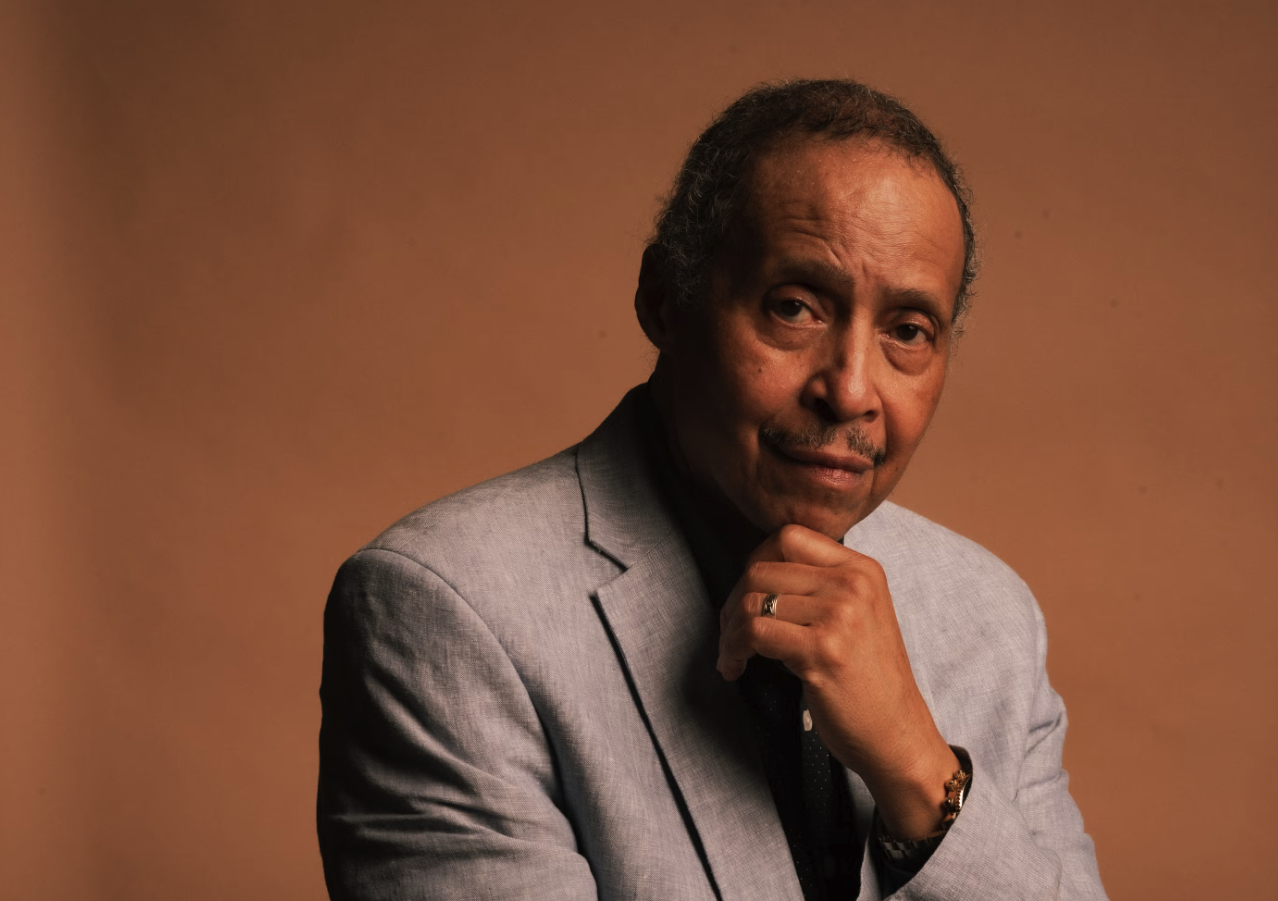

jamal joseph

jamal joseph

Listen up.

JAMAL JOSEPH: [00:00:00] The time has come for rifts and revelations for way out trips to inner space. Now, if truth is one, if truth is really one, then it must be our perspectives that are fragmented. The journeys we all make in search of unblemished realness reveals that much of the rest is a lie. And if love is to transform and to be transformed, then creativity must be the child of the most perfect union.

We may not have all of the answers, but at least let's come together and try to understand the questions through truth filled endeavors that build large creative fires and large, bold actions.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Jamal Joseph is a revolutionary writer, director, poet, activist, and educator who began his journey as a member of the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army. After serving six years in prison as a part of the Panther 21, Jamal turned his [00:01:00] experiences into the foundation for his creative and educational work.

He has been a professor at Columbia University's graduate film program and the executive artistic director of Impact Repertory Theater. Jamal's films have been featured on major platforms like Fox and HBO. He's received numerous honors, including an NAACP leadership award and an Oscar nomination for his work on August Rush.

His memoir, Panther Baby, A Life of Rebellion and Reinvention Chronicles his incredible journey and was released in 2011. Welcome to another episode in season two of the Dugout Happy Black History Month. This, I will say, is definitely one of my favorite episodes of the podcast, and it's an interview with Jamal Joseph.

JORDAN: Time and our life and our journey is so precious and it's conversations like these, not [00:02:00] only 'cause they're intergenerational, but because of how much experience and knowledge is being conveyed.

I'm excited for y'all to hear from Jamal Joseph. Think about how, I think it's one of those folks, like I also wanted to ask them about So Stray.

Mm-hmm. But didn't get to. But it's kind of like one of those figures, kind of like how you said in our so stray episode. well, it's an older black man who hasn't failed me

in a, in the revolution, in the struggle. And it's like, I wanna hold you tight and have this moment. And I feel like I spent the most of it staring in awe and being like, there's so much you can go through and still survive to be a militant humanist. Political figure in being, and I love it to see that [00:03:00] get recognized time and time and again,

PRINCE SHAKUR: I was very moved by the whole conversation and we'll share some afterthoughts.

but for me it comes at the end of a really fucking intense year. Like, what the hell? I just really admired Jamal, and especially his writing. because when I was working on my memoir, his book was one of the central texts that kind of let me know, okay, here is a version of what it's like to write about being a young, politicized black body in this country.

Thank you for being on the dugout. I definitely have thought about like our conversation during my New York book launch and then like conversations we had after. And one of our intentions, I guess in the next year for the podcast is to really dig in and, I don't know, talk to more folks, try to talk to people that have different kind of histories in the movement.

and so I definitely wanted to sit down and talk with you. First question that we like to ask folks is, could you just kind of talk about your childhood, what [00:04:00] young Jamal was like?

