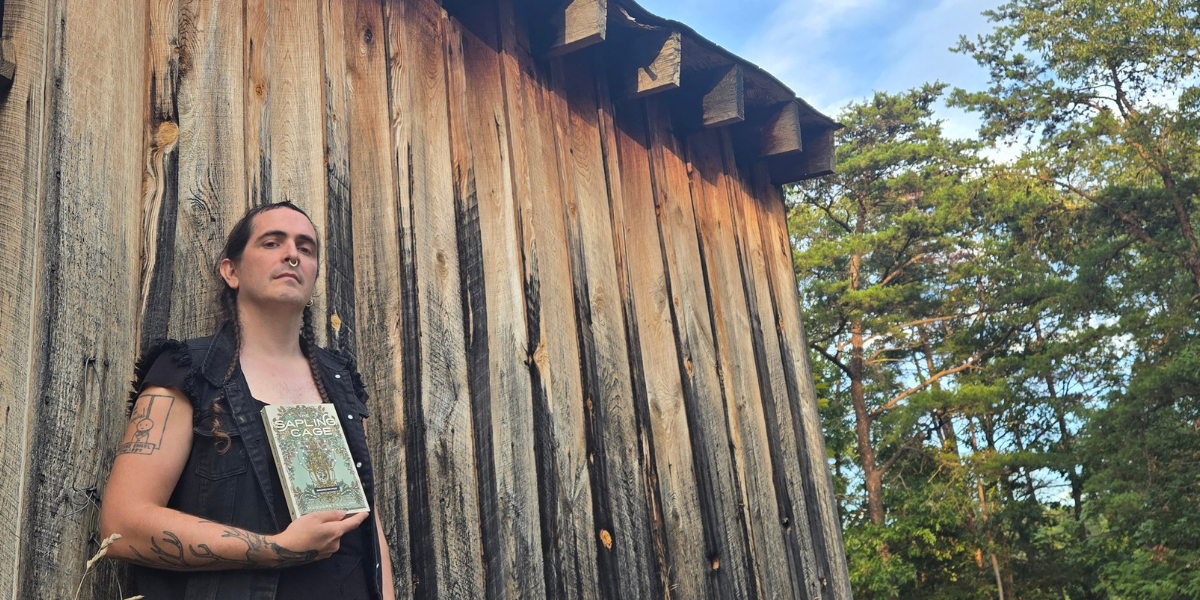

MARGARET KILLJOY

Listen Up

In this episode of The Dugout, we’re thrilled to welcome Margaret Killjoy, a prolific author, musician, crafter, and unapologetic anarchist. Margaret shares her journey from growing up as a "confused goth kid" in the suburbs to discovering anarchism through punk subculture and anti-globalization movements. We dive into the role of speculative fiction as a medium for radical imagination and discuss the intersections of identity, politics, and art. From DIY zines to the lasting influence of Steampunk Magazine, Margaret reflects on her experiences building and engaging with anarchist communities.

BUY SOME OF MARGARET'S BOOKS... [AFFILIATE LINKS]

📚 If you want to read their new book Sapling Cage you can buy it here - https://bookshop.org/a/109212/9781558613317

and here are some links to our favorites📚A Country of Ghosts - https://bookshop.org/a/109212/9781849354486

📚 Escape from Incel Island! - https://bookshop.org/a/109212/9781958911020

📚 The Lamb Will Slaughter the Lion -https://bookshop.org/a/109212/9780765397362

📚 We Won't Be Here Tomorrow: And Other Stories -https://bookshop.org/a/109212/9781958911020

JORDAN: [00:00:00] Hello and welcome to the dugout. This episode we have an amazing guest. Author, musician, crafter, general Jack of all trades, Margaret Killjoy. I'm really excited to get into this conversation and share this with y'all. I think there's wonderful bits of knowledge from their experience as a seasoned anarchist observer of history, and I think Margaret Killjoy.

Is doing a lot to keep us educated, and we have a lot to do with that information. But a little bit about Margaret before we get in. She spent most of her career and adult life on the road, currently nestled in the Appalachian Mountains politically. She's an anarchist and believes that society would be better off without systems of hierarchy and oppression.

Just like us, it doesn't really fuck with state [00:01:00] capitalism, white supremacy, patriarchy, and the like. And if you like this interview and you want to get some of ours early or get some exclusives readings or some of the readings early, you can head over to the Patreon at patreon.com/the Dugout Pod and we'll have some stuff to come for you.

Very excited for next. Month, black years, two month is gonna be hitting y'all. Stay safe, stay dangerous. Sam, I hope you enjoy this.

PRINCE: First question I'd like to kind of ask guests is, what was young Margaret like? Where did you grow up? Could you tell us about your younger years?

MARGARET: Lord. I was a confused kid. I didn't know I was a girl. I didn't know I was an anarchist. I just lived in the suburbs. I don't really wanna kind of exactly say where, when I watch movies about suburban life in America, that like wasn't my experience of life.

It wasn't an upper [00:02:00] middle class suburb, and I feel like that's like all that's represented in media or whatever. Right. Rode my bike around and did drugs and shoplifted and technically graduated high school and just kind of confused and I wanted the world to be weirder and more interesting.

Piercing and body mod type stuff and I was a like little weird goth kid. I actually had a pretty like strong clique of, of weirdos in high school. Born in the eighties. I grew up in the nineties. It's now long enough ago. I know this sounds cliche, but it's like long enough ago now that there's like TV shows making fun of the nineties and all of that.

All my friends wore trench coats to school and then Columbine happened and all my friends got suspended is the era of high school that I was in.

PRINCE: I appreciate that answer 'cause I always like asking that question 'cause I do feel like for anyone that people have an idea of, I always like to just hear like, what was younger you like in your own Oh yeah.

Could you talk about your radicalization process, however you see it. I'm sure there's a lot of different layers and different [00:03:00] moments. Could you kind of talk about the beginnings of that? Like, I feel like talking about high school a little bit kind of nods to that, but how would you kind of describe your radicalization process?

MARGARET: In high school I was kind of like a rebel without a cause type of a kid. And the first cause that I found was we like started the Gay Straight Alliance at my high school. And it's funny 'cause all of us were theoretically straight people starting, in the end, like I think one of us was straight. The way our GSA started was kind of cute.

