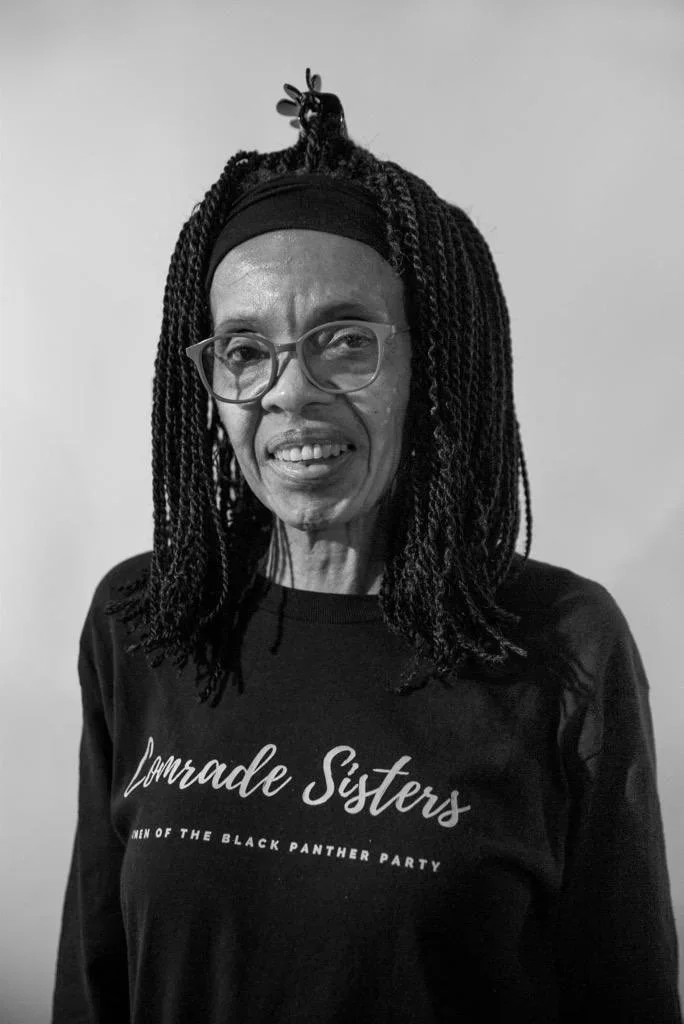

JONINA ABRON-ERVIN

JONINA ABRON-ERVIN

Listen up.

JORDAN: [00:00:00] Hey everyone. We're excited to invite you to join us on Patreon. By supporting us, you'll be helping us keep the podcast going and make it possible for us to continue sharing black radical ideas in history. On Patreon, you'll get exclusive access to reading episodes where we break down important texts, as well as early access to our guest.

Your support also helps us create more educational resources, like a website that will include educational modules about our episode, topics of potential live streams. If you wanna learn more and support the podcast, visit patreon.com/the dugout pod. Every contribution makes a difference.

Hello and welcome to the Dugout. So excited to have y'all back. We wanted to take this opportunity because we [00:01:00] have this episode in our backlog that we think needs some more love, and we're gonna republish it and it's our interview with the one and only. Joe Nina Apron, Irvin. They have a new book coming out and they also have another interview that's done video format that came out on YouTube, but that will link below.

That is inspiring and we love the archive growing with our black anarchist elders and we're so glad to be a part of that. Yeah, especially this born's history month. Let's make sure to shine the light on all the labor that is currently and has been done and will continue to be done, whether you like it or not.

Enjoy. And we're also at some new reflections at the end of this, so hold onto your seat. It's good. Re-listen. Hello. Welcome to the Doug Owl. This is an amazing episode. We got to interview Joe Nina Aron Irving. So exciting, one of my heroes. Prince, how do you feel about the episode?

PRINCE: I also feel like this was [00:02:00] really cool to do.

It felt like quite a bit more journalistic documenting history in a way. I also love the fact that it's an intergenerational conversation because I think we've talked a lot about, in various ways, like how I at least wish there were more black anarchist or radical elders that we had access to. I mean, there was one time in Cleveland where.

An old head from the Black Panther party came up to me and was like, here's my card. I'd sign up for the Black Panther party. You seem like you're down. Called them four times, sent an email, didn't get a response. So this made up for that. I feel like we covered a lot of really cool ground. We got to talk to Janina about upbringing.

It was really cool to hear about her work in the Black Panther Party and especially working on the Black Panther Party newspaper. We ended up talking about even like Jonestown a little bit, which got me on like this other research kick. How do you feel about the interview? It

JORDAN: was lovely. It was exactly what I wanted, which is I feel like there's not a lot of solo Jon Nina interviews out there and got to hear from their perspective about the Panther [00:03:00] Party, about their radicalization and about what they saw when they were traveling and coming of age.

Being able to honor and. At the same time, archive is something that I want to do with this podcast, especially knowing that there are so many folks around from freedom struggles that we're still actively learning from and unearthing the archive so we can enhance our own memory as revolutionaries, and this is one step forward, at least in our journey, and getting that project off the ground and getting that out to more folks.

