JAMAL JOSEPH

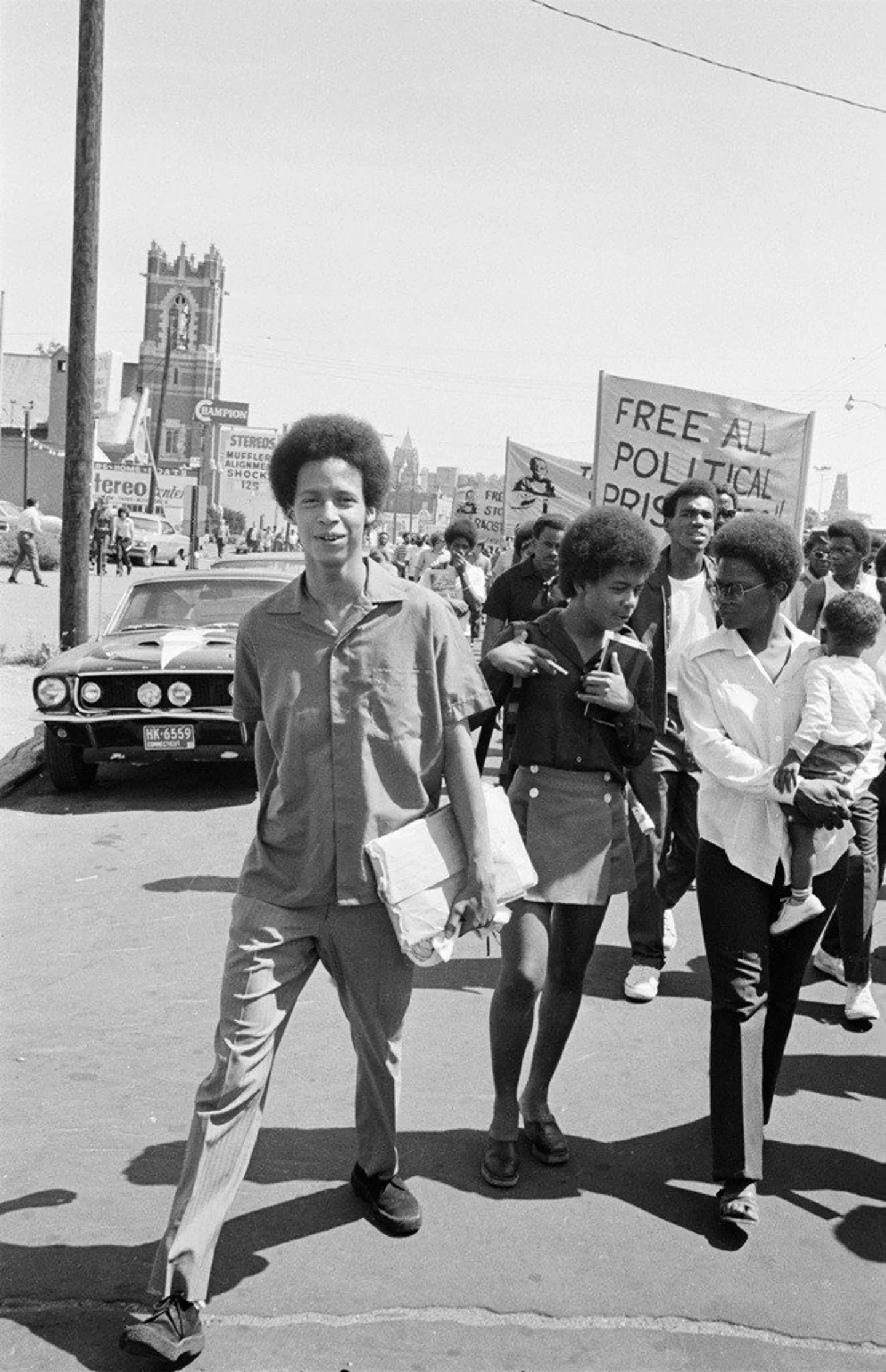

Jamal Joseph is a writer, educator, filmmaker, and former political prisoner whose life reflects both the militancy and the creative resilience of the Black liberation struggle. He joined the Black Panther Party at age 15 and later became a member of the Black Liberation Army, engaging in armed resistance against systemic racism and state violence. Arrested in the early 1980s and imprisoned at Leavenworth, he earned his BA summa cum laude from the University of Kansas while incarcerated, transforming his time behind bars into a period of intense study in literature, political theory, and the arts.