I had been going to these regional GSA meetings as an ally or whatever. I was like, for some reason I just like hanging out with lesbians. That's like my thing. I had been going as an ally and then all of a sudden these two teachers who were obviously gay, but they weren't out. It was the woman gym teacher and the social studies teacher with a hyphenated last name.

They like cornered me in the Stairwell where all me, and like the trench coat kids hung out and they were like, did you know that teachers aren't allowed to start student groups? I was like, huh. And they were like, here's all the paperwork for a gay straight alliance at this school. And this was in an era where the next school over.

The president of the GSA got hospitalized, like in a homophobic attack. And so we had this [00:04:00] very, like we're all a bunch of like punks and weirdos and one of the main people is this hardcore kid. So we all had this like kind of posturing where we'd walk around and talk about respecting gay rights and stuff like that.

But other than that, I didn't have a ton of politics in high school. I was a little bit confused. I took an online quiz in the nineties that told me I was a libertarian because it was made by the libertarian party, For about like two months, I was like, I guess I'm a libertarian. And then my communist girlfriend was like, no, corporations will just run everything.

And I was like, I don't have a counterpoint, but I don't wanna be a communist, as I understood it at the time, you know, authoritarian communism and all that. Right? So I became like a lackluster social democrat. I wore a little Nader pin for the 2000 election and I don't know, but I didn't really care much about it.

And then. On February 2nd, 2002, I became an anarchist. I have a birthday. It was the era of anti-globalization protests. There was one coming up in New York City where I was, I was going to art school and you know, my like punk friend was like, Hey, you would enjoy going to this. And I was like, ah, I don't know all that activist stuff.

I don't know about it. And then I did a [00:05:00] bunch of research into it and the anarchists. Seemed really interesting. And if nothing else, they were, they were wearing masks, which was illegal in New York City and they were like, well, we don't care. We're doing it anyway. And that kind of thing really appealed to me.

Right. And so I showed up and I already wear all black anyway 'cause I'm a weird goth kid. I find someone wearing all black and a mask and I walk up and I'm like, Hey, what's anarchism about? And he just was like, well, we hate capitalism and the state. I was like, well, what do you do about it? He was like, well, we build up alternative institutions while destroying the ones that are destroying the world.

And I was like, do you have an extra mask? And he was like, I do. And he gave me a mask. Breaking in socially was way harder, but breaking in politically was easy.

JORDAN: I always love hearing that story because February 2nd is Groundhog's Day. Uh, so it's a very powerful date for me. So it adds another thing to celebrate.

When does Steampunk Magazine come into the picture? oh Lord. Writing these zines. 'cause I mean, I was looking up stuff, writing zines since you were like a little ute. Yeah. And now using [00:06:00] it as more propaganda and then how does, finding that politics with anarchism help carve your imagination into steampunk?

You were already kind of like geeky, then saw the potentials of speculative fiction and escape home. What were the vibes for you?

MARGARET: I was a kid who escaped into books my whole childhood. Even though I was cool and did drugs and rode my bike around and stole stuff. I mostly read books.

I got through a lot of bullying and stuff by escaping into books. This is some chicken and egg problem here with the bullying and the reading, my dad was actually a zine Stir. My dad, who's also a science fiction writer, published a magazine. It was just a staple together. It was a zine, and he published a zine of like his kids' writings and his writings and a bunch of other weird stuff and art, and mailed it out to a mailing list of about

200 or so people in the eighties. So my earliest published writings are terrible stories I wrote when I was like five that are in my dad's magazine. And then by high school I was making terrible poetry zines and I also tried to start a punk fan zine and got a bunch of demo tapes mailed to me and stuff, and put out like [00:07:00] two episodes with my best friend who came out as trans years before I did.

After that neither of us were anarchists yet. We both ended up trans women anarchists. A lot of my generation where I grew up. All of us now have politics, but none of us did at the time. I feel like I grew up in a place in a time where politics was not talked about and not really on people's horizon.

And so pretty soon after becoming an anarchist and traveling, I got really back into zine making. I really liked it 'cause I basically, I dropped outta college to go travel full time. The first zine I wrote is actually the name of the publishing collective I still work with. It was called Strangers in Tangled Wilderness.

I wrote a personal zine in 2003 called Strangers in Tangled Wilderness, and it's just poetry and stories about traveling and things. The next year I put out a zine feminist theory for anarchist men and I started doing comics. Somewhere around that time I did a comic called the Super Happy and Arco Fun Pages, and so I just like made zines and traveled.

And then around that time for Steampunk in particular, there was this group in New York City of like. [00:08:00] Older, cool, weird anarchists who published a, a newspaper called the New York Rat, and I went to the New York Rat's website. It was at the era where you wouldn't have just a.com, you know, like a.com/ New York Rat.

And I went to the top level domain and I looked at it and they also had this steampunk manifesto, and I'd never heard of Steam Punk, and it was not what Steam Punk became. This manifesto, it was about the colonized stealing explosives from the colonizers to blow everyone up. How big, brutal, honest machines that like are dangerous to everyone, including the people using it.

Just like relationship to technology that I found really interesting, kind of like a, a mad science anarchism vibe with like a Victorian flare. In the same way that cyberpunk critiques sort of the modern dystopia steampunk theoretically was an attempt to critique the start of capitalism and the start of industrialization and the peak of.

Colonization and it looked at having that intervention earlier and doing it through speculative fiction and all of those things really appealed to me. I started a zine called Steampunk Magazine in probably. I didn't know that Steampunk [00:09:00] was just about to become a thing, so I was in on the ground floor of this massive pop culture explosion, and it was very interesting.

It was the first time that any of my work had wide reach, but also it was really hard to navigate because I would go to these spaces and I would meet. Steampunk Emma Goldman at these spaces. I would meet all of these amazing radical people and all, there's like a huge crew of, people of color who were specifically using it as an intervention in the capitalism and, and there's like all this interesting stuff happening, but it was wrapped up into this veneer that, just kind of became more and more devoid of politics and more and more devoid of meaning and became just about the surface level aesthetics

To the point where it kind of became a thing I sort of wanted to distance myself from which I'm not even proud of because that's also just kind of reactive. Like on some level I'm like, well, I still like all of this, like the aesthetics and all the stuff that I was.

Into and all the messages that, were involved in it.

JORDAN: You were talking about how like people had politics but didn't talk about it. I think about how like now in certain like activisty cliquey spaces, it's very, we all talk politics and there's [00:10:00] even that one thing where the FBI was like, we can't infiltrate anarchist circles because they read too many fucking books.