PRINCE: Um, to start Jonah Aben Irvin, born in 1948 in Jefferson City, Missouri, is a renowned American journalist, professor revolutionary. She was involved in the Black Power Movement following Martin Luther King Junior's assassination, and a transformative trip to Rhodesia with a BA from Baker University and an MA from Purdue University.

Joe Nina's career included. Roles at the Cincinnati Herald at the Chicago Defender. As the final editor [00:04:00] of the Black Panther newspaper, Joanna played a significant role in organizing the party's survival programs beyond journalism. She was the managing editor of the Black Scholar and taught at Western Michigan University post-retirement.

She continues her activism, notably co-founding the Ida B. Wells Coalition Against Racism and Police Brutality. Jonah and her husband Lorenzo Kambo Irvin also contribute to the Black Autonomy Podcast advocating for black anarchism.

Um, thank you for being on the podcast today.

JORDAN: What do you feel like you could tell us about your background and your upbringing as a child coming of age and that. 1960s.

JONINA: Well, I was born in Tennessee, but I grew up in Jefferson City, Missouri. Uh, which, uh, is home to, at that time it was a, an HBCU. I don't think it's that anyway or any way.

Uh, Lincoln University and, um, where my father was a [00:05:00] teacher, uh, I grew up there with two younger sisters. Um, I was at the age of eight. I was one of the first black kids to help integrate the public schools there. This would've been back in 1956, a couple years after Brown versus Board of Education and um, uh, I didn't know anything about Brown versus Board of Education.

Obviously I was a kid, but I moved from what my parents said to me, said, well, you're gonna be going to school next year. With, uh, with white children. And for kindergarten, first and second grade that I'd been an all black segregated school. I didn't know what segregated meant, but at any rate, from the time, from third grade on, you know, I, to the school with white kids, so Jefferson City is actually the capital city of Missouri.

It's very small. It may have more than [00:06:00] 30,000 people now, but when I was growing up, it had 30,000 people and, uh. They didn't want, this was a couple years, excuse me, this was a couple years after they had the integration of the schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, and you all may have read about that and you may know that was pretty violent there.

And because Jefferson City was a capital city of Missouri, the politicians there, they did not wanna have a situation like what had happened in Little Rock. So I guess they did was they met with people in a community. Say, you know, we're gonna do this. We don't want a lot of violence. So I don't recall there, there wasn't any violence.

Uh, you know, it just happened. Um, and, um, you know, I was too young to really ask too many questions about it, but Jefferson City was a small town. Um, even though the schools were integrated, uh, the communities were very segregated. Uh, you know. Uh, [00:07:00] the black, he had his life, his cultural life, and his social life, and white people had theirs.

Um, you know, I would interact with white kids, uh, when I was at school and maybe for some extracurricular stuff, but it was pretty much, you know, like I said, integrated schools. But social life and family life and all that was still pretty much segregated when I went to college. Uh, I, um. I actually started college about the same time the Black Panther party got started, but I'll get to that later.

I went to a small, uh, church related college in Kansas Bakery University. 'cause my father and my late father, he was a Methodist pre and I got a discount going to a Methodist college. So that's where I went.

PRINCE: What did you study? Was it journalism?

JONINA: I did major in journalism at Baker University. In fact, my last two years that I was in college, I was the, uh.

Co editor of the campus [00:08:00] newspaper. So, um, you know, I got some early experience, you know, putting out a publication, which was, which was very helpful. Later on.

PRINCE: Yeah. And, and I, and I think a lot of that is interesting to me. 'cause even if I think of, uh, my family's background, my parents immigrated to the US in the late seventies and my mother mentioned, uh, moving to Cleveland, Ohio and being a part of desegregation, busing and how, um, I dunno.

I, I think about how a lot of black life is. About coming of age through history and then later on maybe having more context or more space to kind of reflect on it or give it meaning. Um, so I mean, do you think journalism and studying journalism started to give you some of those, like I guess, emotional skills to kind of realize that you were living through history or was it just kind of something that you were deeply aware of at the time as a lot of like young people kind of are?[00:09:00]

JONINA: Well, I, you know, at, at the time that I started college, the Black Power Movement was real, becoming very large across the country. And I, you know, I decided, because I started in the fall of 1966, and then a couple month, month or so after which the Black Panther Party, uh, got, you know, well, got started. You know, I hadn't heard about it, but it, it got started.

But I knew that the Black Power Movement was developing around the country. I thought, well, you know, if I'm a first, I wanted to be a lawyer, but I said, you know what, if I'm a journalist, I can write about what's going on. I can write about the black liberation stroke, and I can probably have bigger impact that way.

So that's why I decided to, to go into journalism because I figured that was a way I could contribute.

PRINCE: Okay. Um, yeah. Thank you for that. Um, and I, and I think, uh, another big flash point that I was researching about, especially in terms of your radicalization, you've talked about this before, but, [00:10:00] um, could you talk about how, um, the news of Martin Luther King's assassination kind of, kind of led to your deeper radicalization and what that moment felt like?

If you could describe it,

JONINA: Dr. King's assassination. Yeah. Well, it was, I actually was home. From college, uh, I was on, we were on spring break, so I was at home visiting my family when that happened. And, um, I was like, my thought was like, well, you know, he's assassinated. Um, he's supposed to be, talks about peaceful non-violence, yet he's assassinated.

