newspaper was more than a publication—it was a revolutionary tool. It trained a generation in political theory, connected communities to direct action programs, and left behind a blueprint for using media as a force for liberation. In the words of Emory Douglas, the paper was “the voice of the people”—a voice that still echoes through radical publications and organizing today.