And then. I was kind of thinking, do we talk too much politics now? Were we not talking enough in certain spaces, but things were still happening? So then there's that like overall anarchist ethos of do we need to name the politic to walk the politic? And then there's the point of education or like, do we actually need to constantly name the politic every once in a while to walk it and like be able to cycle through and learn from things.

I dunno. I think about that when you talk about like watching the scene and around aesthetics and a subculture blow up into pop culture. Having just the aesthetic. Yeah. Like be what's around. But I guess that makes sense of what's gonna stay in the pop culture.

MARGARET: This happens to every subculture. Maybe not, but almost every subculture I've ever looked at starts as a really radical intervention into society.

And I think that punk and hip hop are two of the clearest and strongest examples of coming in with this. There's a bunch of bad shit more against it, and [00:11:00] we're gonna do stuff, DIY, and we're gonna live beautiful, crazy, weird, interesting lives. And then as it becomes monetized, it becomes more complicated.

I'm not even like, and then everyone sold out like, I don't care. Like people should try and get money from their work. Like that makes sense to me. It absolutely becomes more and more about the surface level aspects of it. I actually think hip hop and punk are two of the best examples of ways of fighting that because their radical politics are so.

Baked in that it's harder to strip them away successfully. There has been successful stripping away and there's a lot of, popular groups and things that have absolutely terrible politics or, you know, no politics at all or whatever, right? But like, you dig down into the core of it and you're still finding messages.

And I think that keeping certain things named has been a really useful way of fighting that. it's really complicated. I actually kinda wanna hear what you all have to say about anarchism as identity and things like that too. Because for me, when I discovered anarchism, it was like a lens had been put in front of my blurry vision, and so suddenly I [00:12:00] could see the things that I knew the outlines of.

Like, I remember walking around being like, what if chain stores are bad? They take money away from neighborhoods. I hadn't been able to be like, the problem is capitalism, and so naming it gave me access to all this stuff. But it's also inherently limiting. And of course, obviously anarchism has a, a particular reputation in everyone's minds.

It's a different reputation for everyone. People are like, well, I don't wanna be an anarchist because of X, Y, and Z. It's the same way that like, I didn't wanna be a communist until probably like two years ago. I finally was like, whatever, I'm an anarchist communist, it's fine. You know,

JORDAN: that's real,

MARGARET: but you're like, well, at the core of it the theoretical definition of communism like matches up with what I want.

I just disagree with the capital C version. That has taken up a lot of space in the conversation to the point where I don't consider it a useful word to try and reclaim. Other people feel that way about anarchism and are like, well, the politics and the messaging is more important. You know, we can call it whatever we want and it's fine.

I get that. For me, giving it its name accesses this beautiful, proud history that I'm [00:13:00] incredibly honored to be part of. Although, I will say I think that the most useful intervention into anarchism as a concept in the past, like decade or so, has been the sort of broadening of it into the anarchic sphere.

I mostly have seen come out of like, indigenous anarchic crowds that have basically said like, we agree with these concepts and goals, but we're not coming out of like a Western Enlightenment tradition. And so anarchism. Might be the Western Enlightenment version, but it is part, it's not bad, but it is part of a larger anarchic umbrella.

That's been something I've been really excited about because the more I read anarchist history, the more I'm like, well, most of our best parts came from people who are indigenous and or we're like part of indigenous cultures in various ways.

JORDAN: What got me into anarchism was indigenous anarchists.

Citing and recommending black anarchists is what got me into like anarchism in general, like I think William C. Anderson, it might have been a Lorenzo Irving quote. It's like I don't run away from it, but I don't run towards it. [00:14:00]

MARGARET: Yeah, that makes sense.

JORDAN: But I also like, I kind of do run towards it and like, I actually do.

PRINCE: Yeah, I mean it's a really good question, especially your point about like the trench coats and then Columbine happening and I guess it just makes me think about aesthetic behavior and how I look at how the internet and social media at least. 'cause I feel like I got my first desktop when I was like eight.

And then I got my first laptop when I was 12 and I started writing. Mm-hmm. And I remember looking at other people in school and seeing what they wore. And there were a few people that wore like really long sleeves and striped long sleeves and had piercings and other things. And I saw a certain kind of aesthetic behavior.

But because of growing up in an immigrant family, being told that I should be straight edge, all these other things, I feel like there were glimmers of my politics. That I could see in the world that I kind of resonated with. And then in college is when I met other people that I look back now and I'm like, oh, those were the anarchists.

Like those were the people when we were doing student demonstrations. They'd be like, why not Occupy? Or maybe we should demand that the university [00:15:00] change their whole model around funding or tuition or anything. And then. I remember when I moved to Seattle after college, I met this student organizer who was a grad student at uw, and basically I connected with her on Facebook and I was like, Hey, I'm trying to meet down people here.

And she was like, oh, come to this book club. And I went to the book club and ended up just being people that went out at night tagging. And there wasn't a moment in my mind where I was like, oh, maybe I shouldn't be here or whatever. I feel like it was other black people. Mm-hmm. I could tell that they were really down in a way that resonated with what I was into in college.

Kind of like, do you run towards it or away from it? And I feel like there are so many moments in my life where when I had the moment, the chance to run towards it, I usually did because some part of me had always been waiting. I agree with you in like the books and everything. 'cause even growing up it was kind of like, I usually like books about young people that broke the rules on some level, even if it was coming of age as kind of like a general genre where I'm like, it's about breaking the rules theoretically.

So I guess I think about it in that way. [00:16:00]

JORDAN: Is it time for like the local community space, local info shop time, how explicitly anarchist, uh, other things like that, but also being like, there are things that brought me to anarchism when I think about like the forest defense campaigns that I explicitly like looked towards and were like.

Oh, those are cool. Those are things that would be interesting. I'd be interested in supporting, especially finding anarchism through like environmentalism and those kind of advocacy scenes and slowly looking around and being like, oh yeah, like I did find anarchism and then was like, I'm gonna go towards them and find who's there only to be at.

Places and be like, oh, we're not talking about anarchism. Mm-hmm. We are in meetings, we are figuring things out, and then maybe at the end of the night when everyone's chilling, we're having discussions about anarchism and stuff like that, but it's not like. Oh, hello. Welcome person. Hello Twig. I like to show you Krakin 1 0 1.