I was very angry. Uh, very, very upset and, um. I think that that event sort of clenched it for me, that I had still had two more years of college to go, but I said, you know, as soon as I get out, I'm gonna try to get involved as quickly as I can in the black power movement because, uh, if you're going, he was called the [00:11:00] king of apostle of nonviolence, and yet somebody murdered him, assassinate him.

You know, I remember when we got back from the spring break, uh, we had a small kind of a, uh, uh, I guess, uh, some kind of a ceremony or, you know, acknowledging the fact that Dr. King had been assassinated and Baker University was a predominantly white college. There were never more than a thousand students while I was there.

And, uh, never more than out of those thousand, never more than 25 black students, at least while I was there. It might be different now. So we had this kind of, sort of observance and I remember people were just going around saying what they thought, you know, and a lot of the white students were saying how sorry they were that Dr.

King and killed. So, uh, you know, I said, well, you know, um, white people are responsible for this. Uh, black people didn't assassinate Dr. King. And, uh, you know, which was kind of this, uh, strange [00:12:00] statement for me to make. I was not your necessarily your angry type of young person, but I was angry. I said, I said, you know why people, you all are responsible for this.

So, uh, and it did, like I say, it really solidified in my mind that I was gonna become a part of the Black Power Movement as soon as I could. University was a, as I says, is a Methodist that was, was founded by the Methodist church, was a Methodist institution. And what happened was they were in contacts.

This was uh, the summer of 1968. It was really very eventful 'cause Dr. King had just been assassinated. And I think days before we left, Bobby Kennedy was assassinated. Baker University had ties to the Methodist Church. We had been invited by the Methodist Church there to have some kind of a summer program for students.

So, um, you know, I had never been out of the country and I talked to my parents about it. They thought, well, this is, you know, I got them to agree to it that it would be a really good thing for me to do. So there were about, what, eight of us, six or eight of us. So I was the only black student in the group who went and there were some faculty [00:13:00] members and then some other people who were close to the university who went.

So for me, I was excited because as a, a black person, I had never been out of the country, let alone going to the African college. So I was really excited about this. I had some, obviously some misunderstandings. I thought that, you know, African countries predominant population were black people, that they were in charge.

I was not educated at all, really what was going on in Africa. When I got to, at that time it was called Rhodesia. Now it's Zimbabwe. But when I got to Rhodesia, Zimbabwe, I found out that black people were not in charge. Of that country and that, in fact at that time they were engaged in an armed liberation struggle with the white, uh, colonial, as they called it, set regime.

The armed struggle was going on at that time that we were there. So I learned a lot that summer really made me grow up and really begin to understand the world, uh, and really shook up my understanding of the world. And I [00:14:00] began to understand that much of Africa was still under white colonial rule, and I hadn't had no knowledge of that before.

I was, you know, gaining an international understanding. I, I had no experience being overseas. See, this was, what, 1968? So the late sixties, you had a lot of armed liberation struggles that were going on, on the continent of Africa. And I would hear about them, you know, in the news. I remember very well, uh, Patrice Mungo was assassinated because my parents would always watch the news and I would watch too.

And I didn't fully understand what had happened. But when I got to. Prodi, Zimbabwe, everything started to click I, I've started to really get an understanding what was going on in the world and understanding European colonialism. So it was really quite an educational summer for me. I worked, the newspaper that I worked on was a newspaper actually published by the United Methodist Church.

I lived on a, a mission of the United Methodist Church. That's where I lived. I was [00:15:00] living with a young white American missionary. She was actually had dual citizenship because her parents were missionaries. Uh, she was more actually being in Rhodesia, so she was spoke American and Rhodesian. I lived there with her, and so I lived on this mission.

It was very interesting because the black people there had not ever met a Black American, so they asked me to come and speak to them one day. You know, there were all, you know, protests were going on in the United States with Black Power Movement was very active. So one person asked me, he said, well, we don't understand why black people in America are.

Protesting so much because, uh, we read Ebony magazine. We see that and black people have a seem to have lots of money and are doing really well, and are really rich. And I thought to said, wow. I said, I didn't say to them, but I realize how misinformed that they, they were getting the wrong view. So I said, well, you have to understand that many black people in America don't live like the black people in Ebony Magazine.

They're poor, they don't have jobs. They live in poor housing. Getting that question [00:16:00] was like really educational for me. I don't know how much I helped them. It's like, wow, they don't really understand what's going on. And of course they didn't live there and they're only getting one side of it. If you're just looking at it from the point of Ebony and Jet Magazine, well, what are you gonna think?

It was very, very educational for me. I, I would say that was a key stage for me, you know, ultimately leading to the life I lived after that. Just understanding that being there and seeing what was going on.

JORDAN: Were you dealing with having to do with any like censorship and repression with the journal in Radio Justice?

JONINA: Yes, it was put out by the United Methodist Church, but if there was anything in the newspaper that the government didn't think people should see, they censored it. So, you know, I wrote some articles for the paper and helped with some of the proofreading, but I remember the first issue I saw after I got there, it was this issue.