JAMAL JOSEPH: I'm of Afro-Cuban descent, was conceived in Cuba. mom came to New York, to give birth. here's how revolutionary genes are in the family.

my son, Jed often talks about that. she was in graduate school. my dad was in the movement and, she came, home one semester break. They had broken up and she said, mommy, my grandmother, I don't know what to do about this baby. I'm pregnant, you know, and I may need to have an abortion.

the father and I, you know, it seems like we're having hard times. He is seeing another woman and I'm not quite sure what to do. My grandmother said, tell me about the father. They said, well, he's a medical student. And, an organizer. He hangs around with, these guys, Fidel Castro and Raul Castro.

Grandmother said two things. Number one, you're keeping the baby. Number two, I'm sending you to New York and to live with your auntie. Wow. [00:05:00] Okay. To have the baby while we figure this out. That led to, me being raised, my, my mom had been, a debutante in Cuba. spoke, fluent Spanish and French, but in New York in 1953, she was a brown-skinned woman who couldn't speak English.

So she put me in, what was going to be the temporary care of, people who became my adopted grandparents. They, had older siblings and parents who had been slaves. so I heard firsthand stories of slavery. Jim Crow lynching, they came to New York. Grandpa did a number of things. He was a boxer, a cab driver, a numbers runner, but they were garveyites.

And so I was raised with this. Kind of triple consciousness, this Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Cuban, but also New York City, between Harlem and the Bronx, by people from the south, who had this profound sense of race and identity and struggle. [00:06:00] they raised me. My mom passed away. unfortunately, when I was young, I was, 10 years old.

And, I got a wonderful worldview from my grandparents, especially from, from grandpa, who had a formal education that was probably about the seventh or eighth grade, but was a lay professor in black history. I first heard the names of Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglas, Marcus Garvey. From this man whose back was bent from a life of labor, in his seventies with a full white head of hair that were telling me these stories and teaching me this history.

He was also very colorful. So it's not like we was sitting down and it was this real kind of, academic presentation. It would be more like, I'd be doing my [00:07:00] homework sitting with him and a Tarzan movie would be, playing on tv and he'd let the movie go on for about 10 minutes or so and then he would comment.

So this was kind of my first, lessons in thinking critically about race, but also media studies. 'cause here's his commentary. What the fuck is that? Tell me how in the hell this cracker, This cracker baby fall out a damn airplane swing across the vine. He speak migrant lion, monkey tiger, every damn thing.

And the Africans look like they're crazy. Change the damn channel. Yeah. So it'll be infused with a lot of like his personality, his street savvy with very clear that we were Africans. This is at a time when you'd get teased in school. Africans would be teased the way we were portrayed, you know, in those tar end movies.

In the other movies, you know, three quarters of the actors weren't even black. They were white men in body [00:08:00] paint. So he kind of like disabuse this sense that, the movies were correct or that the media was correct and that the government should not be trusted, that we should understand that we were an oppressed people.

When he passed away, I was about 13 years old and was a good student, but a little bit of a adrift, I was one of these kids that was doing really well in school, but then hanging out, with the gang members and, the street Bloods, after school trying to find that Panther Manhood.

Still was going to church, still was involved in community centers, was a member of the naacp youth council. and when Dr. King was killed, it made me angry. I can't say radicalized me right away because I was angry without politics. the way a lot of young people are, the way a lot of people are, you know, there's something in you that gets mad about the stuff that's going on.

So I got real mad about it Got caught up on the [00:09:00] fringes of the rebellion that happened in Harlem. I got rescued by a group of black militant men from cops who were kind of chasing me down for no reason, and then decided that I wanted to be a black militant. And again, not fully understanding what that word meant.

I just knew that there were people like Stokely Carmichael and h Rap Brown, saying Black power. h Rap Brown was, particularly, gifted, like he was like a poet when he spoke. Breaking out with racism is, you know, rap Brown would say you've been brainwashed.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Yeah.

JAMAL JOSEPH: Where Black to funerals, white to wedding of fool cake. Cake is white cake. Devil's F cake is black cake. You know, even at Christmas time. You know, tell me how in hell, fat redneck, hunky can slide down a black chimney, still come out white.

PRINCE SHAKUR: my mom always said growing up.

JAMAL JOSEPH: right? What's going on with that? So there was a lot of identity and a lot of anger. And then I saw the Panthers soon after that, literally on television, storming the state capitol in [00:10:00] Sacramento, calling for self-defense, talking about black folks being on. And I was like, I want, 'cause you want to, if I'm going to be militant, let me be part of the most militant group on the scene.

This, I'm 15 years old and they were the Panthers and two other friends. And I went to the Panther office and as we were taking the train from the Bronx down to Harlem, I wasn't quite sure what I was getting into, especially 'cause my friends were saying stuff like, you know, when you join the Panthers there's no getting out.

It's like the mafia. My inner voice is like, no, getting out. I got a nine o'clock curfew tonight. My other friend, you, you gonna have to prove yourself to be a panther. you gotta kill a white dude. I was like, kill somebody. I, I sing in the youth choir on Sunday. we get to the Panther office and there's the Black Panther logo.

We step inside. There's all the older brother Panthers and sisters, you know, rocking their leather jackets. Some had [00:11:00] on army fatigue jackets, dashikis, Afros, cornrows Berets, and I'm just blown away. Now I say older brothers and sisters because I was 15. They were older to me. But the Panthers in that meeting were 18, 19, 21, 22 years old.

The person running the meetings, expanding the Panther 10 Point program, which is now written, I think. 57, 58 years ago. But if you read it, it could have been written last year. And it talks about, housing, medical care, community control, education, police brutality is point number seven.

We wanted an immediate Interpol brutality in the murder of black people. I'm not really hearing what he's saying 'cause my heart is pounding. I want to prove to myself, I wanna prove to my friends. So I jump up and I say, choose me brother. me. I kill a white dude right now.[00:12:00]

Old meeting gets quiet. The brother running the meeting calls me up front. We're all sitting in folding wooden chairs and he's behind this old wooden desk facing us like a large classroom. And when I come up front, he reaches into the bottom drawer. He hands me a stack of books.

autobiography of Malcolm X, Richard and Irv by Fran Fanon. So long Ice by Eldridge Cleaver. And of course the Red Book quotations from Chairman Mao. You know, all panties had that red book. I said, excuse me brother, I thought you were gonna arm me. And he said, excuse me, young brother. I just did. and then as I'm walking back to my seat, he says, young brother, I want to ask you a question since you came in here so matter white people.