Have you heard of Yeah, totally. Visual Aid, the graphic novel that just came out, [00:17:00] like you should sit down and read it in the corner before you can come to the meetings. I don't know, I feel like it does work as identity as a thing to drive a social space, but at the same time I do like, especially as like a history nerd, I see the limitations, but then I also see the points where it had millions of people behind it and hundreds of thousands and was the predominant social thing.

Totally. So I'm like. Maybe we should be what me and my friends were saying the other day, full frontal anarchists and then just run into the world and 'cause especially with the internet, this amount of decentralized access to information. I was just listening to the Cool Zone Media, world War 3.5 thing and I was like, maybe World 3.5 is that's what the proliferation of it like.

I love seeing how the technology can be used and is readapted.

MARGARET: I like running towards anarchism. I like black flags and black and red flags, and black and green flags and black and purple flags, and they make me feel connected to something. And one of my friends who's this longtime anarchist environmental organizer was giving a, I think a medic training at a big [00:18:00] environmental camp doesn't go there and be.

Hey, I'm the longtime organizer and I'm an anarchist, and so here, therefore the following, when you're given a medic training, you don't have to be like, as an anarchist, I think you should use a tourniquet on the following type of wounds, but she was realizing at some point a lot of the people who were there were sort of vaguely shit talking anarchism or vaguely like feeling really distant from anarchism and, and not really understanding it without realizing about half the people putting in the work to make the thing happen.

Were anarchists. I actually think that there's an advantage to being open about being an anarchist and having some anarchist pride without having any anarchist. Like chauvinism without having any like, and therefore you need to be. 'cause we don't want people who get into positions, get into ideologies 'cause they're bullied into it, or even peer pressured into it.

We have a harder task than most ideological positions and that we're trying to develop free thinking individuals. And so we can't necessarily be like, here's all the answers. And that's one of the beautiful things about anarchism. Like most of my books are not Anarchy. [00:19:00] Some of them are right.

A country of ghost is Anarchy. But they're also not. Really like subtle, hidden things. And I try to be very upfront about it, so if people do a little bit more work and look into what I am, and I've had a lot of success with that. I thought it was gonna like lock me out of mainstream publishing.

It didn't. I went to a science fiction convention and one of my older friends who's been a science fiction writer for decades was showing me around, was like, you have to meet Margaret, she's an anarchist. And then it's like. Guy whose science fiction books I read was a kid, I'm not gonna name him, about how he behaves towards women.

So I don't want to claim him. He turns and he's like. Me too. I was really excited about that. 'cause I'd read his book as a kid and then later one of my friends was like, oh, that man grabbed my butt. So that's not necessarily the best example, but we are everywhere. When I read history, I see certain things written outta history over and over and over again.

And it's funny 'cause even anarchist historians, for some reason a lot of the anarchist historians writing in the middle of the 20th century just didn't know women existed. And then also there was a certain race blindness. Anarchists were doing for a [00:20:00] lot of the 20th century. That means that non-white anarchists who fought in the Spanish revolution weren't like marked as other, which is, has some advantages, right?

But it also means that people just think that all the people fighting in the republic were white people. And they're like, that sucks. Most of them were. And there's complicated things about race in the Spanish Civil War. Actually. Marking identity, I think has a real advantage as long as we can stay away from bigotry and chauvinism around.

PRINCE: And I'll add to that because I've been thinking about this a lot lately, especially. Post-election, whatever the fuck. But basically I had a long conversation with my best friend who's black, and in a lot of ways I can view her as like relatively anti-authoritarian and know she's into stealing and all these other things, but mm-hmm.

We had this conversation where basically she was just. Being extremely xenophobic and was like, I don't think it's gonna be that bad for immigration if Trump wins and using a lot of those same talking points. And in that way, and like even doing this podcast, I feel like it's been useful for us to kind of come back to these terms again and again.

And I feel like even when we talk, it's like there's [00:21:00] distinctions in how we view things or describe them. I do think being recognizable on some level is important because even if I think of my best friend, I'm like, I don't know if there's anyone else in your life that could articulate some of the politics of anarchism in the way that I can.

But I also know we both are into stealing. We're both anti-authoritarian on some level. So it's like, how do you bridge those gaps? 'cause even when I look at black culture, I'm like, there's so much that is anti-authoritarian on a class level. If you look at like mm-hmm. I dunno, black folks, marginalized folks.

And then once you go up through the ranks, that kind of goes away. But what would it mean for there to be like shared space or for there to be like a more legible space, which I think is one of the projects that we're kind of hoping for out of this. 'cause I do feel like. If someone's anti-authoritarian, they can either go towards like super fucking weird, alt-right shit, or it's like, yeah, super far left, and it's like, which way do you go?

How do you get there? Interesting. Based on like your identity, your class, how recognizable you are, how do you feel like your relationship to anarchism has changed [00:22:00] through time?

MARGARET: There's this whole thing that when you get older, you're supposed to become more conservative or whatever. And at first I was like, wow, that's clearly not happening, right?

Because my anarchism keeps deepening, but I found what happens instead for me, it becomes a little bit more pliable and more nuanced, and it has become less of like a zealotry and more like the core aspect of my personality. I think about how to tie it back into aesthetics. When I was a teenager and I was like dressing goth or whatever, it was sort of a costume, right?

But not in a bad way. Because I was 16, I didn't know I was just trying things out and now my aesthetic tastes are just in me, and so when I wear things, they don't tend to look like costumes. Well, that's not true. I wear cloak sometimes, and there's no way you can wear a cloak without it looking like a costume.

But overall, right. I believe in a world where we can get some clo back. Yeah, no, cloaks are normal in 2025. I don't know what you're talking about. we are in a brief blip of non cloak all of human society until like 1910 or 20 or something. Cloak then no cloak. When cloak again, it's really comfy.

It's like a blanket. Anarchism was a thing I was trying [00:23:00] on, and so I had to really not force it, but I was forceful with it. Now it isn't, and I have easier times talking with non anarchists. I have easier times seeing and understanding non anarchist positions. On the other hand, I also almost have the opposite effect where like.

I just like can't, with authoritarian socialism, I keep trying to come around, not to be in favor of Stalin or Lenin or something, but to be more understanding and appreciative of, because people who have subscribed to Marxism have done amazing things throughout history, but these larger structures keep doing evil stuff and that keeps reminding me why I'm an anarchist in the same way that a lot of individual Christians do so much, basically mutual aid, right.

