EDUCATION MODULE

INTRO TO BLACK ANARCHISM

WHAT IS BLACK ANARCHISM?

THE DUGOUT recommends… THE BLACK POWER MIXTAPE

LEARN MORE ON THE PODCAST

🧠 Common Terms in Black Anarchism

✊🏾 Anarchism

A political belief that rejects all forms of domination—like the state, capitalism, police, prisons, and patriarchy—and calls for collective, voluntary ways of organizing society without hierarchy. Black anarchism centers the lived realities of Black people surviving these systems every day.

📢 The State

The government, its institutions (police, courts, military, schools), and its monopoly on violence. Black anarchists see the state not as a neutral structure, but as a tool of white supremacy, colonialism, and capitalist control.

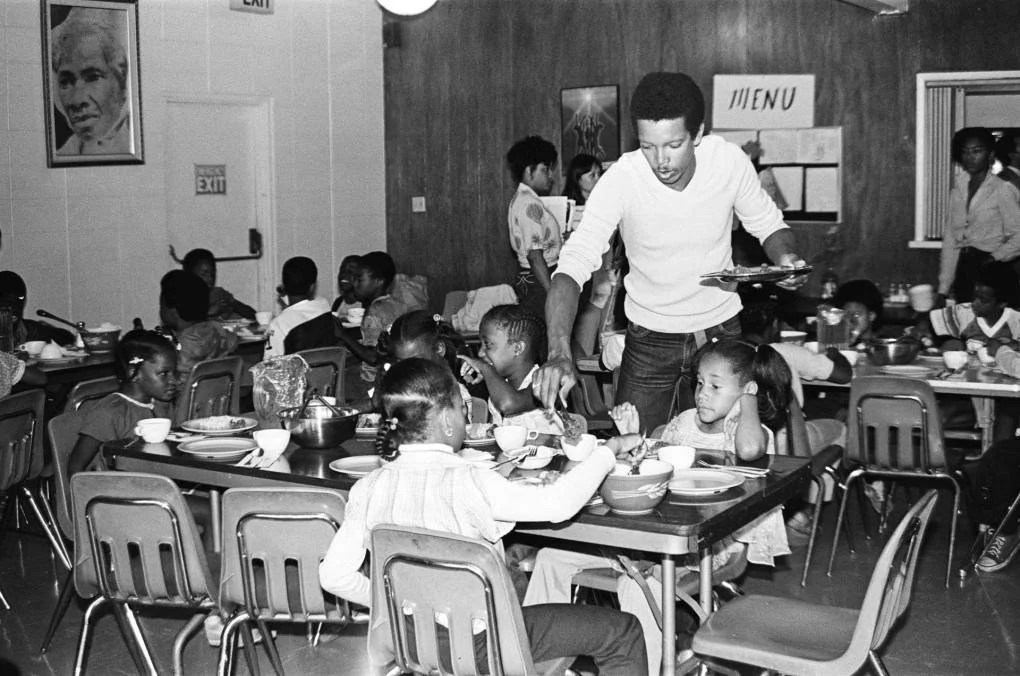

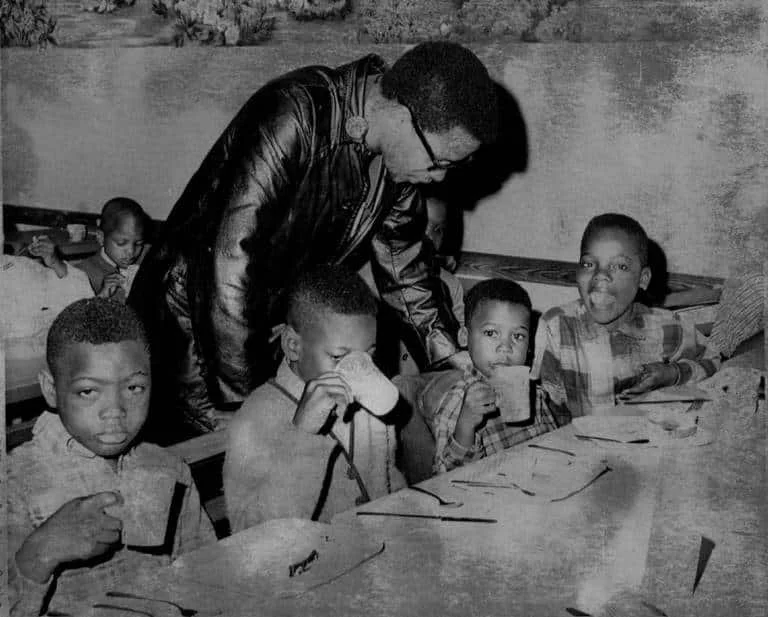

🖤 Mutual Aid

People supporting each other based on need, not profit or charity. Mutual aid is a survival strategy and revolutionary practice—whether it’s sharing food, housing, skills, or protection. It’s about building relationships, not saviorism.

🚫 Hierarchy

A system where some people have more power, control, or value than others. Black anarchists reject hierarchies of race, gender, class, ability, age, and more—including in our movements.

🔥 Direct Action

Taking action collectively to meet our needs or confront injustice—without waiting for permission from the state, nonprofits, or institutions. Examples include strikes, blockades, occupations, and community defense.

🏚 Prison Abolition

The belief that prisons, police, and punishment systems cannot be reformed—they must be dismantled. Instead, we imagine and build new ways to deal with harm that center healing, accountability, and care.

🧬 Colonialism

The violent control of land, people, and resources—past and present—by empires or nation-states. Black anarchists connect today’s systems (borders, policing, capitalism) to legacies of slavery and colonial domination.

🌱 Liberation

Freedom from all systems of oppression—not just legal rights, but the transformation of how we relate to each other, the land, and ourselves. It’s not given—it’s taken, built, and lived.