He said, if all of these pig police that are in the community, realizing people, beating people up, blocking people up, shooting people down, if they were all black and all the victims of police brutality were white, [00:13:00] he said, these slumlords buildings that are falling down, rats and running up and down the hallway, no heat in the winter, all of the slumlords were black.

And the people living like that were white. Would that make things correct? And I said, no, sir, it seems like it would still be wrong. And for the first time he smiled, he said, that's right, young brother.

This here is a class struggle for human rights, not just a race struggle for civil rights. Study those books so you can understand what revolution is about. And one last thing, there was a poster of Che Gura on the wall, and there's a quote from a speech that Che gave at the United Nations United, and the quote was At the risk of sounding ridiculous.

Let me say that. Revolutionaries are guided by great feelings of love. So my head was spinning, my world was turned upside down and was within 15 minutes of walking to a Panther office, I started to [00:14:00] have a context, of struggle and approach to revolution that not only shaped my experiences in the Black Panther Party as political prisoner, prisoner war, the BLA, but to this day about that approach to struggle, understanding the real foundation, what we're fighting for, and understanding key utmost that we need to be guided by great feelings of love for the people.

JORDAN: You mentioned how the assassination of MOK wasn't like the radicalizing point and how this attachment to the politics and the power analysis, what points. Or times or stories can you think of, of when you're moving through this 10 point program and like the history and you're feeling it and you're organizing, do you feel like was like radicalizing you or moments that, [00:15:00] because I feel like I'm constantly radicalized, so like things that are like kind of a theme and when you feel, yeah, I mean the power of, well,

JAMAL JOSEPH: I think the radical anger, happened when Dr. King was killed. I think the political education, so that context to the radical anger, right? So that's why you see me separated just a little bit happened that first day in the Panther party and everything was kind of built on that idea of service to the people. Political education was, and political education classes happened several times a week.

And you were required, to go to at least two political education classes a week and to do community service. By the time the repression, started to increase on the Black Panther Party, you were required to go to political education classes and meetings every day.

And a lot of Panthers left home and lived [00:16:00] in Panther, what we call panther pads or panther communes. PE could look like working through the autobiography of Malcolm X. Certainly it would pe classes that were about the Red Book, but there'd be days where political education classes would be the New York Times or the Daily News so that you could read something that they had written and learn how to analyze it or as we called it, break it down and speak to that.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Yeah.

JAMAL JOSEPH: So that you weren't just in, you know, what we call these days. Just an echo chamber. this is what taught young Panthers how to think critically so that when you went into the communities whether you were on the street corner talking to brothers and sisters or if you were organizing on a college campus and you got into a debate, with an economics professor, you had some context that you could speak from.

And then as I was with Older Panther leaders, you know, shadowing them, it would be amazing to see that. [00:17:00] It would be amazing to see people liked Aruba, Ben Waha or Michael Set Tabor, or Feni Shakur, who became my big sister right away. 'cause she tried to send me home and tell me not to come back. You know, I was too young.

PRINCE SHAKUR: that.

JAMAL JOSEPH: Yeah. it would be amazing to be with them during the course of the day and see them being able to talk to hustlers on the street corner. Grandmothers who were struggling to keep food on the table for their families, for their children, and for their grandchildren, and a political science professor on the campus of City College or NYU and Columbia, and be able to talk to all of them and be able to code switch, you know, reminded me of that moment that, Alex Haley describes being with Malcolm X, that he was on the street corner.

Malcolm was speaking slang and organizing the folks on the street corner in terms that they could understand. But to see him on a college campus and, be able to talk about the issues, as [00:18:00] someone who had a doctorate in political science, to me, I learned that's one of the keys of organizing is being able to kind of communicate and so that the political education classes dealt with all of that.

and it's what made. I think the Black Panther party both a threat and effective is that we did have leadership, we did have, national leadership, state leadership, local leadership. But when you were out in the community organizing Panther papers, everyone could kind of speak to the issues and you know, as we say and break it down and riff and rap and talk to folk.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Thank you for that. 'cause I think one of the questions we kinda had or were curious about was yeah, how exactly the party led education or what that looked like So I feel like that's super helpful. another question I kind of had was, could you talk about the process of you getting deeper into organizing with the party?

'cause I know that from previous interviews you've done, you said at about the six month mark of being in the party was when the Panther 21 kind of case started, [00:19:00] I believe. And in that time, I think you noted that you were leading a lot of the organizing around high school students.

So could you talk about that period of time leading up to kinda when Penn or 21 happened and How you were kind of taking in these lessons from these other organizers and what in the stuff that you were doing?

JAMAL JOSEPH: the other key part of one's political education was going to work right away, being put to work right away.

one of the principles of the party was that all theories based on practice. So you couldn't just show up to political education class and just be really articulate and be good on the issues. You couldn't just be a theoretician.

it would be, you know, where were you? I didn't see you at the breakfast program. I didn't see you when we were, across the street helping lead the wrench, strike Not only organizing the tenants, but fixing the broken windows and painting and covering up the holes in the ceiling so the rats can't just [00:20:00] run over the building.

one of the best compliments that you could get in the Panthers is that you were a good worker. It meant that you were doing the breakfast program at the welfare center, selling newspapers, being the person picking up the clothes from those dry cleaners that were donating to the free. Clothing program, all of that took work.

And that was the best compliment. That not you, that not you with the kind of, you know, most articulate, not that you were a badass, that when the police did come, got in their face, but the best compliment is that you were a worker working in the community. So most of what I know about that kind of organizing and about leadership that, that, evolved and came with me throughout the life was for, was around those organizing principles, right?

Meeting the people at the point, it's what we call having a face-to-face relationship with the people. and that meant the people knew who you were because they saw you [00:21:00] in the community, not just in front of the, the Panther office, you know, on a bullhorn when we'd have those community meetings, but you were there when,

When someone wasn't getting medical attention and you helped get them to the hospital. And then once they were at the hospital, there were community folks and other people in the Panther party standing there demanding immediate attention for that person, whether it was a grandfather or grandmother having a heart attack or a kid, having a sickle cell anemia crisis.

which we become faithful because my oldest son was born with sickle cell anemia. The fight for sickle cell anemia, I first learned about in the Panther party moments like that when we were in the emergency room demanding that a child get treated and get pain medication. And then the follow-up was a national sickle cell testing program, which, most medical professionals will tell you is what brought, awareness about sickle cell anemia to the country.

Right.

JORDAN: Yeah. That was one of the most [00:22:00] powerful moments in the book that I was like. This is mutual aid, this is direct action. This is community organizing and deepening relationships at a local level and the things that can be replicated.