read his interview

JAMAL JOSEPH: The time has come for rifts and revelations. For way out trips to inner space. Now truth is one. If truth is really one, then it must be our perspectives that are fragmented. The journeys we all make in search of unblemished realness reveals that much of the rest is a lie. And if love is to transform and to be transformed, then creativity must be the child of a most perfect union. We may not have all of the answers, but at least let's come together and try to understand the questions through truth filled endeavors that build large creative fires and large, bold actions. But nevertheless, we come together and with love we be trying.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Jamal Joseph is a revolutionary writer, director, poet, activist and educator who began his journey as a member of the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army. After serving six years in prison as a part of the Panther Panther twenty one. Jamal turned his experiences into the foundation for his creative and educational work. He has been a professor at Columbia University's Graduate Film program and the executive artistic director of Impact Repertory Theatre. Jamal's films have been featured on major platforms like Fox and HBO. He's received numerous honors, including an NAACP Leadership Award and an Oscar nomination for his work on August Rush. His memoir, Panther Baby A Life of Rebellion and Reinvention, chronicles his incredible journey and was released in twenty eleven. Welcome to another episode in season two of The Dugout Happy Black History Month. This, I will say, is definitely one of my favorite episodes of the podcast, and it's an interview with Jamal Joseph

JORDAN MAYS: Time and our life and our journey is so precious. And it's conversations like these, not only because they're intergenerational, but because of how much experience and knowledge is being conveyed. Um, and y'all can only get what's conveyed through words. Um, but as we know, there's so much more to that and effective communication. And I think it's a dope moment. I'm excited for y'all to hear from Jamal Joseph. Think about how I think it's one of those folks.

Like, I also wanted to ask them about Sostre but didn't get to. But it's kind of like one of those figures, kind of like how you said in our surgery episode. Um, well, it's an older black man who hasn't failed me. In the revolution, in the struggle. And it's like, I want to hold you tight and have have this moment. And I feel like I spent the most of it so in awe and being like, there's so much you can go through and still survive to be a militant, humanist political figure and being. And I love it to get recognized time and time again.

PRINCE: I was very moved by the whole conversation, and we'll share some afterthoughts. Um, but for me, it comes at the end of a really fucking intense year. Like, what the hell? I just really admire Jamal and especially his writing. Um, because when I was working on my memoir, his book was one of the central texts that kind of let me know, No. Okay. Like, here is a version of what it's like to write about being a young, politicized black body in this country. And I think it gave me a lot of permission. But without further ado, we'll get into the interview. Thank you for being on the dugout. I definitely have thought about, like, our conversation during my New York book launch and then like conversations we had after. And one of our intentions, I guess, in the next year for the podcast is to really dig in and, I don't know, talk to more folks, try to talk to people that have different kind of histories in the movement. Um, and so I definitely wanted to sit down and talk with you.

PRINCE: First question that we like to ask folks is, um, could you just kind of talk about your childhood, what young Jamal was like? I'm of Afro-Cuban descent, was conceived in Cuba. Uh, and mom came to New York, uh, to give birth. Um. Uh.

JAMAL: Here's how revolutionary genes are in the family. My my son Jed often talks about that. Uh, she was in graduate school. Uh, my dad was in the movement, and, uh, she came home on semester break. They had broken up, and she said, uh, mommy, my grandmother, uh, I don't know what to do about this baby. I'm pregnant, you know, and I may need to have an abortion. Uh, the father and I, um, you know, seems like we're having hard times. He's seeing another woman, and I'm not quite sure what to do. My grandmother said, uh, tell me about the father. They said, well, he's a medical student and, um, an organizer. He hangs around with, uh, these guys, Fidel Castro and Raul Castro. Grandmother said two things.

Uh, number one, you're keeping a baby. Number two, I'm sending you to New York and to live with your auntie to have the baby while we figure this out. That led to me being raised. My my mom had been, uh, a debutante in Cuba and, uh, spoke fluent Spanish and French. But in New York in nineteen fifty three, she was a brown skinned woman who couldn't speak English. So she put me in, uh, what was going to be the temporary care of, uh, people who became my adopted grandparents? They, uh, had older siblings and parents who had been slaves. Um, so I had firsthand stories of slavery, Jim Crow, lynching. Um, they came to New York. Grandpa did a number of things. He was a boxer, a cab driver, a numbers runner.

Uh, but they were garveyites. And so I was raised with this kind of triple consciousness, this Afro Caribbean, Afro-Cuban, uh, but also New York City between Harlem and the in the Bronx by, uh, by people from the South, um, who had this profound sense of race and identity and struggle. Um, they raised me. My mom passed away. Uh, unfortunately, um, when I was young, I was ten years old. And, um, I got a wonderful world view from my grandparents, especially from from grandpa, who had a formal education that was probably about the seventh or eighth grade, but was a lay professor in black history. I first heard the names of Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, Marcus Garvey from this man whose back was bent from a life of labor, um, in his seventies, with a full white head of hair that were telling me these stories and teaching me this history. He was also very colorful, so it's not like we were sitting down and it was this real kind of, uh, academic presentation.

It would be more like, uh, I'd be doing my homework sitting with him and a Tarzan movie would be, uh, playing on TV, and he'd let the movie go on for about ten minutes or so, and then he would comment. So this was kind of my first, uh, lessons in thinking critically about race, but also media studies, because here's this commentary. What the fuck is that? Uh, tell me, how in the hell this cracker, uh, this cracker, baby, fall out a damn airplane, swing across the vine. He speak. Margaret. Lion, monkey, tiger, every damn thing. And the Africans look like they're crazy. Change the damn channel.