Then like, if you go and do border work, and I haven't done border work, but I'm using an example that my friend talks about all the time, right? So you go down to the border and it's all just like anarchists and Christians, but then the larger structures are where you start getting into all the stuff that can create Christian nationalism and, you know, do all of this horrible stuff.

Whereas the, like, I don't know, I follow a guy who says, you're supposed to be nice to [00:24:00] people. I'm like, that rules, and so with Marxism, I feel that way where I'm like, okay, you all are just like. I have a whole weird, the church's hankies theory, but that's a separate conversation. No, I mean, that's

JORDAN: Like what's the rank and file doing? Because even, like who's the rank and file in the USSR, who was in the Soviets, doing things? Who was in the guard? Who was in these. Christian groups that are done at the border who are in the anarchist groups. The structure is telling you we're going down here

PRINCE: like with the Christian groups.

I dunno. Yeah, I like that you mentioned that point. 'cause I was doing some border stuff not too long ago and I feel like I understand some of the stuff that you're saying. I was even thinking about this with at least like religion recently or like hyper Christianity where a part of my problem with it, even on just like an emotional level, is people that are so.

Christian or religious, that religion comes before, like seeing the person right in front of them or the people in front of them and how, I think in a lot of ways, anarchism demands that we turn away from that. Or like people that are religious that don't do that [00:25:00] and then like they acknowledge humanity first.

Like those are the religious people I fuck with. 'cause I'm like, oh, you're. There's an internal sense of autonomy that's guiding you, even with this belief system, which I think is necessary if you want whatever aid or help you're offering to be the most humanizing it can be because I mean you can help, like what is help if it's based on the more innocent victim versus the lesser innocent victim in terms of like if we're thinking about aid work.

MARGARET: No, and I think actually that idea that you're saying that makes a lot of sense to me. This idea of when you interact with someone, do you first and foremost think Christianity tells me to do the following, or do you do a thing and then it ties into your Christian beliefs? When I was a teenager as a goth, I went out and bought clothes that I thought were goth.

Now I just buy the clothes that I like. The best description for how I dress ismy partner calls me tactical dog mom. When I was younger, a younger anarchist. I would kind of run things through an anarchist filter because it's a lens that had been so useful to me.

So I was [00:26:00] like, what does anarchism say about the following? And now I just say like, well, what do I say about the following? And it keeps lining up with anarchism. It helps that I read a lot of anarchists and I seek out anarchist ideas and I expose myself to more of them. But if I run into something where I disagree.

I don't feel, and this is an advantage of anarchism as I think it acknowledges this, right? And it's why I think anarchism, even if anarchic is the larger umbrella, even sort of anarchism is also a huge umbrella. We can disagree with each other and still be roughly on the same side and it comes across.

'cause there are people who do anarchist mutual aid where they're like. Actually, I dunno if these people actually exist or if they exist in my own head. I'm not actually sure. But you could imagine someone being like, here's a sandwich, thank ock. You know? Right. they wouldn't literally quite say that, but like, you know, they'd be like, welcome to anarchy, food anarchy.

And it's like, and at that point it's just a recruitment tactic and like the right wing does that and everyone does that. And so if someone is giving away food or helping at the border because. They see all humanity as equal and believe [00:27:00] that is what Christ taught. That's chill. But if people do it because like, well, I guess since I'm a Christian, I have to do this thing, or here's a cookie, thank God, then that's when it gets less nice.

JORDAN: That's the thing that can be baked into a lot of structures. I feel like that's what's very interesting about talking to religious people. What is afterlife to you and how does that affect your moral and then material? Worldview.

PRINCE: I don't know if this makes any sense, but I think about how in the left we describe it as radicalization, but for Christians they might describe it as enlightenment or something.

And, and I guess I wonder about the distinctions between those processes because in one sense, if I'm thinking of Christianity or like religion, like the process of being enlightened or baptized or saved, it's a cleansing process. It makes you more innocent as opposed to like far leftism or anarchism where.

When I was witnessing work happening at the border, it was more the willingness to be anti-authoritarian, the willingness to be unclean, the willingness to do [00:28:00] work that could potentially be criminalized, and how the function of that enlightenment process is interesting to me because the deeper I go into anarchism, the further it's allowed me to feel human, even in like queerness, my blackness, all of the ways that I, I want to be a good person, but also the ways that I'm willing to be bad to have there be a better world.

JORDAN: It's like when and what will you decide to have or be acceptable with a nuanced moral stance? And everybody does that. That's what authoritarian socialists will be like. This is just what has to be done. Totally. Um, and this will be the means and ends or whatever. Which is why when we were doing this like direct action series, one of the definitions we used it was ban's.

The most beautiful part about direct action is that a means and an ends.

MARGARET: Yeah,

JORDAN: not finding that they're both gonna be the exact same when, whatever revolution or whatever happens after the action, after us directly taking an [00:29:00] unmediated action to get our resources or, and then manage such resources, which is actually something.

That brings me back to a question I've had a long time. The piece that sparked part of my interest in anarchism, especially as someone who has like a tiny interest in economics history. What can be done? What's the future? That's what I love about speculative fiction because I'm like, okay, we have to watch people go through the world.

What does that actually look like? And I loved, take what you need and compost the rest. I'm just curious about the lifetime of that essay. Because there's multiple versions online that have different, longer and shorter versions of it, and that seems like a pretty early tangled in the wilderness.

I was wondering if that was just solo or when there was a team.

MARGARET: That piece. There's a couple different pieces that are variously called like post siv and take what you need and compost the rest I think that was the name of the collection of essays that I put together. A while ago. It was probably like 2007 or oh eight.

I was [00:30:00] living in the Pacific Northwest and. waters I was swimming in was Primi Vista anarchism and green anarchism, and we were all a bunch of earth first kids who did a lot of tree sitting and things like that. But we started having more and more critiques of what we saw as the Primi Vista position.

I don't think we like straw man primitivism, but none of us were like big theory readers, so we weren't responding to zin. We were responding to the waters we were swimming in, which was a certain type of green anarchism. Our basic position was, look, we agree with you about like chaos and organic structuring, and the idea that this.

Direction towards what could be called civilization has probably destroyed the world. And like, uh, yeah, 20 years later, we're pretty sure we're right about that, but we disagree with some of what we see presented as the core tenets of prim in terms of the idea of A response that is returning to a quote unquote, pretty civilized way of being.