It had all these. Pages that were just blank, that were just white, and I'm like, wow. And the editor explained [00:17:00] to me what that was. Well, this is censorship. The government censors what they don't want people to see. I'd never seen anything like that. That again, was part of my education to actually see

PRINCE: firsthand.

They would go to the printing press and just remove entire pages or like at what point did they censor it?

JONINA: If my memory is correct, they had to actually send the, what we call back then, the dummy, the layout, whatever, to some kind of government official for them to approve or not approve. And so if they didn't approve of it, they would just themselves just wipe out that page or that article, or had never seen anything like that.

You know? And I was really young if that, not long after we got to Zimbabwe, I celebrated my 20th birthday. So here I am, this 20-year-old black kid who you know. Fairly sheltered. Being a preacher's kid coming into contact with all this stuff. It was really, really something.

PRINCE: I guess this is kind of a question that I am sort of curious about now, hearing more about Rhodesia and I'm even just thinking about some of my experiences traveling, sort of similar to [00:18:00] you, like after college, I graduated in 2015 and in 2016 it was the presidential election, and I remember around that time I went to the Philippines and around that time Rodrigo Duterte was president in the Philippines.

Extra big on war on drugs, a lot of extrajudicial killings. And so I kind of went there with my own context of the war on drugs in the US and people there kept saying, oh, like do you play basketball? Or what is it? Like, I don't know. Like same, same things like you. They were like, oh, we watch music videos and we watch YouTube.

And it was interesting 'cause at the same time, people. Also in the Philippines would be like, oh, how do you feel about Trump? And I was surprised, one, the limited idea of blackness that they had, but two, also that they felt like the danger of Trump made sense to them or was like something that they could bring up.

And I, I just find that like fascinating and I, and I guess I just wanted to bring that up, but I know after Rhodesia you ended up joining the Black Panther Party around, what was it, 1972.

JONINA: Yeah, 1972, I I did take time. I graduated from [00:19:00] college and I did take time to go to grad school, but I did join the, um, black Panther Party in 1972 in Detroit.

I actually joined the second chapter of the Black Panther Party. The first chapter of the party was infiltrated by counter by Coen, the FBI counterintelligence program. They placed a provocateur in the ranks. Who got some members to go to this house. They were supposed to be, you know, trying to deal with drug dealers.

Uh, but they wound up killing, uh, a young man in the house and they wound up being charged with, you know, his death. And this really discredited the Black Panther party in the black community. The, uh, leadership of the Black Panther party closed the chapter of the Black Panther Party at that time, when that happened and what was going on by 1972.

They had given permission for the chapter to be reopened. So yeah, I joined the second chapter of the Black Panther Party in the summer of 1972. We ultimately went to Oakland in 19, uh, 70, early 1974. The [00:20:00] party was trying to consolidate all this chapters to Oakland because they wanted to make Oakland the base of operations.

So they closed a lot of the chapters, and so a lot of us, you know, moved to Oakland.

PRINCE: Was that around the time that I think it was? Was Elaine Brown doing a lot of work like in California or I, I can't remember who was doing a lot of like housing work there as well.

JONINA: Well, she had, the year before, Bobby Seale had won for Mayor of Oakland in 73 and Elaine had won for Oakland City Council.

I wasn't there for the campaign, but they did, they lost the campaign, but the party was beginning to, to broaden out, you know, in terms of the kind of, the kind of stuff that we were doing. They were trying to broaden out and bring people from different chapters they felt helped. And they also were trying to bring, not long after I got to Oakland, Huey Newton went into exile in Cuba.

We got there and I guess. February, March of 74 from Detroit and then, uh, Huey, uh, willing to exile, I think August or September of 74, and the party was trying to bring Huey back from [00:21:00] Cuba. That was the goal, to be able to have an environment that would be conducive for him to come back to Oakland. 'cause he faced serious criminal charges.

One of them was murder. So the party at that point began to get more involved in electoral politics because they wanted to help elect a mayor that they thought would provide a more conducive atmosphere for Huey to come back. So they got involved in the uh, campaign of Lionel Wilson who was running for mayor, and he was subsequently elected.

As mayor, the party put a lot of resources and tied into campaigning for Lionel Wilson, and he was elected so that by the July of 77, Huey was able to come back from, he did come back from Cuba

JORDAN: with the party. You were one of the last editors of the Black Panther Party newspaper. Can you talk about that experience and what was the paper's purpose at the time?

JONINA: I started working on the paper. Not long after I got there in 74, but by the time I became editor in 1978, the party had lost a lot of membership. It had gone from being a weekly [00:22:00] newspaper to a bi-weekly coming out twice a month instead of every week, and that ultimately, it became a monthly publication because the party did not have the people anymore, did not have the financial resources to put it out as frequently, frequently as it had been.

You know, we still did our best to, to, to put out a, a good publication. One of the major issues that I I, I helped to put out when I was editor was the issue that we did about the Jonestown Massacre. We did an issue on that because we knew people who were in Jonestown. Uh, you know, we felt like Jonestown people had left San Francisco, that People's Temple was based in San Francisco and they had left San Francisco to go to Guyana to start.

Jonestown and we felt that this was an indictment on American society because these were mostly poor people, people of color. You were saying that we can't live well in the United States, so we're gonna leave the United States, go someplace else and, and start a society. We knew them. Their attorney, uh, was Charles Gary.