Yeah. So it will be infused with a lot of, like, his personality, his street savvy, but very clear that we were Africans. This is at a time when you'd get teased in school. Africans would be teased the way we were portrayed, you know, in those Tarzan movies and the other movies, you know, three quarters of the actors weren't even black. They were white men in body paint. So he kind of like, disabused this sense that, you know, the movies were correct or that the media was correct and that, you know, uh, the that the government should not be trusted, that we should understand that we were an oppressed people. Um, and again, in a very profoundly funny and colorful way.

When he passed away, I was about thirteen years old and was a good student, but a little bit of a drift, you know, um, and I was one of these kids that was doing really well in school, but then hanging out, you know, with the gang members and, you know, the street bloods, you know, after school, trying to find that Panther manhood still was going to church, still was involved in community centers, was a member of the NAACP Youth Council. Um, and when Doctor King was killed, um, it it it it made me angry. I can't say radicalized me right away because I was angry without politics.

Um, the way a lot of young people are, the way a lot of people are, you know, there's something in you that gets mad about the stuff that's going on. So I got real mad about it. Got caught up on the fringes of of the rebellion that happened in Harlem, got rescued by a group of black militant men from cops who were kind of chasing me down for no reason, and then decided that I wanted to be a black militant and again, not fully understanding what that word meant.

I just knew that there were people like Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, uh, saying Black Power. Um H rap Brown was, you know, you know, particularly, you know, gifted. Like he was like a poet when he spoke, breaking down what racism was. You know, you, you know, rap Brown would say you've been brainwashed. Yeah. You wear black to funerals, white to weddings. Angel food cake is white cake. Devil's food cake is black cake. You know, even at Christmas time, you know? Tell me, how in the hell, uh, fat redneck honky can slide down a black chimney and still come out white? You.

PRINCE: That's what my mom always said growing up. That's what my mom always said, right?

JAMAL: What's going on with that? So there was a lot of identity and a lot of anger. And then I saw the Panthers soon after that, literally on television, storming the state capitol in Sacramento, calling for self defense, talking about black folks being armed. And I was like, I wanted because you want to If I'm going to be militant, let me be part of the most militant group on the scene. This is I'm fifteen years old, and they were the Panthers and two other friends. And I went to the Panther office. And as we were taking the train from the Bronx down to Harlem, I wasn't quite sure what I was getting into, especially because my friends were saying stuff like, you know, you know, when you join the Panthers, there's no getting out. It's like the Mafia. And my inner voice is like, no getting out. I got a nine o'clock curfew tonight.

My other friend, you have to prove yourself to be a panther. Um, you gotta kill a white dude. I was like, kill somebody. I sing in the youth choir on Sunday. That's my inner voice. Well, we get to the Panther office, and there's the Black Panther logo. We step inside, there's all the older brother panthers and sisters, you know, rocking their leather jackets some had on army fatigue jackets, dashikis, afros, cornrows, berets and I'm just blown away. Now I say older brothers and sisters because I was fifteen. They were older to me, but the Panthers in that meeting were eighteen, nineteen, twenty one, twenty two years old.

The person running the meeting is expanding the Panther ten point program, um, which is now written, I think, uh, fifty seven, fifty eight years ago. But if you read it, it could have been written last, last year. And it talks about, uh, housing, medical care, community control, uh, education. Police brutality is point number seven. It's way down there. In a way. We want an immediate end to police brutality and the murder of black people. I'm not really hearing what he's saying because my heart is pounding. I want to prove to myself.

I want to prove to my friends. So I jump up and I say, choose me brother or me. I kill a white dude right now. Whole meeting gets quiet. The brother running the meeting calls me up front. We're all sitting in folding wooden chairs, and he's behind his old wooden desk, facing us like a large classroom. And when I come up front, he reaches into the bottom drawer of the desk, and I think he's going to hand me a gun. He hands me a stack of books. Um, Autobiography of Malcolm X, wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon, Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver, and of course, the Red book. Quotations from Chairman Mao. You know, all Panthers had that red book. I said, excuse me, brother, I thought you were going to arm me. And he said, excuse me, young brother, I just did. Um, and then as I'm walking back to my seat, he says, brother, I want to ask you a question. Since you came in here so mad at white people.

He said, if all of these people that are in the community brutalizing people, beating people up, locking people up, shooting people down, if they were all black and all the victims of police brutality were white. He said, these slumlords, buildings that are falling down rats and running up and down the hallway, no heat in the winter. All of the slumlords were black and the people living like that were white. He said, these are fascist pig politicians, congressmen, senators, the Supreme Court, the president of all of them were black and all the oppressed people were white. Would that make things correct?

And I said, no, sir. It seems like it would still be wrong. And for the first time he smiled. He said, that's right, young brother. This here is a class struggle for human rights, not just a race struggle for civil rights. Study those books so you can understand what revolution is about. And one last thing. Um, there was a poster of Che Guevara on the wall, and it's a quote from a speech that che gave at the United Nations. And the quote was, at the risk of sounding ridiculous, let me say that revolutionaries are guided by great feelings of love.