And we were like, you know, we like Lens Grinders. We like the concepts of looking at technology, like the concept of looking at how to solve problems and [00:31:00] systematizing it enough to solve problems on enough of a scale. And you know, we like certain things. God, now that I have read more theory, it's basically like a dialectical approach to tism versus civilization in that it was like,

JORDAN: oh, my friend is gonna love to hear you say that.

MARGARET: Oh no, God, I hate how much I, because I always hated big theory war. 'cause it's like I don't, I went to art school, dropped out. I only like ride trains and fight the government. I'm really bad at riding trains. I'm also pretty bad at fighting the government. I'll be real. I redeveloped in my head what I called triangle thinking, which was like, well, you have two sides and they seem to be opposites.

But then there's a beautiful third thing that can be developed by contrasting these things, there's like 18 versions of dialectics, but that's one of them. And I just called it triangle thinking. Subconsciously that's what we were doing. There's about four or five of us in the room, and we came up with the basic ideas of post siv as a theory.

And it's interesting because that essay has had, in some ways, more legs than anything I've written, but. I wouldn't write the same thing again. The reason I wouldn't is I think it's based on a false dichotomy of civilization versus anti [00:32:00] civilization. I think that that is enlightenment thinking. That has infiltrated anarchist theory to present this idea of the sort of.

Primitive versus the civilized. You know, there was like anthropological ways of understanding the development of civilizations. It's like this hierarchy towards more and more civilization. And we were like against that, and I'm still against that, but now I'm also against it as a concept. I've been kind of moving towards that for a while.

But then I read the book, the Dawn of Everything by the two Davids. It basically presents this idea that everything that we think anthropologically based on enlightenment thinking is wrong. And what's interesting is that that concept gets a lot of pushback because it undermines. Most Western political ideology because it basically says Marx was wrong.

It also says zin, et cetera are wrong. What it doesn't say is that like indigenous and arcs are wrong. Well, I mean, I'm sure there's individuals who feel very differently about it. It basically says there is not a linear concept of civilization. And so honestly, when people ask me How do I feel about post now?

My answer sort of like redone of everything, I don't [00:33:00] know.

JORDAN: Yeah, I definitely came to it in that kind of way. Read it and then tried to read Zer in, and then was like why, why, when there's post now. Um, then like one of my favorite printing mishaps was when I accidentally printed the whole zine and sticker paper so that we just zed it around the whole city.

Um, and it's amazing version of flowers and stuff on it. So it was really beautiful. I was like, okay, this works out. This was only like a $30 fuck up. But it's fine.

MARGARET: Oh, the story about how the rest of the essays came about was that my first writing job, my first paid writing job was that Alan Moore asked me to write more post civ and publish it in his magazine.

JORDAN: Wow. I love that connection to you and Alan Moore because we're gonna have like a black watchman analysis and series of, oh shit. I'll be curious. You just did a tour. You also have toured. Done events as a musician, you talk about wanting to like make atmosphere, [00:34:00] make an event. Well, you've also had all these roots all over the country as a traveler, and now gets to use this to revisit some friends.

What is I guess if you had to not have a take, but re-seeing again. The anarchist scene, the literary scene, doing the whole outta your car on the traveling around thing again, how was that for you and what are the reflections?

MARGARET: It was interesting on a lot of levels. It was very tiring in a way that I was really feeling my age.

I'm in my early forties and you know, I spent most of my. Twenties to my mid thirties living out of vehicles or backpacks or whatever and just traveling. I'm like, oh, I don't wanna do that all the time anymore. Part of it's that I have a very reactive dog who I love very dearly, who doesn't travel incredibly well.

So that was like an added stress the whole time. I mean, I'm kind of hoping I'll do it about once a year. And because I would say before 2020 when I kind of fell into hermit world, I felt like I usually had the pulse of the anarchist movement in the United States. And I used to travel [00:35:00] some in Europe and stuff too, right?

And so I had a little bit of that pulse too, and I felt that that kept me feeling part of things. And then for the past, like four years or so, I felt kind of a part. A lot of it's just like literally I have chosen a certain level of isolation to focus on my work. And also at the beginning of COVID, I was just very COVID conscious.

A lot of people sort of fell out of society a little bit at that point. It was nice. Yeah, as you kind of pointed out to go back and see how things are going. And it was kind of useful because there was this thing that was happening as I was sort of aging and I was doing less direct action. Is that I felt like this tension where I, I still felt like I was one of the people on the ground, but I kind of wasn't.

I didn't know how to fit in. And now with a little bit more space, I'm like, oh, now I'm a cheerleader for you, for everyone. Like now I'm like, we can do it everyone. I don't really feel a need to like stick my head in strategically or tactically on anything. That's the kind of decisions that needs to be made by the people making the decisions that are risky.

It's been kind of nice to just sort of be like, I [00:36:00] write books, I read history. I tell people history. I try not to tell people what to do. I see myself as a support role, and it took a long time for me to accept being a support role person because. But I mean, you know, part of the reason a support role person is that I gave myself enough trauma in my twenties, and then I spent my thirties dealing with that trauma and now in my forties, I'm hoping I can just kind of get some shit done.

Or honestly, with the way the world's working, I'm, it might just be back in the fray. Who knows?

JORDAN: So it's a bounce back from burnout story. Yeah, and I hope so. I'm in the middle of it, but so far it's the vision, it's doable. It's lovely to see people. Actually succeed to process through things and still walk and talk while we're all processing through things.

I think that's something me, like I got into a lot of youth activism at the beginning and it was really dope, but it was like, do we have people that survive? Yeah. Can we? Mm-hmm. And like, especially with a politic, it can get doomed. Quick and heavy. So it's like, oh wait, it is about [00:37:00] us and us as surviving.

And the overall thing is we want be able to live our lives. Yeah. So it's like, have the space to do that and like they say, tear down the systems that are destroying us well by creating alternatives to ones that we can live.

PRINCE: I feel like what you just said is very interesting. 'cause I, I kind of relate in a loose sense.

Like my, I published a book in 2022 and it's like about a lot of different things, but a lot of it is about anarchy, immigration, gender, all these things. But I guess I wonder like with the past number of years and how, you said this recent tour kind of brought you back into certain folds or spaces that you felt maybe a bit distanced from.

Do you feel like when you go on tour and you're. In front of these audiences and talking to people about your work and answering all these questions about your work, do you feel like there are common misconceptions that people pick up on in your work? Even if it's how they read it politically or like where the questions are kind of oriented towards you?