Charles Gary was the [00:23:00] main attorney for the Black Panther Party. So in fact, I knew one young woman pretty well.

PRINCE: Is it true that Huey Newton had a cousin that was in Jonestown as well?

JONINA: You know, it could have been possible.

PRINCE: I've researched a few times and I, I think I remember his name being Stanley Clayton.

'cause that was like something I really started trying to understand a few years ago, like how the Black Panther party new folks in Jonestown and vice versa.

JONINA: One of the reasons that could have been, I don't recall that about, I'm not saying it's not true, I just don't recall it. That could very well have been, like I said, because we had the same attorneys and because, you know, people simple.

Did the community work in the black community in San Francisco? That was, you know, similar to the kind of things that we did, we felt a connection to them. So we did this issue on what had happened in People's Temple and uh, we did a lot of research on it. We found out that at 1.1 of the people who had been at People's Temple, who may have been an advisor to Jim Jones, had at one point been in the CIA.

And so we just, you know, kind of dug up a lot of stuff about what had happened in [00:24:00] Jonestown. And so when we finally put our issue out that people simply was, had been deliberately undermined by the US government. Uh, that was our point of view, because it was making a statement about conditions of poverty in the United States.

There was a congressional investigation. Because there had been reports of violence going on in Jonestown, so there had been in, in the investigation, and of course a congressman, uh, was killed there back in 78, and that's what brought all this public attention. Then of course, all these dead bodies of almost 900 people were found to make a long story short.

We came up with the position at the time that was very unusual. Our position was, was that people's temple had been destroyed by a, I don't know whether it had, they still call it this or not, a neutron bomb, which a neutron bomb leaves, no signs of anything about how it was set off or anything. Since that time, I don't believe that anymore, but that was our opposition, that it had been deliberately destroyed by the government, by a neutron bomb because [00:25:00] it showed the poverty and all the problems that black people had in the United States, and it let the United States to come to People's Temple.

That was our last major big investigative issue that we did. I still believe that there was some government interference in people's temple. I necessarily believe it was a neutron bomb. We may never know exactly what happened, but I believe that the government did not want to see people's temples succeed.

And then of course, there's all the issues about Jen Jones and everything. We may never know the full truth about what happened there, but it was definitely a tragedy. All those people, all those people died.

JORDAN: What do you feel like people miss when they engage with the Black Panther party now? Like would you say that there's a contemporary romanticism of the party, uh, leaders and things, or how do you feel the discourse is going?

I

JONINA: think there is, there has been a romanticism. You know, I always tell first when I'm talking to young people like. I tell people, you know, you can't recreate the Black Panther Party. It was founded in [00:26:00] 1966. We had a specific set of socioeconomic political conditions going on in America. We don't have that right now.

We haven't had it since. You can't take it out of context. And put it in another time era. I respect the fact that people still respect the Black Panther party and admire what they did, and I'm glad that they do, but you can't recreate it. And there has been a lot of romanticism and that. I see a lot of that continuing on.

We used to talk about concrete conditions, and you have to deal with the concrete conditions of the era that you are in right now. For instance, one of the reasons that Huey and Bobby started the party was because of the problem of police brutality in the black community in Oakland. Well, police brutality in the United States.

Right now it's. Far worse than it was back then. I mean, it was bad then, but it is far worse. You don't need me to tell you what you see every day. Black people are just being killed every day. The woman in, in Illinois who was killed black, pregnant woman who was killed last year, the numbers of [00:27:00] black people being killed by the police has gone up exponentially since 1966.

Right? So the conditions that we have in this country are far worse. Economic conditions. There were homeless people you know, in the United States in 1966. But it's far worse today, much worse than it was back in 1966. So this is a reason why I always try to tell young people that you can't remove the Black Panther Party from what it was doing, from the socioeconomic, political conditions of the talk.

You have to deal with what is going on in the country today, and you have to decide, do we need another, another Black Panther party, or do we need something else because our conditions are worse than they were.

PRINCE: I really appreciate you saying that because it's something I think about a lot. I just turned 30 this year, and even in my lifetime I can kind of see how now in movement work, I'm meeting people that are younger than me or have been radicalized more recently.

We were actually watching some of your interviews earlier and we watched a, an interview you did with Angela [00:28:00] Davis, and you kind of both made a similar point then about how there's a. A set number of sociopolitical conditions that led to this mass mobilization and how there is always a desire for a new kind of mass mobilization.

And maybe this is like a large question, um, but looking at the landscape today, like what advice. Would you have for younger organizers or people that might be looking for wisdom? Um, and I know some of that is like constant experimentation and, and trying, but I guess I wonder what advice would you offer to folks that are coming up in movement work now, especially like with social media and all the varying levels of repression that people are facing and election years, things like that.

JONINA: I would encourage or ask young people, millennials, gen Z, you know. To look at what is going on in the country. I know you all have been dealing with the elections in recent episodes to to deal with the reality that right now we are facing the possibility of a fascist [00:29:00] dictatorship in America, project 2025, and the Supreme Court has said that presidents are are immune from acts that they took from that they were in office right then.