So my head was spinning, my world was turned upside down and was within fifteen minutes of walking to a Panther office. I started to have a context of of struggle and approach to revolution that not only shaped my experiences in the Black Panther Party as a political prisoner, prisoner of war, the Bla. But till this day about that approach to struggle, understanding the real foundation of what we're fighting for and understanding. He utmost that we need to be guided by great feelings of love for the people. Yeah. You mentioned how. The assassination of MLK wasn't like the radicalizing point and how this attachment to the politics and the power analysis.

JORDAN: What points or times or stories can you think of, of when you're moving through this ten point program and like the history and you're feeling it and you're organizing? Do you feel like was like radicalizing you or moments that I feel like I'm constantly radicalized. So like things that are like kind of a theme and when you feel.

JAMAL: Um, yeah. I mean, the power of I think the, the, the radical anger, um, happened when Doctor King was killed. I think the political education. So that context to the radical anger. Right. So that's why you see me separated just a little bit. Happened that first day in the Panther Party. Everything was kind of built on that idea of service to the people. Political education was. And political education classes happened several times a week. And then as the. So you would go to, uh, and you were required, uh, to go to at least two political education classes a week and to do community service. By the time the repression, the, the started to increase on the Black Panther Party, you were required to go to political education classes and meetings every day.

And a lot of Panthers left home and lived in Panther, what we call Panther pads or Panther communes. Now, P could look like working through the autobiography of Malcolm X, certainly with PE classes that were about the Red book. But there'd be days where political education classes would be the New York Times or the Daily News, so that you could read something that they had written and learn how to analyze it, or, as we called it, break it down and speak to that. Yeah. So that you weren't just in, uh, you know, what we call these days? Just an echo chamber of just hearing stuff.

And this, this is what taught young Panthers how to think critically. So that when you went in to the communities that whether you were on a street corner talking to brothers and sisters on the corner, or if you're organizing on a college campus and you got into a debate, uh, you know, with an economics professor that you had some context that you could, uh, that you could speak from. And then as I was with older Panther leaders, you know, uh, shadowing them, it would be amazing to see that it would be amazing to see people like Drupal, Benoit or Michael situated to Afeni Shakur, who became my big sister right away because she tried to send me home and tell me not to come back, you know?

I was too young. I love that moment in your book. Yeah, yeah. It would be amazing to be with them during the course of the day and see them being able to talk to hustlers on the street corner, grandmothers who were struggling to keep food on the table for their families, for their children and for their grandchildren, and a political science professor on the campus of City College or NYU and Columbia, and and and be able to talk to all of them and be able to code switch. You know, it reminded me of that moment that, uh, Alex Haley describes being with Malcolm X, that he was on the street corner.

Malcolm was speaking slang and organizing the folks on the street corner in terms that they could understand. But to see him on a college campus and, you know, be able to talk about the issues. Uh, as someone like someone who had a doctorate in political science, uh, to me, I learned that's one of the keys of organizing is being able to kind of communicate. And so that the, the political education classes dealt with all of that. And and it's what made, I think the Black Panther Party both a threat and effective, is that we did have leadership. We did have, you know, national leadership, state leadership, local leadership. But when you are out in the community organizing Panther Papers, everyone could kind of speak to the issues. And, you know, as we say, and break it down and riff and rap and talk to folks.

PRINCE: Thank you for that, because I think one of the questions we kind of had or were curious about was, yeah, how exactly the party led education or what that looked like, or the kind of different things that you would dig into. So I feel like that's super helpful. Um, another question I kind of had was, um, could you talk about, like, the process of you getting deeper into organizing with the party?

Because I know that from the previous interviews you've done, you said at about the six month mark of being in the party was when the Panther twenty one kind of case started, I believe. And in that time, I think you noted that you were leading the kind of like a lot of the organizing around high school students. So could you talk about that period of time leading up to kind of when Panther twenty one happened? And, yeah, how you were kind of taking in these lessons from these other organizers in what in the stuff that you were doing,

JAMAL: the other. So the other key part of one's political education was going to work right away, being put to work right away. Um, again, from a quote in, in the Red book that was one of the, you know, one of the things, one of the principles of, of the party was that all theory is based on practice. So you couldn't just show up to political education class and just be really articulate and be good on the issues. You couldn't just be a theoretician. It would be, you know, where were you? I didn't see you at the breakfast program. I didn't see you when we were, you know, uh, across the street and was still across the street helping lead the rent strike, not only organizing the tenants, but fixing the broken windows and painting and covering up the holes in the ceiling so the rats can't just run over the building.

One of the best compliments that you could get in the Panthers is that you were a good worker. It meant that you were doing the breakfast program at the welfare center, selling newspapers, being the person picking up the clothes from those dry cleaners that were donating to the free clothing program. All of that took work. And that was the best compliment that that you that not you were the kind of, you know, uh, most articulate, Uh, not that you would a badass that when the police did come, got in their face. But the best compliment is that you were a worker working in the community.