JAMAL JOSEPH: Absolutely. And that's what happened. This is really an important point, is that people came out to help run those programs.

It was community folk that would come out, that would volunteer, that would bring in donations, that would donate their time. It's why these programs outlasted the Panther Party. And you know, as Sister Erica Huggins, who was a Panther leader and was a political prisoner, said, we shame the schools and the government into doing these programs.

So, you know, a lot of people said, inspired by, she said, shamed by the Panthers to say we could do it with no money, You know, but then we would use that to educate the kids, you know, to educate the families to say, [00:23:00] how is it that, you know, we have a government that can spend billions of dollars, putting a man on the moon, but they can't spend whatever it costs for a plate of food those days, 25 cents, 50 cents.

You can't figure out how to put a plate of hot, nutritious food in front of a child, you know, a black or brown child. and then those programs were picked up by other organizations. So, you know, you had the Young Lords, you had Harmonious Fist, you know, from Chinatown.

So they, they, they were doing food programs. They were calling for testing. You know, in Chinatown the issues were tuberculosis, po folks living closely and getting kind of community folk involved. So. That was the true spirit of organizing. One of the greatest lessons that I learned about organizing was from Afeni Shakur when she said, Jamal, the goal of the Panthers is not to have every man, woman, and child, you know, sister, brother, he, she [00:24:00] or they, and the black community become Panthers.

It is to teach people the possibility of struggle through example. And if we do our job, we make ourselves obsolete. You won't need a Black Panther party because the whole community is organized. The whole community is revolutionary. And that goes back to one of the other, organizing points and sayings.

Let the bakers bake, let the teachers teach. Let the builders build, let the healers heal, but let them do it with a revolutionary consciousness.

JORDAN: Every cook can govern.

JAMAL JOSEPH: but Prince, to go back to your point, because I, I was around so much, you know. you know, first became the kid that didn't go away and a little bit like the mascot, but then brothers and sisters, you know, took me with them so that I could learn.

So I got promoted and elevated. but that put me in the crosshairs of the District Attorney Frank Hogan. When he, when, when he was organizing the Panther 21 case, you know, [00:25:00] Panther offices were being raided, blown up. Panthers were being arrested. None quite as horrific as what happened to Fred Hampton in 1969.

But Frank Hogan said, well, I'm gonna deal with my kind of Panther problem situation a little bit differently. I'm gonna use the power of the district attorney's office, and if I arrest all of the leadership, you know, if I cut off the head, the body will die. So everyone who was an officer kind of got targeted in that Panther 21 case.

So I was an officer. I was 15, but I was still an officer and I kind of, you know, fit into that profile, which is why I was arrested. on that, that fateful morning in 1969, April 2nd, 1969, it increased across the country. There were bombings. There was of course, in December of 1969, the murder of Fred Hampton.

And then a few days after that, there was the raid on the LA office, which was, the first mission of swat, you know, special weapons and [00:26:00] tactics was against the Black Panther party. That was the SWAT team. Wow.

JORDAN: Yeah. Oh, wow. Yeah, it's just, that just brings me back like so many of the, some of the biggest creations for domestic military forces from the state come from and are directly like some, most of the time, a rebuttal too.

The revolutionary forces of folks, whether it be like even the invention of the FBI, 'cause world leaders were being assassinated in Italy and attempts in America. and even just having that sort of political fervor was enough to get the machinery gunning for you. And I mean, they still still do and try.

what did you do, do you remember from like the legal support and what that experience was like and how that's maybe impacted or [00:27:00] things that you've seen legal support change or how that organizing has evolved?

JAMAL JOSEPH: Yeah, it was surprising to me the kind of support that came about. I just wanna make one point about what you just said.

You know, when J Edgar Hoover, testified in Congress, about the Black Panther Party, he said the Black Panther Party was the greatest threat to the internal security of America. And he was getting congressional approval that if this is the greatest threat, then you have to give me permission to handle this threat.

And it's going to be a program that I'm not gonna speak about in this congressional hearing. But those of you who are on these special committees are gonna fund and allow me to do this thing called COINTELPRO the Counterintelligence Program. the thing to understand about the counterintelligence program is it wasn't [00:28:00] just good old fashioned police work.

Let me put the Panthers under surveillance and go after them if they're doing something wrong. It was counterintelligence, it was to destabilize, it was lies, it was phone calls, it was letters, it was agent provocateurs, it was undercover cops and FBI agents to destabilize the Panther party, which leads to the Panther 21 case.

But here's the important point to remember in all of this. Diego Hoover hated the breakfast program more than he hated the self-defense program, more than he hated in those cities that were legal, where panthers were patrolling the police with legally possessed rifles and shotguns and law books, because he understood the power of that kind of organizing.

He understood radical history in a way, better than we do. Let me give the Cuban revolution for an example. when Batista's troops would [00:29:00] move in and they had to abandon a base, they found, what did they find at the base?

Some weapons. Most of the weapons were going, they took it with them, but they found schools and clinics wherever they went, they found schools and clinics, outdoor schools, clinics, because when the rebels were secure, the revolutionaries would secure something. They understood that they were there fighting for the people.

And the best way to organize the people is to show them that we, this revolution is gonna do things for you, that the government is not doing for you. And so, and that's why one of the first mandates of the Cuban Revolution, when you look at it, was to end literacy. And infant mortality.

Cuba still leads the world. They have a higher infant survival rate than we do here in the United States, especially in communities of color. So that when we would read when [00:30:00] was happening, and get a chance to meet folks who were from Cuba or travel to Cuba, these were the lessons, not just the theories, not just the quotations from Chairman Mao, from Cha Gura or from iCal Cabron, you know, from all of these great revolutionaries.

What were they doing on the ground? That's what we had to do in the community. In fact, when you left the Panther office, you would say to people, I'm going into the field to organize. When we would go downtown, we would say, and we would say, well, where are you gonna be in the colony? Or the mother country?

We'll say, going in the mother country, maybe you were gonna go to, you know, 42nd Street and try to sell some papers and organize some folks. So those lessons, right, and what I'm hoping people take away from this conversation is that it's gotta be so people centric. If you wanna study these struggles, you have to see what the people did in those poor, in those poor towns, in the mountains and in the jungle to organize folks.

And that is around their [00:31:00] needs. And then you politically educate folks, and that's why you build what they call popular support. That's why part of why the No Panthers were killed in the LA Shootout was the brilliance of Geronimo Pratt, who built up the defenses, the defense system, and sandbags and trained the Panthers.