We have the project 2025 that wants to make the office of the president all powerful Congress and the courts lose a great deal of their power. I would like people to take a look at the, at the reality that we could be facing it. Obviously, I don't know how the elections are going to turn out. We just have to wait until November, but we are facing that and even without whether Trump or you know, or Harris wins.

Fascism is on the rise in this country and it's gone beyond, you know, just groups like the Proud Boys and all that. This is very entrenched in governments right now. You have governments, state governments who are enact all this censorship hooks that are being censored. You have voting rights that are being decreased.

To me, this is Rise of Fascism. I'm not a genius. I can't tell people exactly what to do, but one of the things we need to be prepared for is [00:30:00] what will we do if Trump does win? And if in fact, project 2025 is enacted, I mean, if he wins, he claims he doesn't have anything to do with it, but you know, that's a lie.

He's just trying to distance his from it because he knows a lot of people, even a lot of Republicans don't like it. What if he does win? Are we prepared for what may happen? You know, if he does the president becoming all powerful things like, uh, they want to do away with, say, the Department of Education because they wanna destroy public education.

And a lot of states, they've already started moving to destroy public education. The governor of Tennessee, where I live, wants to have all these vouchers for people to be able to send their child to any school. They want to, 'cause they're trying to destroy public education in the state of Tennessee, but that's not the only state.

So how are we respond to that? How do we respond to the fact that maybe if you go to the polls on election day, you live in a state where they have open carry [00:31:00] gun laws, they validate you when you try to vote. We're gonna have to be prepared to defend ourselves, not only with the arms, we do have the black people, unless they change the law instead, oh, this only applies to white people that, uh, seek to decrease our power.

You know, they don't wanna teach black history. We have to be prepared for that. And I'm not trying to scare people. I just think we need to be realistic. We need to ask ourselves what are we going to do If in fact, Trump does get reelect and Project 2025 becomes they, they start working on it. They start moving on it.

We need to be, begin to develop a, a movement against fascism. A lot of people don't know, but the Black Panther Party in 1969 organized a national conference, United front against fascism. Are you all familiar with that? Yeah. Have you heard about that? I haven't

JORDAN: read about I, yeah, about that. I've read about it.

It was like a really big coalition. Got a lot of folks together and it really showed like, like a succinct, anti-oppression, unity based thing. I wouldn't say I've read that much into it, just that I knew it [00:32:00] happened. Because it inspired a conference here in Columbus in the nineties, and they were like, we're trying to be in this image.

PRINCE: Mm,

JONINA: yeah. They did that in 1969. A lot. They don't get a lot of credit for that. That was in 1969. People came from all around the country, but by 1969, you know, black Panther party was under severe attack by the counterintelligence program itself. The conference may have been held at a point when the party was.

So under attack that it wasn't really able to follow up on what they were trying to do, uh, after the conference. And one of the things the party was criticized for, what the conference was, was that it had far more white people came and black people came. And this is not to say that we don't unite with white people who are concerned about fascism, but at that point in time we were black people.

Were sort of, you know, getting the brunt of all this. We need to look at organizing some kind of a, a movement in this country right now that can face fascism in the 21st century. Late 20th century, the Black Panther, the party did that. Now, now we're into [00:33:00] the first, you know, 25 years almost of the 21st century.

So how to fight this rise of fascism, you know, that's the way I see it. Many people think, well, you know, Trump's just mouthing off and even if he gets elected, he's not gonna do all this stuff. Well, you know, I don't, I don't take that for granted. If people say they're gonna do something, I think you need to pay, pay attention to it.

Okay. Like I said, I don't have all the answers, but one thing I do strongly believe is that we must begin to build a movement for fighting fascism. And I'm not saying it has to be all black people. We have to unite with people of different racist nationalities has to be widespread, broad movement. But we have to begin to do that because fascism is on the rise in this country.

And if we don't believe it, when we do finally believe it, this is gonna be maybe too late.

JORDAN: Because whoever wins in this election project 2025 is gonna start training people. 'cause that's their whole goal is, is like half of it's a training and educational platform to train [00:34:00] folks to be better fascists and to unite around the cause and have the same, I don't wanna say brain worms, it seems mean, but yeah.

JONINA: For a lot of individual states are already enacting things like Project 2025, so to me this whole kind of neofascist thing that's been going on in the country has already been going on in a lot of different states. And Tennessee may have the, the greatest number of laws anti L-G-B-T-Q laws. In the country in May.

I read that someplace, I don't know where, how extensive their research is. There's that, and there's the whole thing with the schools tax on voting rights. Even if Trump doesn't win, you still got all these things going on in individual states. You know, people who are organizing need to start looking at what is going on in their states in terms of the rise of fascism in in their cities and towns.

What is going on?

PRINCE: I appreciate you saying that because the last year alone for me on an organizing level has been a lot like seeing the series of ongoing genocide, seeing the, uh, student encampment protests kind of crop up, [00:35:00] and at least for me and other folks here locally, that was kind of the flashpoint.

And I guess I wonder how you think of solidarity work when you're trying to do organizing and solidarity work with people that might be more fearful of repression or might. Work with the state more. How do you view solidarity work when it's across those lines of how people feel about state repression, how soon they might fold to it?