So most of what I know about that kind of organizing and about leadership that that, uh, evolved and came with me throughout the life was for was around those organizing principles. Right. Meeting the people at the point. It's what we call having a face to face relationship with the people. Um, and that meant the people knew who you were because they saw you in the community, not just in front of the, uh, the Panther office, you know, on a bullhorn when we'd have those community meetings. But you were there when, uh, when someone wasn't getting medical attention and you helped get them to the hospital. And then once they were at the hospital, there were community folks and other people in the Panther Party standing there demanding immediate attention for that person, whether it was a grandfather or grandmother having a heart attack or a kid having a sickle cell anemia crisis, which would become fatal because my oldest son was born with sickle cell anemia.

The fight for sickle cell anemia I first learned about in the Panther Party moments like that, when we were in the emergency room demanding that a child get treated and get pain pain medication. And then the follow up was a national sickle cell testing program, which which, uh, most medical professionals will tell you is what brought, uh, awareness about sickle cell anemia to the country. Right. Yeah. That was one of the most powerful moments in the book that I, I was like, this is mutual aid. This is direct action. This is community organizing and deepening relationships at a local level. And the things that can be Replicated. Absolutely. And that's what happened. This is really an important point, is that people came out to help run those programs. So it wasn't like this is a breakfast program.

Um, but only Panthers could run it. It was community folk that would come out and would volunteer, that would bring in donations, that would donate their time. It's why these programs outlasted the Panther Party. And, you know, as Sister Ericka Huggins, who's a Panther leader and was a political prisoner, said, we shamed the schools and the government into doing these programs. So, you know, a lot of people said inspired by, she said, shamed by the Panthers to say if we could do it with no money, you know, and then we would, you know, but then we would use that to educate the kids, you know, to educate the families, to say, how is it that, you know, we have a government that can spend billions of dollars, uh, putting a man on the moon, but they can't spend whatever it costs for a plate of food those days.

Twenty five cents, fifty cents. You can't figure out how to put a plate of hot, nutritious food. And in front of a child, you know, a black or brown or, you know, child. And then and then those programs were picked up by other, uh, by other organizations. So, you know, you had the Young Lords, you had Iwakuni Harmonious Fist, you know, from Chinatown. So they they they were doing food programs. They were calling for testing, you know, in Chinatown, the issues were tuberculosis folks living closely and getting kind of community folk involved. So and that was the true spirit of organizing. One of the greatest lessons that I learned about organizing was from Afeni Shakur when she said, Jamal, that the goal of the Panthers is not to have every man, woman and child, you know, sister or brother, he, she or they in the black community become Panthers. It is to teach people the possibility of struggle through example.

And if we do our job, we make ourselves obsolete. You won't need a Black Panther Party because the whole community is organized. The whole community is revolutionary. And that goes back to one of the other, uh, organizing points and sayings. Let the bakers bake. Let the teachers teach, let the builders build, let the healers heal, but let them do it with a revolutionary consciousness. Mhm. Yeah. Every cook can govern. Uh, but Prince, to go back to your point, because I was around so much uh, and you know, you know first became the kid that didn't go away and a little bit like the mascot.

But then uh, then brothers and sisters, you know, took me with them so that I could learn. So I got promoted and elevated. Uh, but that put me in the crosshairs of the district attorney Frank Hogan. When when, um. Uh, when he was organizing the Panther twenty one case. You know, Panther offices were being raided, uh, blown up. Panthers were being arrested. None quite as horrific as what happened to Fred Hampton in nineteen sixty nine. But Frank Hogan said, well, I'm going to deal with my kind of Panther problem situation a little bit differently. I'm going to use the power of the district attorney's office. And if I arrest all of the leadership, you know, if I cut off the head, the body will die.

So everyone who was an officer kind of got targeted in that Panther twenty one case. So I was an officer, I was fifteen, but I was still an officer. And that kind of, you know, fit into that profile, which is why I was arrested, uh, on that that fateful morning in nineteen sixty nine. April second, nineteen sixty nine. It increased across the country. There were bombings. There was, of course, in December of nineteen sixty nine, the murder of Fred Hampton. And then a few days after that, there was the raid on the LA office, which was, um, the first mission of Swat special Weapons and Tactics was against the Black Panther Party. That was a Swat team.

JORDAN: Wow. Yeah. Wow. Yeah. It's just that just brings me back, like so many of the some of the biggest creations for domestic military forces from the state come from and are directly, like, most of the time, a rebuttal to the revolutionary forces of folks, whether it be like even the invention of the FBI, because world leaders were being assassinated in Italy and attempts in America, um, and even just having that sort of political fervor was enough to get the machinery gunning for you.

And I mean, they still still do. And try us. What did you do? Do you remember from, like, the legal support and what that experience was like and how that's maybe impacted or things that you've seen legal support change or how that organizing has evolved?