Geronimo Pratt was Deputy Minister of Defense. He was a Vietnam veteran, but also those community programs that when the police were, were doing that shootout, which lasted for about 13 hours. The whole time people were on the streets behind barricades watching, saying, don't you murder those panthers?

Don't you murder those comrades, don't you murder? and the grandmothers are out there. Don't you murder those children? Those are my babies. I saw them grow up. Or if they didn't see them grow up, they feed like my grand babies. Right. So I want to, kind of come back to that now for the Panther 21 case, the core of that were people part of [00:32:00] an elite police unit called the Boss Unit that infiltrated the Panthers, that became members and leaders.

Right. And they were the ones that would bluster and that'd be the most radical. And said, you know, when a tenant. Would come in and said, we need help in this building. When a group of tenants and, you know, Afeni and other people who attended organizing would say it's gonna be a rent strike.

And then we're going to have people have lawyers to volunteer to set up escrow accounts and we're gonna make the repairs. We will be there to stop the eviction, but we're going to, you know, be able to show where the money went, what the landlord wasn't doing. And you get someone like a Yah who was an undercover cop that would say, you know, listen, we're revolutionaries, let's find out where the landlord lives.

And drag him from his house and put him on trial, a public tribunal in Harlem and lynching and stuff. And of course we would be like, yeah, you know, the younger, the younger brothers would be like, yeah, let's do that. You know, [00:33:00] and someone like an Afeni Shakur would say, and then what happens to the people?

And then what happens to that building? We're inviting repression, we're inviting that. So those, you know, but that's what the agent provocateurs would do, and that's what the counterintelligence program is about.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Our podcast is a tool for learning, and we're taking it further on Patreon by supporting us yo gain access to exclusive reading episodes where we unpack key texts and ideas, plus early access to interviews with radicals and revolutionaries.

Your contribution helps to make these resources more accessible and impactful. Visit patreon.com/the dugout pod to support our work.

JAMAL JOSEPH: What I like to talk to young activists about is that, so they would do phone calls, they would do letters, they would have people in the meeting not just to observe, but to urge people to take radical action.

That [00:34:00] could be the cause for arrest, or could be the cause for a raid, or could be a cause. for someone to be assassinated in those days, you know, they would, have to send someone in to infiltrate. They would, in some cases get you know, if they were gonna make a court case, have to get wired, tap orders from a judge so that they could place these listening devices.

Now all they have to do is just turn your phone on in a meeting. And now we get into these heavy debates. Prince, you and I talked about this at you, at your book lunch. You know, we will get into thinking that you're in a heavy ideological debate with this comrade that lives in Seattle, Washington, or Miami, and you haven't seen them, don't know them.

How do we know that, quote unquote, comrade is not sitting at some CIA, terminal in Langley, Virginia? YFBI headquarters in Washington DC So when we [00:35:00] talk about the takeaways, I say I wanted, I like to talk about the community program in that aspect, but the destructive nature of the counterintelligence program and will it be five or 10 years from now?

Will we know the name of the new program? And when we see how many of you know of our, our family, our comrade family, went to prison, was killed, or. You know, got, got so depressed that they had to kind of leave the struggle. So their lives were ruined in, in other ways. You know, there's other ways to ruin lives than just assassination, imprisonment.

You know, you can cause someone to have a dissolution of their family, their mental health, their physical health, all of these things. So it, it, it's, it's all stuff to kind of pay attention to when we try to look at the lessons of that period. Jad and I are working, my son Jad, are working on a documentary about the Panther 21.

Gerald Lort, who was lead counsel, talked about the challenges of that case that [00:36:00] we, and he used it in, contrast of the Chicago seven case where they were anti-war leaders. They were well-known in the Panther 21. We weren't known. We were known in the community, but not nationally known.

Bail said at a hundred thousand dollars, no money, no support. And Jerry went to a couple of students who were anti-war, organizers, Columbia students who he had represented for free saying, I need help organizing. And they built a Panther 21 defense committee that was amazing. Students were involved.

And the other thing that they did was that it was a broad-based coalition. So you had originally predominantly white students, but then city college students, and then community folk, and other folk. And they were pointing out that here are men and women from the community who certainly can't afford a hundred thousand [00:37:00] dollars bail because who were the Panthers?

Who were the Panther 21? Students, workers, welfare mothers, former street people. A couple of people who had been, formerly incarcerated folks, veterans. Curtis Powell, who was a biologist but no one had a hundred thousand dollars and, which is about $900,000 in today's money.

I first, started to understand the sophistication of what was going on when I had been in prison for about three months. And they brought us all together in court. 'cause initially they separated all of us so we couldn't communicate. So it wasn't like the 21 was all in one jail. Afeni Sha and Joan Bird were in the women's house of detention.

Myself and a panther named, Alex McKeever. We were on Rikers Island, but even on Rikers Island, we were separated. [00:38:00] So when we'd have a court hearing, they'd have to bring us in from all different points, and then we'd have that court hearing, and then afterwards we'd all be in a large cell conferring with our lawyers.

So I just knew that we were having a bail hearing. And beside our lawyers, they were lawyers from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. And I was like, what is the NAACP doing here? And the NAACP Legal Defense Fund was there because they believed that we were being prosecuted and persecuted because of our political beliefs.

And even though the NAACP obviously had different beliefs, the mission of the defense fund was to look at arrests that were racially motivated because of race and because of someone's beliefs. This blew my mind. It made me understand the sophistication of real organization. Bring people around the [00:39:00] issues.

Yeah. We, in turn, made bail an issue for everybody that was being held. So there was a rebellion. Afeni was bailed out. I was bailed out, and the Panther leader, Duba Han had been bailed out. The remaining panthers we had by this time won a motion to all be housed in one prison, which was the Queen's House of Detention, or called Branch Queens in Long Island City.

And the Panthers led a rebellion taking over that prison. It wasn't the typical, we want better food, or we want more time, more recreation time. Number one demand was bail hearings and judges were dispatched. To that prison to have hearings in the prison visiting room. And about 30 men were release that day and it happened similarly.

Wow. So this is how you can take an issue and organize around it. [00:40:00] We made this an issue in the courtroom. We made the issue of jury selection, which was one of the points in the 10 point program. We wanted, a trial by a jury of our peer group. And when we would say we in the 10 point program, it wasn't that we, the Panthers, it was like we were recognizing that historically people were arrested and tried and convicted by all white juries.

So the point, I believe it was point number eight, we want a trial by the jury of our peer group, and we define that as someone from your same socioeconomic, and racial background. We made this a big fighting point in the Panther 21 trial. We talked about all white juries. We talked about that when we were doing the voir dire process where the lawyers get to examine a jury.