Timeline of Black Anarchist Thought & Resistance

Late 1800s – Lucy Parsons (c. 1853–1942)

After the 1886 Haymarket affair, Lucy Parsons became one of the most forceful anarchist voices in the U.S., speaking out for labor rights, racial justice, and gender equality. She co-founded the Industrial Workers of the World and spent decades editing radical newspapers like The Alarm and Freedom.

Known as "more dangerous than a thousand rioters" by Chicago police, Parsons built a militant, multiracial movement rooted in direct action and collective power .

1970s–1980s – Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin (b. 1947)

Former Black Panther and anti-war activist, Ervin embraced anarchism in prison in the late 1970s. His book Anarchism and the Black Revolution (1979) interweaves Black Power, anti-racism, and anti-authoritarian politics.

Upon release, he continued grassroots organizing—against white supremacist violence, police murders, and systemic racism—with strong anarchist influences.

1970s–1986 – Kuwasi Balagoon (1946–1986)

A Black Panther and BLA member who embraced “New Afrikan Anarchism” while incarcerated, Balagoon escaped prison twice and engaged in armed liberation efforts.

In his prison writings, he insisted on collective survival strategies: rent strikes, occupied buildings, anarchist clothing co-ops, communal gardens—while refusing to plead in court, declaring himself a prisoner of war The Anarchist Library.

Openly bisexual, he also called out erasure within revolutionary circles, becoming a touchstone for queer Black anarchism.

📚 Martin Sostre (1923–2015)

Black Anarchist. Prison Abolitionist. Political Educator.

Martin Sostre was a revolutionary prison organizer, educator, and one of the earliest voices linking Black radicalism with anti-authoritarian thought inside the U.S. carceral system. Born in Harlem, Sostre became politicized during his incarceration in the 1950s and 60s—first through the Nation of Islam, then through Marxism, and ultimately anarchism. While imprisoned, he transformed his cell into a library and study space, teaching fellow inmates about capitalism, racism, and colonialism.