JAMAL: Yeah. It was it was surprising to me the kind of support that came about. I just want to make one point about what you just said. You know, when, when when J. Edgar Hoover, uh, testified against, uh, or testified in Congress, uh, about the Black Panther Party. He said the Black Panther Party was the greatest threat to the internal security of America. And he was getting congressional approval, an approval That if this is the greatest threat, then you have to give me permission to handle this threat. And it's going to be a program that I'm not going to speak about in this, in this congressional hearing.

But those of you who are on these special committees are going to fund and allow me to do this thing called Cointelpro, the counterintelligence program. And the thing to understand about the Counterintelligence program is it wasn't just good go to good old fashioned police work. Let me put the Panthers under surveillance and go after you know them if they're doing something wrong. It was counterintelligence. It was to destabilize. It was lies. It was phone calls. It was letters. It was agent provocateurs. It was undercover cops and FBI agents to destabilize the Panther Party. Um, which leads to the Panther twenty one case. But here's the important point to remember in all of this J. Edgar Hoover hated the breakfast program more than he hated the self-defense program, more than he hated in those cities that were legal with Panthers, were patrolling the police with legally possessed rifles and shotguns and law books because he understood the the power of that kind of organizing. He understood radical history in a way, uh, you know it in some ways better than we do. Let me give the Cuban Revolution for an example.

When, uh, when, uh, when the when the revolutionaries, uh, the fight, the freedom fighters who would be in the mountains when Batista's troops would move in and they had to abandon the base they found. What did they find at the base? Some weapons. Most of the weapons were gone. They took it with them, but they found schools and clinics Wherever they went, they found schools and clinics. Outdoor schools, clinics. Because when the rebels would secure, the revolutionaries would secure something. They understood that they were there fighting for the people. And the best way to organize the people is to show them that we, this revolution, is going to do things for you that the government is not doing for you. And so and that's why one of the first mandates of the Cuban Revolution, when you look at it, was to end morphine in, uh, in the literacy and infant mortality. Cuba still leads the world. They have a higher infant survival rate than we do here in the United States, especially in communities of color, so that when we when we when we would read what was happening and get a chance to meet folks who were from Cuba or travel to Cuba, go to these different places.

These were the lessons. Not just the theories, not just the quotations from Chairman Mao, from Che Guevara, or from Amilcar Cabral, you know, from all of these great revolutionaries. What were they doing on the ground? That's what we had to do in the community. In fact, when you left the Panther office, you would say to people, I'm going into the field to organize. And when we would go downtown, we would say. And we would say, well, what are you going to be in the colony or the mother country? We're saying going to the mother country. Maybe you were going to go to, you know, forty second Street and try to sell some papers and organize some folks. So those lessons. Right.

And and what I'm hoping people take away from this conversation is that it's got to be so people centric. If you want to study these struggles, you have to see what what the people did in those ports, in those poor towns, in the mountains and in the jungle to organize folks. And that is around their needs. And then you politically educate folks, and that's why you build what they call populist support. That's why part of why no Panthers were killed in the LA shootout was the brilliance of Geronimo Pratt, who built up the defenses, the defense system and sandbags and trained the Panthers. Geronimo Pratt was deputy minister of defense. He was a Vietnam veteran, but also those community programs that when the police were were doing that shootout, which lasted for about thirteen hours the whole time, people were on the streets behind barricades watching, saying, don't you murder those Panthers? Don't you murder those those, those, those comrades, don't you murder?

And the grandmothers were out there. Don't you murder those children. Those are my babies. I saw them grow up. Grow up. Or if they didn't see them grow up, they feed my my grandbabies.

Right? So I want to, you know, kind of come back to that now for the Panther twenty one case. The core of that was, uh, were people part of an elite police unit called the boss unit that infiltrated the Panthers, that became members and leaders. Right. And they were the ones that that that would bluster and be the most radical and said, you know, when when a tenant would come in and said, we need help in this building, when a group of tenants and, you know, a fainting and other people who attended organizing would say it's going to be a rent strike, and we're going to have people have lawyers to volunteer to set up escrow accounts, and we're going to make the repairs.

We will be there to stop the eviction, but we're going to, you know, be able to show where the money went with the landlord wasn't doing. And you get someone like a yeywa, uh, who is an undercover cop that would say, you know, listen, we're revolutionaries. Let's find out where the landlord lives and drag him from his house and put him on trial. A public tribunal in Harlem and lynched him and stuffed a rat in his mouth. And of course, we would be like, yeah, you know, the younger the younger brothers would be like, yeah, let's do that, you know? And someone like Afeni Shakur would say, and then what happens to the people? And then what happens to that building? We're inviting repression.

We're inviting that. So those, you know, but that's what the agent provocateurs would do. And that's what the counterintelligence program is about.

They would do letters. They would have people in the meeting not just to observe, but to urge people to take radical action that could be the cause for arrest or could be the cause for a raid or could be a cause, uh, you know, for for someone to get to for someone to be assassinated. In those days, um, you know, they would have to send someone in to infiltrate. They would, uh, in some cases, get the, you know, if they were going to make a court case, have to get wiretap orders from a judge so that they could place these listening devices. Now, all they have to do is just turn your phone on in a meeting.