We would say, do you know that there was an organization called the Ku Klux Klan? Do you know about people who were legally lynched? And, the jury selection process, which usually just takes [00:41:00] a day or two, you know, sometimes just an hour or two in a criminal case. Our jury selection process was, was a month.

and it's because we wanted to make everything a fight. We were convinced that we would be railroaded, that we would be legally lynched for why we were here. And this is why Afeni Shakur said, I wanna represent myself to be able to speak directly to the court and to the jury,

we wanted to fight to show that our trial was illegal lynching, but it was representative of what was happening all across America. The amazing thing about this is that we seated the most diverse jury that Manhattan had ever seen. Now, you go to a jury in Manhattan, you know, you're gonna get a diverse jury.

But then juries were mainly white men. And when we talked about these issues of self-defense, yes, you know, the police, when they raided our apartments, found weapons in every apartment. Do you understand why? Because of police [00:42:00] terror, because of the history of the Ku Klux Klan slave patrols. Why black people feel that they have to defend themselves and protect themselves.

So we made that a repeated point. We talked about community programs. What we didn't realize in the Panther 21 is that because we had selected the kind of jury that we selected, they were actually listening to what was going on. So to everyone's surprise, at the end of the trial, which lasted. 13 months and the whole procedure was from the time the Panther 21 was arrested until the verdict was two years that the jury found, the Panther 21 not guilty on every count.

JORDAN: Yeah. and you say you think that has a lot to do with like the putting up a constant resistance during every single part of it. Whether or not did you think that [00:43:00] you were gonna win or that there was that much of a chance at winning at all? It was just fight.

'cause there's nothing else to do. No.

JAMAL JOSEPH: For us, the victory is that, that is that we had this defense committee that we knew had become a model for resistance because when you look out in the courtroom, there was those white students. There was, folks from the anti-war movement, from the women's movement, for what was called in those days, the gay liberation front workers, folks from all communities, black, brown, red, yellow, you know, the Panthers, greeting was all power to the people and you know, when you were doing a political education cast or rally, people would say right on, and then you would, you would break it down.

That means black power for black people, white power for white people, red power for red people, brown, powerful brown people, yellow, powerful yellow people. gay power to gay folks. Workers, power workers, and you understand that that's the United, United front that you were [00:44:00] building. So when you looked at the Panther Defense Committee, that's who you were seeing when we spoke, when Afeni and I got out on bail and other people, we, we would, you know, we'd be at rallies or we'd be at, there was a organization called the Committee of Return Volunteers.

These were Peace Corps volunteers who had come back and that committee became Panther supporters. They were Quaker organizations that supported the Panthers, and it's not they agreed with everything. most people saw the 10 point program as something that they could agree on. But we were a revolutionary Marxist organization.

We were calling for class struggle class warfare. The abolishment of the capitalist state for people's government. But there were people who said, I don't know if I'm behind all that, but I can get behind the idea that everyone deserves medical treatment and that police should not [00:45:00] be, you know, the armed assassins for the state who were able to connect anti-war kids with the idea of if you believe that there's a war of aggression happening in Vietnam, then you have to see the war of aggression happening in black communities.

So it radicalized, but then we were able to come back to our communities sitting with folks from these other, movements from these other organizations and organize around that. You know, when you see the anti-war kids, don't throw rocks at him or tell 'em, get off hundred 25th Street because they're, they're fighting the same battles that we're fighting against state terrorist, state murder.

you bring what's, what, what, what you're learning in the women's movement or the, you know, you know, or the GLF, the gay Liberation front to talk about. We gotta talk about what's happening in the black community and that some of our, you know, some of our great leaders, you know, great civil rights readers, great revolutionary leaders who, who were [00:46:00] and who are queer.

So you are able to kind of talk about that. There's articles that you can go back in the archives and see that Panthers took a position of that, not only in meetings, but in the Black Panther newspaper to talk about that. So the idea of building a united front when the Panthers in the days before the organization was really kind of forced to shut down all of the officers.

So many, Panthers had been killed, were underground, were in prison. Two things I want to point out. It was the women of the Black Panther party. That helped, helped the Panthers last as long as it did. There were times that you could go in to Panther offices and that it was entirely staffed by women.

But because these sisters were such great leaders, so strong, it probably didn't hit you in that way, but that's what it, what was happening. Other thing is that we stopped opening Panther officers and we were opening what was called [00:47:00] United Fronts. Again, a united front against fascism officers. This is why some people think they were white Panthers, you know, that they were Asian panthers.

'cause they see people coming in and outta those offices because we realize that's the most important organizing that we can be doing now. is build a united front against fascism. Malcolm X talked about it in his speeches.

Dr. King talked about it, the Panthers talked about it. Instead of fighting about the 10 things that we don't agree on, let's come together on the three things that we can agree on and organize around that.

PRINCE SHAKUR: yeah, no, that's so extreme. It's just, that's literally something I've been thinking about a lot lately, especially post-election and how there's so many feelings around who did what and why and who failed who.

I appreciate, especially to your legal defense point, I mean, here in Ohio, this past year, I've been helping out with a lot of legal defense for This case related to [00:48:00] five people that were arrested for doing a work stoppage at a Boeing facility related to their connection to Israel.

And in what you're talking about it. 'cause it's, you're talking about the black, the party being able to build a base across what mutual aid and resources they were able to offer the community. So when it came time for a legal campaign to happen, it didn't just come out of thin air.

Which I think is something that me and a lot of comrades here have been kind of struggling with. Like, if we can create a legal defense structure, like what is that tied to that actually can like build community support And then even to the point about like a lot of people left their lives theoretically, or their jobs or other things to join the party or to work in it significantly.

it's people really worried about their jobs and getting back to their lives. And not to say that that isn't, reasonable, but I think the process you're describing to me is looking for a more total political life.

So when these challenges come, there's that united [00:49:00] front to get the work done that's necessary.

JAMAL JOSEPH: I have a good friend, David Fenton, who, I met, he took, he was this white kid with the camera. I met him, oh my goodness, 55 years ago or so. he was working for Liberation News Service, which was kind of a radical news outlet.

They'd get stories and anybody could print them in, you know, whatever they were doing. So that this picture, on the cover of Panther Baby, he, he took that photo and David then went on to. organize a no Nukes conference and, fight for different kind of political prisoners. And then he built a very, successful public relations firm, only taking on causes that he believed in, you know, but we, and so now we're both in our seventies, we were talking about, prince, to your point, it was easier to be a full-time organizer in those days because it was cheaper to live.