Because I can say locally there was a lot of difficulty with organizers. Some folks didn't wanna talk or work with the police at all, and then there were other people that were a lot more fearful and would hand information over. But in your experience, like how do you navigate that space?

JONINA: I wish I was smart enough to be able to give you a concrete, solid answer.

It's very difficult. It's situation by situation, case by case, okay? What may work in Cleveland is not gonna work here in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and it's not gonna work in Oakland, California. You have to look at what is going on in your community, but I do understand what you are [00:36:00] saying, man, to a situation like that here in Chattanooga, about a year ago when the young Chicano.

Teenager was killed by the police and, um, felt like, you know, we need to go ahead and have some serious street protests on this and really raise the issue. But, uh, there were some people in the, uh, you know, Chicano community who were, um, the Latinx community who were afraid of repression that I underst.

They're afraid of being deported. And I, not, none that I understand it, it's very difficult to work through that extremely, just have to take it case by case and do what you can do. You know, in terms of, uh, for myself as being an, an elder in the struggle, uh, that kind of solidarity work that I try to do, I focus on is doing things like this, talking to younger people.

Like yourselves trying to pass on information because you are in the situations that you're in and you are doing what you're doing. I'm not, I can't, I can't be in your shoes. And because I'm 76 years old. You, you're, you said you were 30 years old. Well, I haven't seen that in 46 years. I can't [00:37:00] presume to tell you exactly what to do and how to do it.

What I could do is tell you what I experienced in the past, what I have seen in the struggles that I went through during the, the seventies and on, on up until now, and give you information that may help you as you go along. As an elder, you know, I'm a revolutionary elder, but I, I am still an el elder and I have to be honest about that.

Realize that I cannot tell, give you orders. So you, you all need to do it like this. Do it like we did it back 30 years ago or 40 years ago. Well, you can't do it like we did 'cause things are different. I mean, you know, the reality of it is if we had had. Cell phone and if we'd had the internet, we might've been able to fight the FBI counterintelligence program.

We might've been able to, you know, wage a bigger struggle, you know, 'cause we could've been in quicker contact with each other, but we didn't have that. That's main thing I guess I wanna say, say to that is, is that for me, on a personal level, solidarity is I try to talk to young people as much as I can.

When they ask me, they ask my opinions because I feel like [00:38:00] it's my responsibility as a revolutionary elder to pass on information. 'cause you know, we're not gonna be here forever. No one is, and gotta pass the information on. One of the people that I interviewed many years ago who was a black power era activist like myself, and she said one of the things she thought that we, we were missing, she said, you know, we don't have a library.

She said, but the young people to go to. To be able to know exactly what we did and how, why we did it and how it's one of the reasons that I initially did those interviews to bring that out. 'cause there are lessons that can be learned and I am in, in the process of updating that book and ex doing an expanded version on it.

Yes. Love it. So. It'll come out next year. That information is needed, so, so you can take from the, what you can use when you think can work for you or you can take from like, wow, they did that back then and now it's much harder to do stuff like that now. Or how do we do that now? That's how I feel about, feel about that now.

PRINCE: Yeah. Thank you for that honest answer and I feel like that's, I really appreciate it. First, just wanted to [00:39:00] say thank you so much for taking out your time and talking to us. Like I am really humbled to. I get to share space with you and to hear your thoughts and your perspectives, so thank you. Thank you so much.

JORDAN: Thank you so much and can't wait to see what more is going on and hopefully we can have more conversations.

JONINA: Well, thank you so much for giving me the opportunity to be on your program and to reach more people. Uh, I'm always glad to do the, happy to do that. Um, and I appreciate you. I, I feel appreciate you asking.

Thank you so much. Love and struggle.

JORDAN: I think there's a lot of things. That I've been thinking about since we first did this interview, like what are the dynamics around censorship that we are dealing with and we'll have to deal with in certain ways. I think about during prisoner solidarity work and how getting essays from people sometimes feels like reading TikTok captions when people replace all the different letters so they don't get screened by whatever censorship program they have going on.

And when Joan would talk about. [00:40:00] How pages would be taking out, and you didn't even know. I think about the shadow bans and how, if you look at even more authoritarian countries that are active in their war of aggression and attrition against their citizens, the internet shutdowns that happen, um, lots of folks have been thinking, especially with Elon being so connected to the federal government about the impact of Twitter and like the ownership of communication distribution and how that is key.

Key for popular education and fighting misinformation and all the kinds of censorship that the state is already enacting. Joanna talked a lot about what if Trump, and even if not Trump, the rise of fascism in this country, and it's here. The people are disappearing and the support groups are necessary.

And I think about all the culture work and community building and grassroots efforts that is inherently anti-fascist. And especially when added to this revolutionary political agenda that the [00:41:00] Black Panther party was moving with, um, and the anti-fascist coalitions that they were trying to build and were building.

That's the kind of power that. I think we need to be addressing.

PRINCE: What lessons do you feel like black folks should be taking away right now in terms of thinking about anti-fascism? I guess I'm curious what you think about this because of what's happened in Columbus, Ohio recently, and Lincoln Heights, Ohio.

So I guess what's been going through your head in relation to how. You're thinking about it, how you think other folks should be thinking about it.