And now we get into these heavy debates. Prince, you and I talked about this at your at your book launch. You know, we will get you get into thinking. Thinking that you're in a heavy ideological debate with this, you know, this this comrade that lives in Seattle, Washington or Miami, and you haven't seen them, don't know them. How do we know that quote unquote comrade is not sitting at some CIA, uh, terminal in Langley, Virginia? Yeah. Or FBI headquarters in Washington, DC. So when when we talk about the takeaways,

I want to I like to talk about the community program and that aspect. But the, the, the the destructive nature of the counterintelligence program. And will it be five or ten years from now, will we know the name of the new program? And will we see how many of you know of our family, our comrade family, uh, went to prison, was killed or, you know, got got so depressed that they had to kind of leave the struggle. So their lives were ruined in other ways. You know, there's other ways to ruin lives than just assassination or imprisonment. You know, you can cause someone to have a dissolution of their family, their mental health, their physical health, all of these things. So it's all stuff to kind of pay attention to when we try to look at the lessons of that period. Jad and I are working. My son Jad are working on a documentary about the Panther, twenty one, and, uh, Gerald Lefcourt, who was lead counsel, talked about the challenges of that case that we and he used it in contrast of the, uh, the Chicago seven case, where they were antiwar leaders.

They were well funded. They were well known in the Panther twenty one. We weren't known. We were known in the community, but not nationally known. Bail set at one hundred thousand dollars. No money, no support. And Gerry went to a couple of students who were anti-war, uh, Organizes Columbia students who he had represented for free, saying I need help organizing. And they built a Panther twenty one Defense Committee. That was amazing. Students were involved, and the other thing that they did was that it was a broad based coalition. So you had originally predominantly white students, but then City College students and then community folk, uh, and other folk. And they were pointing out that, um, that here are men and women from the community who certainly can't afford one hundred thousand dollars bail, because who were the Panthers? Who were the Panther 21?

Students, workers welfare mothers, uh, former street people. You know, a couple of people who had been, you know, formerly incarcerated folks, um, Veterans. We had, uh, one person who was a mathematician and had worked at NASA for a little while. Wow. Uh, Curtis Powell, who was a who was a biologist, but no one had one hundred thousand dollars, and, uh, which is about nine hundred thousand dollars in today's money. I first, uh, started to understand the sophistication of what was going on when I had been in prison for about three months, and they brought us all together in court because initially they separated all of us, so we couldn't communicate. So it wasn't like the twenty one was all in one jail. Afeni Shakur and Joan Bird were in the women's house of detention. Um, myself and a and a panther named, um, Alex McKeever. We were on Rikers Island. But even on Rikers Island, we were separated. So when we'd have a court hearing, they'd have to bring us in from all different points, and then we'd have that court hearing, and then afterwards we'd all be in a large cell conferring with our lawyers.

So I just knew that we were having a bail hearing. And beside our lawyers, they were lawyers from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. I was like, what is the NAACP doing here? And the NAACP Legal Defense Fund was there because they believed that we were being prosecuted and persecuted because of our political beliefs. And even though the NAACP obviously had different beliefs, the mission of the Defense Fund was to look at arrests that were racially motivated because of race or because of someone's beliefs.

This blew my mind, but it made me understand the sophistication of real organization. Bring people around the issues. Yeah. We in turn may bale an issue for everybody that was being held. So there was a rebellion, if any was bailed out. I was bailed out. And the Panther leader, Dhoruba bin Wahad had been bailed out. The remaining Panthers we had by this time won a motion to all be housed in one prison, which was the Queens House of detention, or called Branch Queens in Long Island City. And the Panthers led a rebellion taking over that prison. It wasn't the typical we want better food or we want more time, more recreation time. Number one, demand was bail hearings, and judges were dispatched to that prison to have hearings in the prison visiting room. And about thirty men were released that day. And it happened similarly. Wow. So this is how you can take an issue and organize around it.

We made this an issue in the courtroom. We made the issue of jury selection, which was one of the points in the ten point program. We went to a trial by a jury of our peer group. And when we say we in the ten point program, it wasn't that we the Panthers. It was like we were recognizing that historically, people were arrested and tried and convicted by all white juries. So the point, I believe it was point number eight, we went to trial by jury of our peer group, and we defined that as someone from your same socio economic and racial background. We made this a big fighting point in the Panther twenty one trial. And we talked about all white juries. We talked about that when we were doing the voir dire process, where the lawyers get to examine the jury, we would say, do you know that there was an organization called the Ku Klux Klan? Do you know about people who legally lynched, and the jury selection process, which usually just takes a day or two. Um, you know, sometimes just an hour or two in a criminal case.