So you could get an apartment in Harlem [00:50:00] for a hundred dollars a month, or in the village for 150 a month, right? eight of you could live there. Everybody could kick in. Maybe one person had a job or people had a couple of part-time jobs. You could stock the refrigerator, like literally for like $60 a week, $75 a week, and you could be a full-time organizer.

So the capitalist debt system, right. things being so high. And then what happens with the marketing that you have to have this to be really comfortable. So everybody has to have the latest this and the latest that. And then you have to subscribe to, you know, you've gotta have your internet connection and you have to have all these things.

so even if you have a job, you're part of the working poor, right? And so everybody, even if you've got a different job, is two or three paychecks away from being homeless. So it's hard to be a full-time organizer. [00:51:00] Now, what do we do about that? This is where when you look at kind of multi-tier organizing, right?

And when you look at going back to the Cuban Revolution, they had their above ground kind of organizing that they did that, that always kept it going. They had their bases where they were working with working class, but also the farmers and the peasant class, organizing all those levels. Some of our quote unquote progressive millionaires, you know, why don't we have housing that, and grants and fellowships for full-time organizers, and not just around the issues that you kind of believe in, not just your pet peeves, right?

I can throw two or $3 million of my personal money into liberal politics, into a failed, presidential campaign that was kind of doomed from the start. But I can't come up with that money just to say, what if I created an endowment that [00:52:00] identified some of the best organizers who can organize around policy?

This is something that I think, we can learn from the movement that came about from the AIDS epidemic, where you had people that were organizing around policy. You had people that were organizing a community, you had people that were organizing around needs of folks.

Look what happened within that movement, right? You had people, there's a CNN episode from the eighties, you know, how they do their different things. this is an episode that organizers should look at because it shows you how people who were successful and rich, like the, the guys who had been, they, who were, who had been publicists for Madonna, left their jobs to bring all of their skills toward AIDS activism.

At the same time, you had folks who were good at food distribution, feeding folks, medical stuff, making, available [00:53:00] someplace where someone who was infected fighting the disease could get a meal, could get medical treatment, whether they had insurance or not. Housing compassionate care.

This is one of the best examples, you know, since that time, since the sixties that we, that the Panther Party did of what multi-level, multi-tier organizing looks like. So if we can reflect and if we can look at best practices from the abolitionist movement, which was, if you look at the multi-tier level of the abolition abolitionist movement, who was there?

Right. White people of good conscience, free freeborn, black folks, former slaves, Harriet Beaches au, who was the bestselling author at the time, right? That Uncle Tom's cabin was radical and it was a bestseller. Prince, you and I wish we had these numbers with our books. The way her books, the way her books sold, lost her son, who she urged to join the [00:54:00] union who died in combat.

So if we could start looking at best practices from how people organize and the multi-level organization, that's what it needs to look like today. There's a generation of P. If there was that kind of fellowship, here's some housing, here's a food stipend. We need you to be full-time organizing and we need to organize yes, around policy, yes, around education, but here's how we organize.

Grassroots, right? So we're not just paying attention to a black kid when they've been shot or when they've been falsely incarcerated. We're creating these kind of education, nutrition, community self-defense programs, awareness programs before that happens. And these kids themselves can be the organizing the advocates for their peers.

They can be that community watch, they can be those legal aid warriors, even without, you know, law degrees, right? And then understand that before you go to the courtroom to advocate for this person that's not famous because they're a [00:55:00] political prisoner, but they're political prisoner because of the system that you've gotta stop at the breakfast program.

You've gotta do that time. That's what you get your breakfast, then you go to your assignment, then we debrief. The lessons are there for us historically, but we've gotta get out of these silos and not be talking to. People in other areas, but also talking to each other from the bottom to the top. Or as Bandini Brown used to say, Muhammad Ali's, in his camp.

Let's, let's organize from the root to the fruit.

JORDAN: What, as like the organizing scene without like a central party, like the Black Panther party, you've taken your political endeavors to youth mentoring through doing community activism and meeting people where they're at with skills that you have and growing and connecting with people from there.

What kind of approach do you feel like you found [00:56:00] useful to make sure that it's not siloed and that it's even in this age, a continued political process and building that revolutionary movement and relationships with the folks that you're around?

JAMAL JOSEPH: So when I was in prison the last time I, I was in prison, when I was young in the, you know, of, of the Panther 21 case.

And, subsequent a BLA case where we were shutting down drug deaths in Harlem and the Bronx at gunpoint. So even if it's a drug dealer and you're destroying the drugs and giving the money to community, the organizations, it's still armed robbery. So, but my last time in prison was part of a case that was known as the Brink case, and which a group of black and white revolutionaries were accused of, robbing a couple of brink trucks, but also freeing, a side of Shakur and other [00:57:00] political prisoners.

And I wound up. Not being convicted of the main charges, but of being, helping to run a modern underground railroad and helping people who were on the run from the FBI evade the FBI and get out the country, which is a law called being an accessory of the facts. So even if you're not part of the main action, when I got to prison, I thought, so many comrades that I knew had been killed or were doing life in prison.

And I thought we had, and I went through a period of post-traumatic stress. I thought we had failed. And even before I came back to prison, last time I went through periods of, I was living in the village, I was doing some acting, I was, had a small kind of limousine business, but you know, I was using drugs, I was self-medicating.

And while I was in prison. I [00:58:00] was compelled by some of the other guys to start this theater company 'cause they knew I had done liberation theater, activist theater. And then quickly other men started showing up. other prisoners started showing up and it became this multicultural group.

And we would share as we were developing the pieces. And I was sharing from a point of, you know, sharing my depression and sharing my guilt for, you know, the people that had been killed, had been a leader. So sometimes it was some of the orders that I gave that may have wound up, you know, causing people to wind up in a situation where they did get arrested or they did get hurt really badly.

And Ernest Jennings, whose nickname, Was Nitro 'cause he was a demolitions expert in Vietnam. Great actor, crazy, crazy, funny brother, madly talented. And [00:59:00] he said, you've got post-traumatic stress. We were taking college courses and sure enough, out of about 15 symptoms, I had like 12 of the symptoms.

And I was able to kind of start self-healing through the theater and start realizing that my life was a continuum, right? And that it wasn't over. It's only over when you give up. And then I saw the power of the Theater of Arts and that kind of organizing. So I made the decision then that I wanted to use the creative arts as a weapon, but there were certain other things that I wanted to bring along wherever I was.

Number one, I wanted to talk about the counterintelligence program and I wanted to talk about gossip, and I wanted to talk about that kind of division, how we can spend so much time. Looking at what we're not doing right. you know, or, or saying what we do do wrong, we can't figure out the rights. What are those things that we can organize around?