'cause I was always kind of interested in that when I was on book tour going to random cities. Maybe you know, people, maybe you don't, and [00:38:00] you kind of find these patterns. Like were there certain patterns in the conversations or questions you were being asked that you found?

MARGARET: So overall, now that I write fiction, mostly I'm a little bit insulated from that.

My first book tour, ironically, it was about fiction, but it was a non-fiction book about fiction. It was a bunch of interviews with fiction writers who were anarchists, and I found myself like challenged more, that's not necessarily bad, although I think that there is a kind of weird, sometimes it is bad.

I think the way that we argue our politics, but anyone who presents a theory, people should be able to critique that theory. Like I remember my first book tour, I was staying with some, one of my friend's friends at this house in DC and they're all having this conversation. I think they're actually talking about like civilization versus anti civilization.

And I was like, well, I think. Then they turn to me and go, we already know what you think. And then they go back to talking to each other. Oh my God. And like I was like, is this just my future now? You know, everyone thinks they know me because they know my work or whatever. Right. I found a little bit less of that [00:39:00] once I started working in this sphere that more actively talks about.

Questions and answers by doing fiction. There are things that people assume about me, and some of them are just sort of the usual parasocial thing. Like parasocial is an interesting word because I have parasocial relationships with people too. Like I'm a podcaster and you all are podcasters and you all are probably already getting this.

And it's like podcasting is a parasocial machine. Yeah. You know?

JORDAN: Yeah. How do you fight that? And it's like, and what do you fight from it? Because they're still like, oh, maybe you want to build community. It's like the whole thing of like, we're being like, oh, do we wanna actually Build a discord.

MARGARET: Maybe podcasts like yours do help a lot of like creating community, always a purpose to having media within our ranks, and especially media that is representative of different experiences and cultures. You know, because then it's like. Okay, we all share this ideology, like there was a problem in the early aughts where anarchism meant punk.

I was sort of allowed in by my proximity to punk because as a goth I looked like a punk and I had big nose ring and shit. That's not a reason to let someone into an anarchist space. It's not a reason to keep someone out either. [00:40:00] Anarchist punk stuff. Kept the flame alive and deserves a lot of credit. But like that can't be it.

We can't have a subculture as the fucking goal. Subculture is useful and creating community and culture is useful, especially if it's different ones. But the parasocial thing, what I choose to do is I don't lie. But I also control what I talk about. I don't really talk about my family. I love my family. I don't wanna drag 'em into this.

I don't really talk about my relationships, same thing. Those aren't part of what I'm presenting to the world. Parasocial relationships aren't inherently bad. If we acknowledge and understand them as what they are. I listen to podcasts and so I have parasocial relationships with all the people I listen to podcasts of.

I listen to them every day. Within anarchism, we are genuinely all equal, and we try not to hold people up on pedestals, and so people can talk to me, right? On the other hand, I'm socially full. It's not that I'm like, oh, I'm better than other people. It's more that I'm like, I hate my phone. It makes noises that interrupt me while I'm trying to read books and play with my dog

I don't remember what the question was. I'm sorry. [00:41:00]

PRINCE: Book tour. What the experience was in terms of how people intake, the different kinds of writing that you do. What kind of patterns or questions tend to come up?

MARGARET: Honestly, I've just found a really positive response, not, not necessarily responsive, like you're the best or whatever.

I had this hypothesis with that first book that creating culture had a purpose. Um, because fiction was not a big part of the anarchist scene that I was part of to any appreciable degree, and it was seen as like, it's almost like Emma Goldman and if I can't dance, it's not my revolution thing.

Dance parties were part of our culture, but other cultural stuff like art. And besides political posters in graffiti, actually at the start, anarchists were shit graffiti artists. We fixed that one. I'm really glad. But so am I somewhere There's little stick figures I drew on walls like 20 years ago. Probably not.

They've probably all been buffed out. I had this hypothesis that there's a point to writing fiction and I didn't come up with this hypothesis. I mean, I literally it's a book of me learning this hypothesis from other people. Then going on this tour was just like, oh, the answer's yes. There was a point to it [00:42:00] in specific, weird, tangible ways where someone told me that her trans brother was no longer homeless because her right wing parents read some of my books and understood trans people better and let him back in.

And I'm like, well dad, that's it. I'm done. I have but I'm actually curious about your book tour and like what were the conceptions that people had about you and your work that like, did or didn't make sense? I mean,

PRINCE: it was interesting what things people attached to rather than others. Like a lot of people attached to my relationship with my mother.

A lot of people attached to the chapter I wrote about Standing Rock, a lot of people attached to BLM and college organizing stuff. But then I was like, no one wants to talk about the threesome or stealing or any of these other like really fun things that are in the book. I think it was interesting what they fixated on because it jumps through time and there's a lot of different things.

And then I also think just age wise, like I think a lot of people were like, oh, you're so young to write a memoir. And so I feel like that colored a lot of it too. And so it felt mm-hmm. Strange in some ways, talking to [00:43:00] people that were older than me about my life and then having people come up to sign the book or talk to me after, and that was.

Interesting. And I also feel like most people wanted to engage with the book emotionally and maybe not as much politically unless they were maybe like queer. For my New York book event, I spoke to Jamal Joseph, who is part of the Panther 21, and he was definitely really asking a lot of questions about fascism and repression and kind of the emotional life and the political life and where they mer with my book, at least the last chapter.

Is auto fiction. And I feel like I didn't get any questions about that at all, and I was just like, oh my God, I can't believe your mom lied to you about your dad being dead. And I'm like, he is dead. So I don't, there were just so many things where I was like, this is just an interesting experiment in a way.

MARGARET: There's a level of condescending that people are to younger writers that like, I am willing to bet also being black makes worse. The people who aren't the people you expect to be a writer. I remember once, actually, I went to the Steampunk convention, [00:44:00] uh, maybe it was Dragon Con. It was a big nerd convention, and I went as an author and I went to go get my badge and they were like, so which band are you with?

And I'm like. No, I'm here as an author and they like wouldn't understand, you know, that I was like, I write books the way I like dress. People are like, ah, yes, the band. And then I almost feel bad 'cause I'm like, well I am in a band, but that's not why I am here. I swear I'm an author. Oh God, there's this story that I want to know better and I'm actually, I need to do an episode about him.

On this first tour I went on, I talked about a bunch of anarchist fiction writers and one of 'em was a guy, uh, named Bud Zo. Marcher Marra, and he was from Zimbabwe. I think he was from Rhodesia like at the time, and he like made his way to fucking halls of Power England as a writer. Was like, I guess like sort of the black Henry Miller to people or something.

Right. It has been a long time since I've thought about this story and people just treated him like shit just fucking constantly. he like won a literary award, but no one would fucking treat him with [00:45:00] any respect. So he just started throwing the dishes at the ceiling during the banquet and shit, and like stormed out.

Moved back to no longer Rhodesia and then died of AIDS homeless on the streets. Honestly, he was fucking interesting. And just like the idea that people just don't take people who they don't expect to be writers. Seriously. It's so annoying. 'cause at the same time you also run across this thing where people think that the only reason you were able to write a book was because you had the time to do it.

PRINCE: Anyone could write a book. Yeah. And I'm just like, maybe I chose. To not take, I don't know, it's just like the time I'm like, I'm poor. Yeah. Like, but I'm poor, but I don't have a high, I don't know. Yeah. Even that is interesting, the confusion around that. Like I remember even doing a workshop on my memoir before I like sold it or whatever, and I

Had basically gotten a few drafts in and I remember an older writer in this workshop was like, I think you're too young to write this. Just turn it into a novel. And then a year later I had a book deal. So I was just like, yeah, fuck you guy. Yeah. And I just kept thinking, I grew up [00:46:00] on fan fiction and weird SMU online and that's still writing, and those are people of all ages and a lot of, I don't know, just teenagers.

and so I think there's just a strangeness to even a book also is parasocial in a sense that sometimes I remember and sometimes I forget book tour. It was a lot of weird moments where I was like, I don't think I wrote the book for this reason, but suddenly.

I'm kind of getting this moment and I feel like even those things are like strange and beautiful discoveries too.

MARGARET: Yeah. Finding what other people find in your work is really interesting and fun. And then, you know, people often quote parts of my books to me that I don't really remember, and I'm like,

JORDAN: oh, that's great.

So one question I've had as a fiction writer, do you ever write. As one of your characters or explore the world just for like dealing with personal stuff or like exploring your own self through those characters.

MARGARET: When I first started writing at a more professional level, like when I first started [00:47:00] selling short stories, almost every short story I sold was me navigating a specific trauma in my life.

Through a fictional lens. I had a moment where I was like, 'cause I was real broke at the time and so like when I sold the story for 400 bucks, it was a real fucking big deal. I was like, oh God, am I gonna run out of my own trauma to mine in order to successfully create this stuff? But it was kind of a training wheels for me.

I mean, the stories aren't training wheels level. I know I can write an emotionally expressive story if I talk about something horrible that happened to me. But eventually I got to the point where now I can write about imaginary horrible things or nice things. Some characters, I sort of map them to, you know, I have a story, I'm not gonna name which one, where it's like a sort of a love story and a post apocalypse and, and there's two characters that are in love, but it's real complicated and it's not going great.

That's just, I've listened to both sides of two of my best friends talk about their relationship for hours and hours and hours over the years and I was like, I'm writing about their relationship but in the future in a fake world.

JORDAN: Do you ever [00:48:00] like revisit those characters when it's published or done?

MARGARET: Sometimes I actually do read some of my own stories, but not always. But yeah, I do sometimes.

JORDAN: What advice, if any, in this current political moment? Would you give to us?

MARGARET: Oh, Lord. I mean, I did just go on this rant about how I shouldn't tell other people what to do, but I think I can give advice

JORDAN: As artists, as podcasters, as anarchist, peers, as whatever.

MARGARET: Okay. my advice to writers is to have three days worth of food and water and power in your house, because that's my advice to everybody. Um, and you can't write if you're dead. I would say one of the questions I got asked a bunch at various points that used to bother me, but I finally decided I'm okay with is people have asked, like from doing a history podcast for so long what has changed about my understanding of like anarchism and politics and stuff, or what advice have I [00:49:00] come up with from it?

And the main thing is that we have to actually organize, we have to actually not be afraid of building structures. We just need to be vigilant. About the shape of those structures. We need to not believe that all structures need to be permanent. You know, we need to not be more attached to the structure than the thing that the structure does.

I think about when abortion was illegal in the 1920s in Germany, millions. Of abortions a year were done by an Arco ISTs, the Jane Collective rules. And that's the story we hear about in the US when some Marxists who I think were in with the mob, but I don't necessarily in a bad, not necessarily in a bad way, I just literally, they're in crime.

So the crime people are involved, you know, ran an illegal abortion clinic that did amazing work in advance the technology of abortion and did all of this stuff right, but learning that all over the country, there was this massive network of. Abortion clinics in Germany for 10 years, basically until the rise of the Nazis.

That was run by folks who specifically, and actually, [00:50:00] interestingly, they didn't call what they did in Syla. It's part of why their history is actually really hard to dredge up. It was all the Narcos sinus also did it because basically when you need crime done, you go to the people who are good at organized crime.

And in the United States it was the mafia. And in 1920s Germany, it was a narcos sinus because what is a narco sinism, but organized crime, but in a positive way. We have shit we have to get done. I think we have a duty to attempt to accomplish it. And I think that the best means by doing that is organizing.

But I don't mean everyone should go out and join the DSA or join the blah, blah blah or whatever. Organizing can still be organic. That's okay. That's my advice. Sorry, that's a Long rant.

JORDAN: Yeah. No, that's it. No, that's beautiful. You heard it here. Organize, organize, organize. Federate.

You can't federate if you don't fucking have something to federate with. You gotta start where you're at. Then we can do big things. Yeah. It was so lovely talking to you.

MARGARET: Yeah. Thank you again. Hey, what's your book for anyone who's listening to this who hasn't heard you talk about it before?

PRINCE: My book is called When They Tell You to Be [00:51:00] Good.

It's a memoir that's out with 10 house books. It came out in 2022 when I describe it as my political coming of age.

JORDAN: It's a good

MARGARET: title.

PRINCE: Yeah. Thank,

JORDAN: we have less than a minute, but is there a favorite song that Renshaw loves to hear you play?

MARGARET: Oh no but it's not recorded. It's just piano music. He likes when I play piano.

Love that he hates when I play accordion,

JORDAN: That makes sense.

MARGARET: I know. It's like weird high pitch noises.

JORDAN: Ah, yeah,

MARGARET: yeah,

JORDAN: yeah. Dogs. Well that person. Alright, well thank you

MARGARET: so much for having me [00:52:00] on.