After his release in the 1960s, Sostre opened the Afro-Asian Bookstore in Buffalo, New York—an anti-imperialist, Black liberation space that quickly became a hub for revolutionary learning and surveillance. In 1967, he was framed and imprisoned again for his organizing and political influence. His case sparked national defense campaigns and exposed the role of prisons in silencing radical Black voices.

In prison, Sostre refused to comply with racist, punitive conditions—defying strip searches, solitary confinement, and censorship. His writings called for the total abolition of prisons and the state, rejecting the idea that justice could ever come from carceral institutions. He influenced generations of Black anarchists and abolitionists, including Kuwasi Balagoon and Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin.

MARTIN SOSTRE: A Legacy of Jailhouse Law, Prefigurative Politics and Revolt

LEARn more about martin sostre

frame up! - documentary

“One of the most important lessons I also learned from anarchism is that you need to look for the radical things that we already do and try to encourage them. This is why I think there is so much potential for anarchism in the Black community: so much of what we already do is anarchistic and doesn’t involve the state, the police, or the politicians. We look out for each other, we care for each other’s kids, we go to the store for each other, we find ways to protect our communities. Even churches still do things in a very communal way to some extent. I learned that there are ways to be radical without always passing out literature and telling people, “Here is the picture, if you read this you will automatically follow our organization and join the revolution.” For example, participation is a very important theme for anarchism and it is also very important in the Back community. Consider jazz: it is one of the best illustrations of an existing radical practice because it assumes a participatory connection between the individual and the collective and allows for the expression of who you are, within a collective setting, based on the enjoyment and pleasure of the music itself. Our communities can be the same way. We can bring together all kinds of diverse perspectives to make music, to make revolution.

How can we nurture every act of freedom? Whether it is with people on the job or the folks that hang out on the corner, how can we plan and work together? We need to learn from the different struggles around the world that are not based on vanguards. There are examples in Bolivia. There are the Zapatistas. There are groups in Senegal building social centers. You really have to look at people who are trying to live and not necessarily trying to come up with the most advanced ideas. We need to de-emphasize the abstract and focus what is happening on the ground.

How can we bring all these different strands together? How can we bring in the Rastas? How can we bring in the people on the west coast who are still fighting the government strip-mining of indigenous land? How can we bring together all of these peoples to begin to create a vision of America that is for all of us?

Oppositional thinking and oppositional risks are necessary. I think that is very important right now and one of the reasons why I think anarchism has so much potential to help us move forward. It is not asking of us to dogmatically adhere to the founders of the tradition, but to be open to whatever increases our democratic participation, our creativity, and our happiness.”

WHO IS ASHANTI ALSTON?

Ashanti Omowali Alston (born 1954) is a prominent American Black anarchist, activist, writer, and former member of the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army The Institute for Anarchist Studies+15Wikipedia+15Internet in a Box+15. Arrested in 1974 for a BLA-related bank robbery, he spent over a decade in prison, during which he embraced anarchism—shifting away from Marxist-Leninist frameworks he once followed OpenLab+2Wikipedia+2Internet in a Box+2.

Alston’s political journey centers on merging Black liberation and anarchist politics—rejecting hierarchy in both state and revolutionary organizations. He became known for his “anarchist Panther” identity, critical reflections on nationalism, sexism, and institutional power within radical movements Reddit+2Wikipedia+2Reddit+2. Since his release, he has been a vital voice in political education, abolitionist organizing, and queer-inclusive praxis, and serves on the steering committee of the Jericho Movement to free U.S. political prisoners The Institute for Anarchist Studies+9thejerichomovement.com+9Wikipedia+9.

Additionally, Alston remains a prolific speaker and elder in radical spaces—delivering talks like “Black Anarchism” (Hunter College, 2003), participating in anarchist bookfairs, and writing essays that highlight the need for anti-racist and culturally diverse approaches within the anarchist movement itsgoingdown.org+7The Anarchist Library+7OpenLab+7.

In short, Alston stands at the crossroads of Black nationalism, prison abolition, queer liberation, and anarchism—offering grounded analysis rooted in lived experience, love, and struggle.