And so I kind of consciously didn't align with [01:00:00] one political organization because I wanted that space to be a safe space where anyone could come and hang out in the workshops and be part of it, especially the youth component, but that the adults that I could be in conversations with, people not holding one kind of political line, but that line, that is, you know, at the risk of sounding ridiculous, revolutionaries are guided by great feelings of love.

I keep the word revolutionary in there because I'm still a revolutionary. I want to be judged on practice. And if we can have good practice, then. If we're in an organization, not in an organization, in a committee, not in a committee, that can kind of be our guided in our North Star. So that's been the work and what I've tried to pursue in, you know, my youth work and my creative arts work and kind of the organizational work.

And so that's in the 36, 37 years that I've been outta prison, kind of been, been the [01:01:00] focus somehow stayed clear of those kind of debates that I think are gonna be divisive and not be kind of the bigger picture. I think when we look at the environment, that there's plenty to talk about when we look at, you know, the prison industrial complex and the carceral state, there's plenty to talk about when we look at health disparities and health dep.

There's kind of plenty to talk about when we look at, you know, the police state and the military state. So what are our ways in to do it? For me always. And how can we find the community connection about that? You know, in Cuba, again, to use the model of the Cuban Revolution, post revolution. Everybody had to cut cane.

Everybody had to know cutting cane is the hardest stuff in the world, but the different ministries, and it didn't matter if you were a doctor or a lawyer or a professor. You went out, you know, for a couple of weeks each year and you cut cane, not just to help sustain the national economy [01:02:00] so that you could remember this is what the struggle is.

The struggle is from all of us, from the least of us to the most of us. And nobody is the least in the most if we're all fighting together. And if we're all fighting around those and organized, rising around those three or four things that we have in common, instead of, wasting time.

On those 10 things that we can't agree on.

JORDAN: I wanted to ask if you had any reflections on KUWASI BALAGOON and their impact or how any relations or stories from having that sort of relationship?

JAMAL JOSEPH: Yeah. KUWASI brilliant poet.

I think Kuwasi always lived life on his own terms, you know, and fought and was, was, was willing to put it down. And I think as someone who had a trans partner, you know, that, that [01:03:00] and, and, without. Saying too much or getting anybody in trouble. His partner was down. You know what I mean? So some of the, some of the spaces and places that we met with, it wasn't just like we met, we, it wasn't just like we met in some club at the village and quasi went, oh, by the way, this is my partner.

But because of Kuwasi, he's practice and because of what his partner's practice was, it was like, you know, let's try to get through this day. Let's try to accomplish what we need to accomplish and kind of keep it moving, you know? Yeah. But a great poem, oh my God. KO's book is a book called Black Fire and KO's poem is better, what is it called?

Better Off. And he's talking about racism and the oppression. He was like, you know, better off dead than Alive if you love them. Wouldn't you like to see them better off?

PRINCE SHAKUR: I think we just have like maybe one or two last questions and this is kind of because I [01:04:00] really appreciate everything that you're saying 'cause I think even you mentioning PTSD, like I can notice it in so much of what so many people I know have experienced this year. And I feel like a big question a lot of people I know are asking themselves, like working through that disillusionment or working through the ways that we feel like we failed.

What would you say to organizers that are like now kind of more afraid or disillusioned because of the political moment that we're in, if anything at all

JAMAL JOSEPH: So it looks like the big battle is over. It's not because we're here and there's still. more of us than them. And there are, there's the opportunity to organize folks around their needs. There is, on YouTube, if you Google Bob Lee organized a Black Panther leader. There's this great video clip. Bob Lee was a Fred Hampton protege of him [01:05:00] in a poor white community.

And you think he's like in the south, in Appalachia or Alabama someplace talking to poor white folks and saying, what can we do? How can we help you organize? but actually it turns out that it's West Chicago. And when they went in, there was actually a confederate flag hanging outside.

That is so moving in terms of what has to happen when you see this teenager, this shy girl who starts to talk about police brutality. When you see this young white kid who gets so worked up that he's talking about attacking the police and the Panthers have to calm him down, right? And then at the end you start to see some of these white organizers saying, we're going to go March for jobs.

That is so inspiring, talking beyond ourselves. But the Panthers did go into that community because they knew they had something to talk about because they knew that there's stuff going on in poor [01:06:00] communities, white communities, brown communities, red communities.

There's disease, there's hunger, there's brutality. So if we can organize and organize means this person showed up, this person just didn't show up and talk about, isn't a shame that you're hungry. They came up and going like, isn't it a damn shame that we're hungry? I brought some food. Let's eat and figure out what we're gonna do next.

Let's figure out how we can all eat from the same pot again, and let's figure out how we can at the same time fight the system that is having our children go to bed hungry every night. There has to be programs.

There's nothing reformist about helping people eat, have shelter, and good medical care. In fact, it's hard for someone to hear about. A lot of political ideology in their stomach is growling. That's how the breakfast program came about. We were like, boy, they talking about black kids of fidgety and they can't learn.

the arithmetic [01:07:00] teacher is saying three apples plus two apples equal five apples, and that child's stomach is growling. Of course, they can't learn. So when you start connecting fundamental needs, but they see you are doing something about it, not just talking about it. That's why I'm saying policy.

Direct action grassroots around people's needs, you know? So I really can't say that enough. I think people can almost say, guaranteed, when Jamal comes, he's gonna be talking about these issues. And by the way, for strategies of what are we gonna do when we start winning the victories?

Are we gonna keep talking about it? Or because we've had practices running these programs, we now, when we do have power, know how to do it on a districtwide, citywide, statewide, national, and international level.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Thank you

JORDAN: so much for taking the time out to talk to us.

JAMAL JOSEPH: Thank you.

PRINCE SHAKUR: we have three minutes left.

JAMAL JOSEPH: I want to end with a poem.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Yeah.

JAMAL JOSEPH: The time has come for rifts and revelations [01:08:00] for way out trips to inner space. Now, if truth is one, if truth is really one, then it must be our perspectives that are fragmented. The journeys we all make in search of unblemished realness reveals that much of the rest is a lie.

And if love is to transform and to be transformed, then creativity must be the child of the most perfect union. We may not have all of the answers, but at least let's come together and try to understand the questions through truth filled endeavors that build large creative fires and large, bold actions.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Thank

JAMAL JOSEPH: Thank you

JORDAN: so much.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Yeah,

JORDAN: I had it.

PRINCE SHAKUR: We are, I was hoping to ask you to read and I took that out, so that's great. Thank you.