JORDAN: We have to fight the go fight, but also realize that we're not doing it alone and we're not the only ones impacted by this. I just saw like videos on tiktoks, like of immigrants, visibly Hispanic, lucky immigrants getting spit on and a Walmart.

By a nigga, by a black dude. And then they got into a physical altercation and where the dude almost got shot. And it would've been pretty much just a lynching because people just kind of just stand there and watch. Um, and thinking about whose bodies have been [00:42:00] lynched in this country. And that's indigenous folks, and that's Mexican folks, and that's black folks.

And we're all fighting this white supremacy and making room and space for diverse stories against this repression and also holding each other in. All of our different vulnerabilities and all of our different states of mind is the only way. I see to get through this in one piece, and that's with the idealism of coming out in one piece.

But I think it's possible, and I think that I'm not gonna look at the past and say, we did it, and we can survive it. Because they're gonna look at that past and say, Hey, how can we exterminate them harder? So we have to learn how to protect ourselves harder. Faster, stronger, more sustainably with all the loving care.

It means harder, faster, stronger. Yeah. Listen to Kanye, if you wanna be anti-fascist. That's historically the number one biggest anti-fascist right now. What are some things that you think about from this interview or things that linger from your mind? You know that it's [00:43:00] been five months since we did it.

PRINCE: I think the censorship is a big thing, especially now that we're deeper into working on the dugout, and I feel like we have ideas and plans, and I'm glad that we have been developing this platform or this space because it does feel important to be an example of how people can practice. Looking at the news, having conversations being critical, and also competiting disinformation, I think is a big thing in relation to what you were saying about fascism and how.

People of color, black folks can also be initiators of it. And I think the fighting disinformation part is really big. And then I also think both understanding history and kind of to Jonah's points, realizing that we're in a new context. Like of course there's things we could tap into, learn from, things from, but the fact that they're.

People in the government are using Signal and somehow, I don't know, it's just, I just really keep thinking it's both time to evaluate, make plans, think long term, but also like take the time to understand what is happening. Take the time [00:44:00] to figure out your own framework or approach, so when those vital conversations happen, you're just not.

Like caught off guard. People just really need to be talking to each other and be real about the things that are happening, how it's affecting them. It is strange to listen back to something and be like, wow, that was before this new iteration of our hellscape began. And it's not like I look at this interview and I'm like, that was fonder times.

I don't know. 30% of me feels that way.

JORDAN: Yeah. Re-listening to this for the re-upload. I am just thinking about having more of our elders on again and having that be something more consistent. And it's not just about the one time interview, like even with Janina and Jamal and wanna get Austen on and all these other folks that really inspire us and have a lot of wisdom.

The introductory interview is amazing, but I really wanna get into the nitty gritty of what's going on in their heads. Um, some things that I [00:45:00] wish I talked about more with Jonah was about the education and curriculum about some of the day-to-day for the newspaper. Um. The different ways that they handle distribution, the different ways that like, just yeah, some of the nitty gritty things where I'm like, I'm sure it's somewhere, but I want to, I wanna hear it from someone who had to work through the kinks with it or came into the process with things in a certain way.

Uh, what are some things you wish you talked about with Joanna?

PRINCE: In a way I keep thinking about the latter end of the conversation where I was kind of like, what advice would you have to younger people? It's not like I would've turned around and been like, but give us advice. Maybe to your point, just interested in even more about Jonah's analysis of what is happening, how it maybe feels different than the past.

Um, 'cause I am interested in that space even now with this second Trump presidency. Part of me is looking back at the first one, or even when I was in college, and it's not like I. I wanna say I have a nostalgia, but I do feel [00:46:00] like things feel very different now, even if it is only four years later. And so I wonder what that feeling is like for folks that have been through years and years of movement, um, and seeing people in and outta jail and yeah, I'm just interested in what.

That feels like in how folks process that as you get older and older. So I, I don't know, maybe it's more emotional questions. Yeah. But I still really love this interview. And I hope people enjoy it. And for any folks that are following the podcast, if you really want to support us, of course, check us out on Patreon.

But, uh, we're trying to expand into different platforms. We're on Mastodon. And then if you also want to sign up for our letterbox, um, the dugout has a letter box now, and if you go into the description of this video or you go onto our link tree, our bio site, um, you can find a hole. List of [00:47:00] thousands of movies that explore anarchism or explore some aspect of anarchism in some way.

And it's definitely an intention for me on this podcast to Dick more into media, talk more about film. And we do have a episode coming down the line where we review both, um, a Panther film that was made in the 1990s that had Angela Bassett in it actually. And then. Also, um, the Apple TV series that came out in 2024, the Big Cigar, so stay tuned for that.

Any other things down the pipeline that you want listeners to know? Any messages for listeners

JORDAN: after this episode for the next three weeks, maybe even four bang or bang or interviews, and you're just gonna have to be surprised on who they are. And any message of advice, organize a support committee for yourself, for your friends.

Take that shit seriously. Take your mental and physical health seriously. Hold space to be vulnerable, even just to yourself. Not gonna get outta this [00:48:00] alone. You didn't get into this alone, even though you can feel

PRINCE: lonely. Love and struggle. And remember, everyone, every month is Black History Month unless you're racist.