Our jury selection process was was a month. And and it's because we wanted to make everything a fight. We were convinced that we would be railroaded, that we would be legally lynched. But why were we here? And this is why Afeni Shakur said, I want to represent myself, to be able to speak directly to the court and to the jury, and such a way to bore us. We wanted to fight to show that our trial was a legal lynching, but it was representative of what was happening all all across America. The amazing thing about this is that we seated the most diverse jury that Manhattan had ever seen. Now you go to to a jury in Manhattan, you, you know, you're going to get a diverse jury. But then juries were mainly white men. And when we talked about these issues of self-defense. Yes. You know, the police, when they raided our apartments, found weapons in every apartment. Do you understand why? Because of police terror. Because of the history of the Ku Klux Klan. Slave patrols. Why? Black people feel that they have to defend themselves and protect themselves. So we made that a repeated point.

We talked about community programs. What we didn't realize in the Panther twenty one is that because we had selected the kind of jury that we selected, they were actually listening to what was going on. So to everyone's surprise, at the end of the trial, which which lasted thirteen months and the whole procedure was from the time the path of twenty one was arrested until the until the verdict was two years that the jury found On the Panther twenty one. Not guilty on every count.

Yeah, that that was like fantastic. And and you say you think that has a lot to do with like the putting up a constant resistance during every single part of it. Whether or not did you have did you think that you were going to win or that there was that much of a chance at winning at all? It was just fight because there's nothing else to do. For us, the victory is that that is that we had this Defense committee that we knew had become a model for resistance, because when you looked out in the courtroom, there was those white students. There was other folks from the you know, from, you know, folks from the antiwar movement, from from from the, uh, from the women's movement, uh, for what was called in those days, the Gay Liberation Front workers. Um, Um, uh, you know, uh, folks from all communities black, brown, red, yellow, you know, the Panthers, uh, greeting was all power to the people.

And, you know, and, you know, when you were doing a political education, Castle rally, people would say, right on. And then you would you would break it down. That means black power for black people, white power for white people, red power for red people, Brown power for brown people, yellow power for yellow people. Uh, gay power, the gay folks, uh, workers, power workers. And you understand that that's the united front that you were building. So when you look at the Panther Defense Committee, that's who you were seeing when we spoke. When Afeni and I got out on bail and other people, we we would, you know, we'd be at rallies or we'd be at, uh, there was an organization called the Committee of Returned Volunteers.

These were Peace Corps volunteers who had come back, and that committee became Panther supporters. There were Quaker organizations that supported the Panthers. And it's not they agreed with with everything. Uh, most people saw the ten point program as something that, that, that, that they could agree on. But we were a we were we were a revolutionary Marxist organization. We were calling for class struggle, class warfare, the abolishment of the capitalist state for people's government. But there were people who said, I don't know if I'm behind all that, but I can get behind the idea that everyone deserves medical treatment and that police should not be, you know, uh, you know, the armed assassins for the state. We were able to connect antiwar kids with the idea of if you believe that there's a war of aggression happening Vietnam, then you have to see the war of aggression happening in black communities.

So it radicalized. But then we were able to come back to our communities, sitting with folks from these other, uh, movements, from these other organizations and organize around that. You know, when you see the antiwar kids don't throw rocks at him or tell them, get off one hundred and twenty fifth Street because they're they're fighting the same battles that we're fighting against state terrorists, state murder, you know. So you bring that consciousness. You bring what's what, what what you're learning in the women's movement or the, you know, uh, you know, or the GLF, the Gay Liberation Front to talk about. We got to talk about what's happening in the black community and that some of our, you know, some of our great leaders, you know, great civil rights leaders, great revolutionary leaders who who were and who are queer. So let's stop that. So you're able to kind of talk about that.

There's articles that you can go back in the archives and see that Panthers took a position of that not only in meetings, but in the Black Panther newspaper to talk about that. So the idea of building a united front when the Panthers in, in the days before the organization was really kind of forced to shut down all of the offices so many Panthers had been killed, were underground, were in prison. Two things I want to point out. It was the women of the Black Panther Party that helped helped the Panthers last as long as it did. There were times that you could go in to Panther offices and that it was entirely staffed by women. But because these sisters were such great leaders, so strong, it probably didn't hit you in that way. But that's what was happening. The other thing is that we stopped opening Panther offices, and we were opening what was called United Fronts. A United Front Against Fascism offices.

This is why some people think they were white panthers. You know that they were Asian panthers because they see people coming in and out of those offices. Because because we realize that's the most important organizing that we can be doing now. Uh, we could be doing then as it is now, is build a united front against fascism. And really, really importantly, what we learned. Malcolm X talked about it in his speeches. Doctor King talked about it. The Panthers talked about it. Instead of fighting about the ten things that we don't agree on, let's come together on the three things that we can agree on and organize around that.

PRINCE:

JORDAN:

JAMAL:

PRINCE:

JORDAN:

JAMAL:

PRINCE:

JORDAN:

JAMAL:

PRINCE:

JORDAN:

JAMAL:

PRINCE:

JORDAN:

JAMAL:

PRINCE:

JORDAN:

JAMAL:

PRINCE:

JORDAN: