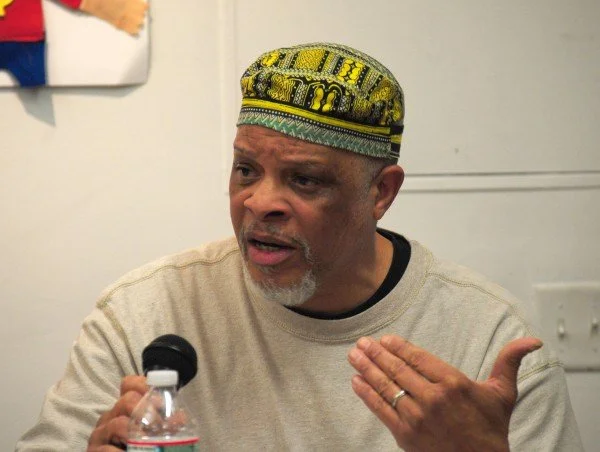

AN INTERVIEW WITH ASHANTI ALSTON | PART 1

JORDAN: [00:00:00] Hello, welcome to the dugout. Thank you so much for coming on Ashanti.

Ashanti Alston: Thank you for having me here and I'm going to admit that I am nervous and all that stuff, so take it easy on the old man. 'cause this is going to be other people listening. Better take it easy with the old man.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Yeah, no, we will. We will.

Absolutely. Um, but yeah, thank you for being here. We're really excited to talk to you. One of the first questions we really like to ask folks that are on is what was a young you like? What was a young

Ashanti Alston: Ashanti like? Younger Ashanti was Michael Austin. Plainfield New Jersey. Born in 1954. The baby of the family, two brothers and two sisters, parents and my grandmother.

Plainfield, a small city in, in New Jersey. Black community was mainly in the West End, and that's where I was born and raised, coming out of a Hebrew Israelite church, born into a Hebrew Israelite church, but at a certain point by five, my father and others left [00:01:00] towards a a Baptist church, but my mother's side of the family stayed Hebrew Israelite.

That becomes important because later on, 50 years later, I'm heading back to the Hebrew Israelite. Direction not to be confused with those who images of Hebrews, Israelites with the outfits and the, the very disrespectful shit they do on the corner corners or whatever city they belong to. Not associated with that.

But anyhow, so coming out of a family, the, definitely a religious family, but not strictly religious. 'cause we was, it was like we was never made to go to church and all that stuff. But definitely played a part in who I am, 1954 by 9, 19 65, 66, 67, you got these rebellions going on by 64, 65. I'm not much of a reader.

I'm a, I'm a kid. Not much of a reader didn't, don't even really remember when Malcolm X got killed in 65. Do remember when Martin Luther King got killed? But even before Martin Luther King, the [00:02:00] 67 rebellions, it was major. And I think the only way to to kind of understand that is families would gather around the television, which I think a generation ago it might have been.

Families and communities would gather around the radio, like to listen to the the Joe Lewis fight or whatever other news thing was on. So there wasn't a lot of channels, but you was definitely focused on the news. You see the civil rights movements, you see the rebellions and stuff. But in 67, Plainfield had a rebellion that followed Newark and Detroit and all the other ones.

Feel like that was my entry into that revolutionary struggle, the black power movement. Stokely, Carmichael H Rap Brown and all that stuff. But significant with playing field and, and I've shared this many times, playing Field's Rebellion was a little different because. There was a gun manufacturing place right outside of playing field, and folks made their way and, and raided the gun manufacturing place and brought back [00:03:00] crates and one rifles, and so they actually ran the police out of the community, out of the, at least the, the black neighborhood in the west end.

I wasn't close enough to see the direct fighting, but sometimes you, you could hear the gunshots and the stuff like that. But there was one particular day, I just remember it so clear that there was a black car that kind of pulled up right in front of the house or pretty much close to the house black car that on the top of it, it had written large black power and they opened up the trunk and they was giving out stuff, you know, to the people and all this other stuff.

And that so impressed me. I had some kind of understanding what this black power thing was, but to see what they were doing. Just took me. But what happened after that? Maybe in a matter of a day or two, maybe longer than a day or two, you would see the National Guard tanks coming in and you could see that they were retaking.

The neighborhood [00:04:00] or, or that area that was considered the black area and what they did on the intersection, man, any black car that was going by, they're stopping the car, they making the out, and they're harassing them sometimes beating them when we would be sitting out on the stoops and everything, watching it.

And there was a time where my oldest brother, Joe, and his crew seemed like they were moving towards either towards the intersection, but they were taking off somewhere and being younger, I, you know, it's like I wanna go. But I can I just get that look from my brother? Like, no, you ain't going. And so wherever they went, whatever they did, I don't know.

But me and my friends took off in another place and just got rocks and we're just. Tossing rocks and all that kind of stuff there. And so it made me feel like we're in it. And that's why I say I don't feel like we are in different, when you see them, kids in Palestine tossing rocks at the tanks. [00:05:00] We are in this fight.

We are teenagers, yes, but we understand what's going on. I feel like that was my entry because after that I'm reading everything I can. Struggling with Malcolm's autobiography. There's a community center not too far away, and there's meetings going on there and, and a lot of the meetings are very political.

You hear people speaking to the impact of the Black power ideology.

PRINCE SHAKUR: You were struggling. Why were you struggling with Malcolm X's autobiography?

Ashanti Alston: Because it's a thick book. I was not a reader. It's a thick book with small print. I'm like, man, because I didn't even do it in school that well, I mean, when they give you the book report and stuff, I didn't do that well, but I couldn't deal with that thick, small print.

But I'm motivated now. I couldn't read it straight through, but I would read it in bits. But I did complete it, you know, and it was just like, the more I read. The more I was understanding this struggle, the history of [00:06:00] this country, how we needed to fight back. But yeah, but like in school I, I mean, when it came to the English good with writing, good with sentence structure, all this other stuff, but when it came to the book reports not so much.

So that, so I had that struggle that same way with, with Malcolm and, and only because of that it was like, oh my God, this is like too much, the print is too small.

JORDAN: When you described the moment of them coming back with the crates of the M ones, as a kid, as a resident. Like, how did you feel about like the security formations coming up and like seeing your brother fight or like doing, going off to go do God knows what, how does that resonate with you or what was the kind of things going through your head?

Ashanti Alston: Well, one, you know, I, I always look up to my, both of my brothers, like my oldest brother, he's like seven years older. My, my next brother, he's a year older. Always looked up to my brothers. 'cause this was also during that sixties period, you got not only the black power spokespeople like Stokely and them that you [00:07:00] might see, you got Muhammad Ali.

You start to see the beginnings of Bruce Lee, but you would see different figures that was also helping you to develop this new pride. So knowing that my brothers and them, you just know they going to do something and that made me look up to him and also honor. What they were doing and like, I wanna do like that too.

I wanna be that person too, to fight back. And it didn't matter that like even with the tanks, you know, you're seeing the tanks and the soldiers on your, on your inter right, the intersection right up the street. It only made you angrier. Especially because you watching how they're treating the black people in the black cars and the order black passengers, that it made me want to know more in terms of the fight back.

Because what you will see in the news with these rebellions. You would see these gun battles going on different cities. It was something about it. We are standing up to these people, you know, [00:08:00] more of our lives was lost. Then theirs, it really didn't matter. And then when you, when I finished reading Die Nigga Dies H Brown's book, he said that playing field had the only successful rebellion because one, no black people got killed and only this one white cop.

But how we were able to get them guns and actually run the police out, it didn't say much about the repression that was going to follow. Because it was definitely repression that followed and people that they locked up for the death of the cop. It felt good to know that people in your community stood up and fought back, and that just resonated with me.

JORDAN: How do you feel like that repression shaped coming up in Plains Field after that, getting into more sustained organizing as well as like, did you see community support for the folks who were getting arrested for actions taken during the uprising?

Ashanti Alston: There definitely was support and one of it is so funny, not that I seen a lot of it, some that you was able to participate in.

Like when I went to the community center, there was always. [00:09:00] Updates on the folks arrested and developing support, but also later when I was able to, um, do research around it, I'm talking about years later, I got to see that it was not on these little meetings and things we were doing, learning and then support for like this got down to two main people for the death of the cop.

You found out that there was churches involved with support. You found out that a version of the Black Panther party. Shortly in playing field even before me and Jihad, you'll hear me talk about that later. Even before we even formed one, there was actually one that existed for a hot minute. There was that there was the Nation of Islam, I believe.

There was a, a group that, um, more followed the, um, the cultural nationalism of, uh, er Baraka. 'cause er, Baraka's group was right outta Newark. You know, Newark is not that far from playing field. I know what we participated in and in the schools too, [00:10:00] because at some point, two junior high schools in the high school coordinated a march to City Hall to demand black history.

When we went there and demanded it, we won. We won that battle because when the school year started in September. Because all this was in the summer, we had black history and that for me was like, this is the result of us organizing. This is the result of that black power is a result of us making a demand and having some level of a political consequence if we don't get it.

And that stayed with me. Just that experience there, like the organizing part, you know, it was like a no brainer when the, when me and my friends, you know, found out about the Black Panther party. That was like, oh, we wanna know more about them. That was definitely the direction that many of us headed.

PRINCE SHAKUR: You mentioned your friend's father took you and your friend to a bunch of different offices and you were able to kind of see the different vibes of the different [00:11:00] chapters, and then you got into starting your own chapter and in other interviews you've talked a lot about doing a lot of organizing with like younger folks and like otherwise, but yeah, could you kind of paint.

Of time, because I know, um, especially before you got those framed up charges, it seemed like. You were very intensely organizing and learning and I dunno, I guess I'm just interested in like what getting into that zone and and mind space was like for you at the time or what the day-to-day looked like.

Ashanti Alston: I think one of the big things was the constant learning thing.

I am like reading now you talking about somebody that didn't like to read. I'm reading all the time. It's not only the black history, but now we're reading the revolutionary ideologies and the theories and the stuff like that. I guess before we got to the theories. When we started going to the offices, like this is Jihad, he's at Jihad Abdul now, and, uh, who I just seen in Atlanta.

'cause we had a national Jericho retreat. We was [00:12:00] curious and his father was curious and at some point, um, his father took him and his mother to visit the office, I think either in Newark or Jersey City. And then one on the other times they went, they took me. So we would go to the other chapters, Newark, Jersey City, uh, Harlem, the Bronx office.

And it was always a learning experience. They may be having, uh, political education classes, but they're always there talking to you. You got all kind of literature here. You got all kind of newspapers. They, at a certain point, they would even allow us to sell the newspapers, and I think it was when. We expressed an interest in that we wanted to start a chapter that there was a certain point where they gave us permission to do that in playing field, and you're talking about, except for Jihads father and maybe one or two other [00:13:00] adults, his father was able to get us a store.

That storefront became the office of this Black Panther chapter. But you gotta go through phases. So when you first establish an office, it's called the Black Community Information Center. And then after you're doing that for a while, you graduate until you become an an official chapter, black Panther party playing field, you know, that type of thing.

But I'm gonna tell you this, like the more I learned, the more excited I became, and I'm sure like Jihad and others too. The theory, and this is the theory part on the reading list and things that you were supposed to read, was Communist manifesto besides WB Du Bois and maybe Robert Williams and stuff like that, you know, to get grounded in your own history, you're developing this ability to look at your society from a class perspective and is laying this thing down in terms of what capitalism is.

For me, that's like, oh my God, it's, it's a real [00:14:00] intricate monster. And so the more I saw that even that ability to see this thing differently, like that just kept me going. The fight back part was not only was the Panther's real militant and you know the thing about being armed and the concepts of revolution, and then you start to understand the guerrilla warfare stuff.

You start reading the newspapers and you see how. How the newspapers are full of articles with struggles all around the world, as well as within the United States. As well as Canada and the southern part, and you're seeing like, man, we're all in this stuff together against these different capitalist systems, against these different imperialist systems.

And it takes you outta that, not that thing of you're not alone. That was really, uh, fortifying in terms of, I, I feel like my [00:15:00] commitment. Like, oh yeah, we are gonna do this right in the United States too. Like it is, like we're uniting with all these people that we may have never even seen before.

Indigenous person. I, I can remember when the first Spanish speaking family moved into playing field and whatnot like that. But now you are meeting people, you meeting white folks who I was not fond of. Who are part of the anti-war movement, or who are solid supporters of the PLA Black Panther party platform and program.

That was really new stuff. Like I said, I wasn't fond 'cause my nationalism was definitely coming outta that more black nationalist thing. Nation Islam. I was never a member, but white man as the devil made sense to me why we wanna work with him. But here the Panthers is like, you know, you work with your allies who's ever, you know, down to change this country.

You know, you work with and then later the thing with women and and all that other stuff.

PRINCE SHAKUR: What other folks that you were working [00:16:00] around stuck out to you in terms of work ethic? Because it seems like the different ways that you've talked about it, you've talked about like, I would be one of the first people to show up to the office and you tried to be very disciplined in your work.

But yeah, I guess I'm one curious like what other folks ethnic you admired? And then I also know that you said in another interview that. In your, I think you said your junior year you ran for vice president, and you said your speech was heavily influenced by Eldridge Cleaver, so I'm also curious about that speech.

Ashanti Alston: Okay. Okay. On the work ethic and stuff, a lot of that was. Out of Mals Red Book. Mal had a whole thing around how we were supposed to be towards people in the community, how we were supposed to be towards each other. A lot of it was really, really good stuff from how you speak to people. Don't take a single needle, a piece of thread from the masses.

It was like so many things in like what we're studying from now. That was encouraging us to be [00:17:00] very mindful of how we are with each other in the organization and how we are, especially with people in the, in the community. And that had a real big impact on me though. I though I think some of it was, that's why I mentioned the thing earlier about my church background because a lot of that.

Church stuff was like things you did in the community. It was like things you did in the church, whether it was a, a church dinner, community dinner, or, or how your father being, the, being the minister, you know, how he related to people or how my mother and the other, the rest of the women would organize communal.

Events, but with the Panthers, it was like there was just this intentional thing that you're doing this to be a good servant of the people. And that thing about being a servant of the people and that we were the ox and the people rode on our backs and guided us. That was real heavy. That's why I think some of that stuff actually would be leading me [00:18:00] towards later on, towards more anarchistic approaches.

So it was the MAO stuff and then it was the articles you were reading in the newspaper when you would see the men dressed in apron and they're feeding the children at the breakfast program. Or you would see the women with rifles going through that kind of practice. It was saying that we had to change.

You know, if we gonna make this thing happen that we gotta change, that hit me really, really deep in terms of, I wanna be the best panther I can be. I wanna be the best servant I can be. And I also want to continue to keep learning, you know, about these, these, uh, ideologies and then this fight back strategy.

So that I can also be a benefit in that area too, if ever called upon to do so. I mean, I, I just felt like it got me at the right age, [00:19:00] you know, that maybe my machismo wasn't that deep yet and I wanted to be this person that makes this evolution in terms of my revolutionary way of being in this world.

PRINCE SHAKUR: Yeah, I feel like that makes a lot of sense. 'cause I think, um. Growing up in a culture, any kinda space where you see your people being subjugated or you just see people struggle, and then it seems like a lot of what you're describing in terms of what you were learning to admire was kind of like people that moved or acted with meaning.

Like the people taking the guns outta that truck, or your brother and his friends going off to do something or seeing the men in the aprons. It's like this ability to recognize when. You can act outside of yourself and it can be also in line with all these other messages and images and values that you were given or found.

I feel like a lot of young people search for that, but who really gets [00:20:00] it or gets it in the way that you did or in like a very specific like radicalizing context. I don't want

Ashanti Alston: to give the impression that we were all like that. I can only speak to how it felt to me and how I think it felt for others. As time goes on, you'll see that when you feel like some's evolution stops at certain places and yours might still be gone, and then you, you feel like that sometimes it's a little conflict, and I think some of that I probably saw more so in prison.

But even before we get there, so the thing with the Eldridge Cleaver. Thing, me running for vice president and my junior year going into the senior year even, even that Eldridge, controversial, complicated, Eldridge, uh, was definitely a big influence on me even with. Comments he would make about around being anti-sexist and all this other stuff.

But you know, you hear, you heard, you hear all this other crazy stuff, some of you don't [00:21:00] really hear until much later. I liked Eldridge because he was that Malcolm X figure that comes outta prison. He's really brilliant in many ways. He really has a great sense of how to use the media and the way that he speaks to the people, I think appealed to a lot of us.

In the community, especially those of us who were kind of street or sort of kind of lumping or working class because he spoke with such daringness and arrogance towards the oppressors. Sort of like why a lot of people love Muhammad Ali because of the way he talked to white folks via the media. It was like, I'm not afraid of you

PRINCE SHAKUR: turning the camera back on them.

Ashanti Alston: Yes. So that was the elders for me, and it was one pamphlet of his that I resonated with me a lot. It was education and revolution. So he was connecting how we gotta challenge the educational system [00:22:00] from the whole thing with the panthers. I forget what which point it was in the 10 point platform program, but teach us our true history.

Basically, me using that in my speech. I never imagined that the next morning folks would be coming up to me telling me I won. But the fact that I won and the fact that the sister who became the president, she was militant too, but she wasn't even a part of our collective. She was definitely one that had a political consciousness.

But it showed, like still at the time, uh, jihad was one of the leaders of the black student union in the high school. And I say that now because it's like high school. What high schools today would even have a black student union or organized group like that. But back then it wasn't that odd. That student body, a lot of things still resonated.

Whether it was it was what we were doing or the anti-war movement or [00:23:00] stuff like that, there was still that kind of vibe even in our school. Small, small ass playing field. But I won the election. And then after that, uh, me and Jihad were doing our, we are doing our thing and other, and, and others who was a part of the Panther office who were high school student.

We were very active. It just got to the point where that's what led up to when the cop gets killed and, and they're trying, now they're trying to pin the, uh. The death of the cop on me and, and jihad, I think in our minds because we stayed up on what was happening to other panthers across the country.

Typical frame ups or harassments, not fully understanding that there was this counterintelligence program, but we knew definitely that they were on us. Also fully accepting that we ain't backing up and don't ask me why we are like 17 years old. Don't ask me why. It is like we're not afraid. That's one of the things about really believing what you're into, what this is about, but [00:24:00] having all kind of things that reinforce the validity of it.

That is the worthiness of it. And it could be the music, it could be sometimes family, it could be so many other things. It just lets you know that this is right for you. This is what this moment. Wants you to do and you're taking it, fuck all that other stuff. You die. You go to prison. And I know my family, you know, my family was like, boy,

PRINCE SHAKUR: so many intense things.

But did you ever get pushback from the people around you? Do you remember people around you being like, Hey, like you could try to change the world, but look at what I'm thinking of when I got radicalized in high school and my mom, she kept saying. You can want all this all you want, but they killed the people that fought for this back then.

I imagine like the Panther 21 news and trial was like a big thing during this time, but what was your relationship to pushback or how did that show up? Or was it just kind of not around

Ashanti Alston: you that [00:25:00] much or, oh yeah, you could get that from. School. Listen, you could get that from debates in school. You, and we had it all from having debates in school, in the classrooms, outside of the classrooms.

We had that when we would be selling newspapers in the, in the community. You're going to get a debates with people. I'm going to tell you violence is wrong or that, oh, y are y'all communist, or. All these other things, but with family, I don't think it got too much into the ideological. Some of the, some of the things I remember that really sticks out like television.

I mean, usually because of before all of this. You watch Ed Sullivan show, you watch the Johnny Carson show and you know it's whatever, or whatever it is. It, it might be I Love Lucy or something and, and it could always be the family sits in there and watch it. It got to the point where I might be in the living room with everybody, but I got Malcolm X speaks or something I'm reading [00:26:00] and at some point my father would be like, what is wrong with you?

Boy? What is that you reading? Why you gotta read that? Get outta here. I didn't really understood why, but I, I ain't messing with pops. Pops was a former prize fighter, you know, but at a certain point, what my mother knew that of a certain car pulled up front. It is. She had waiting for me if she seen that car, sometimes she would just grab me.

To stop me from going down them stairs to the car and I might have to like make a mad dash instead of the front door to the back door so I can get out. But it wasn't until being in prison when I thought about it, it is like they wasn't really against my being involved or the goals is just different from the Civil Rights movement.

But they didn't wanna see me dead. Or go to prison. But at the time I'm like, man, why are they, why are they doing this to me? Why are they trying to hold me back [00:27:00] in that moment? I took it as you are against me. It was me sitting in prison like, no, they wasn't against me. And they would say, so years later, you know, and stuff like that, that, um, they, they understood that, they respect, they respected me for it.

In the moments it's like you just want them to the support, let's go. But no, no parent wanna see the child like die. It would often come, like that pushback could come from, uh, like the family just really concerned. Or if they're anything, you know, they ain't, they don't want to see you into the violence.

They would prefer the more peaceful stuff, but other folks in the community, you know you're going to get engaged. But that was a whole part of being in this Panther party. The whole thing is, yes, you have to engage people, you have to be able to have them conversations and possibly you might convince people that submitting in all the ways that we do is not the way it'll go.

So when people saw it in programs, like we had a lunch program, 'cause ours started in the summer rather than [00:28:00] during the school year. It took a minute when the children would come in to eat, for the parents to come in and wanna help. But at first they was a little intimidated. But then after they saw it, then they might come in and want to volunteer.

And we realized that this was happening in other, other chapters too, like parents would want to come in and help, or churches would start opening up their door and say, well do it here. Do your breakfast program here. We had a free clothing program. We had doctors and nurses where we could do the free clinic.

That was like, we're actually doing this. We're actually providing an alternative. The alternative just let people know what we've demanding the government do, and they didn't. Oh, we can do this. We can do it on some level. That lets us know that this is what black power can look like. This is what self-determination can look like.

But we are going to have to really fight this system. And those of us coming from the Panther party, we also talking about [00:29:00] we need a revolution. We need to ban with other people and just turn this sucker over. And some people that resonated with others, even if that part didn't, they appreciated the programs.

They appreciated the support we could give or the leadership we could give with rent strikes or with police brutality issues. They appreciated that even if they didn't understand all the other more ideological, theoretical stuff.

JORDAN: What was some of that early day-to-day work when creating the chapter?

Going from like the information center. To chapter path for y'all. Were y'all communicating and like out doing outreach to other militant student groups that were existing at the time? Because like you said, the president was a part of another different group, but also kind of a militant in that era.

Ashanti Alston: The one who won the president, I don't think she was a part of any other group.

She was just really politically conscious. The day-to-day work was like, one of 'em was always selling the newspaper, [00:30:00] but when we had the office. The office is always set up with a certain structure. There's a person called the officer of the day. You're pretty much at that front desk. People come in, you greet people, you know, you let them know where they at, what we do, and all that other stuff.

There might be folks that deal with security. Other than that, whatever work you're supposed to do, whether it is the program, whether you're supposed to be at an anti-war demonstration, or you knew you had certain responsibilities, there was also the political education classes, and there was certain classes that might just be Panthers, but ones that were really important, that ones as open to the community.

Political education is called pe. Weapons training is called te. Technical training, which is not open to everybody best. It's possible members, Panther members would have to learn at least how to operate weapons. And like this is different from California now and California. [00:31:00] They didn't last that long with the open guns because as quickly as Ronald Reagan and them could, they changed that law, made it illegal to carry them guns in the open, but that wasn't the case in anywhere else.

So even in Plainfield fact that we couldn't openly carry 'em, didn't mean that we didn't have 'em. Or didn't have others that would show us at least how to break stuff down, you know, and all that other stuff. And why you used them was always the main thing and whatnot. So there was all these different things.

And you gotta understand too, like there's only a few of our members who were adults. The rest of us, we, you know, you, you had the office, you go back home, other chapters. It may be that. Panthers are living in the same spaces that the office is at or not far away, and it, and a lot of times living there with their children and all the other stuff.

So we didn't have that, but some of the other chapters definitely did. So every day there was things to do still in school, so you still [00:32:00] got your school work and all that other stuff. It felt like 24 hours felt like by the time you wake up to the time you go to bed, you're doing something political or.

Schoolwork, but you're also making schoolwork, political.

JORDAN: Coming into that, how did you feel about gaining, did you have any weapons experience before that and like how did it feel like having that kind of like structured environment, what was kinda like the framework that you felt like y'all were working within?

Like around like justifying, not even like justifying like to yourself of like the. Doing an organized capacity like the mantras or protocols that folks were trying to ingrained in y'all as doing like this organized weapons experience.

Ashanti Alston: What I re, what I remember back then was that there was things we did that kept us with a certain discipline about what our tasks were.

And like I said too, the Red Book was one of them things that played a really big part. It's like we walked around with red books in our back pockets. In [00:33:00] spare time, we could be walking down the street and then we might open up a page and like study this and then talk about this particular excerpt or quotation from mal.

But it kept us with a certain discipline that I guess even today I, you know, when I look back, it was so important. To like have a discipline that you develop a certain accountability, you know, that you had to really think about what you're doing. You had to communicate with others, you needed feedback from those who are more experienced.

Like we would have Panthers come from New York mainly, and just like walk us through what it meant to be Panthers, to the point where. We would go to the main area that we was, uh, we were working, it was in a certain part of playing field black community. It was at the heart of where the rebellion happened and there was this restaurant nightclub called the African Queen.

The African Queen was actually run by a brother from the Nation of Islam who was like a mentor to us, [00:34:00] who had been in the nation for years during the Malcolm Days and every, everything. But he took a liking to us. Even in that space, you're working, you're selling the newspapers, but you got people like him also looking out for us 'cause we are young and like maybe some of the other hustler folks might want to take advantage of us, but it wouldn't happen.

This was the area actually where when I was born, it's the area I lived in. I still look close to a lot of people there, so a lot of people knew me. It was the certain discipline that we had at. We're gonna sell the newspapers, we're gonna make connections with people, we're gonna invite people to come to the office.

And some of them same hustlers that we knew would come to the office every time them things would happen, it would let us know that this approach that we were taking had a lot of effect. And especially with that lumping what we call the, you know, the lumping, that lumping element, because a lot of them just not gravitate towards the civil rights movement.

A lot of them had that [00:35:00] same combativeness towards the system, that same anger that they just refused to modify whatever we were doing, even as feeding the kids. There was that rebellion about them that still allowed them to come and actually become a part of our chapter. It meant a lot for me because it, it helped me to really feel like a revolution from the bottom.

'cause this was different from the Marx. Working class Panthers were saying that lumping could possibly be the vanguard of the revolution, and a lot of that was making me feel like this might be right and we, it was required that we watch the Battle of Algiers and was also required that we watch Melvin Van Peebles, um, sweet Sweetback badass song, battle of Algiers and Sweet Sweetback were both.

Lumping were the main characters, Alban of Algiers, [00:36:00] much more focused. He went directly into the Algerian liberation struggle, whereas Sweet Sweetback was just a, a lumping cat that, uh, was very rebellious, but all of his acts in the community was against the system, but he just had no political direction.

And it just highlighted that if cats like him had the political direction. That on so many levels, you had someone willing to be a servant and someone willing to be a warrior at the same time. You could almost romanticize a person like that. And I know like for me, coming from that, that type of hood, I did romanticize that kinda lump and figure because I had one or two in the family who was sort of like that.

Those things really impacted me deeply and one, and that's where I feel like. There was so many structure ways, Panthers had things structured that there was a role people to [00:37:00] play from all kind of different levels in the community or different functions in the community. It just made sense.

PRINCE SHAKUR: I think it's always useful for us to hear.

The specifics and all the particularities. I mean, there's so many dynamic modes of organizing that y'all are doing. One, I'm curious about how the education was both useful, but also how you or other folks had to kind of stretch beyond it. How this like beginning chapter of organizing led to you and jihad kind of being set up and, and like those frame up charges and how that led to your work with the BLA.

Ashanti Alston: The frame of charges. Man, it was really simple in reflection. Me and Jihad was like the main organizers say most of the members was high school students like us. They were our friends. Jihad lived in the East End. I lived in the West End. So you had a combination of, of brothers and sisters from both [00:38:00] sections coming to join this chapter and you had a few adults, JHA followed.

There was a brother that just came back from Vietnam who was a chef. He was the one, like whatever food we brought him for the kids' lunch program, my man made that into a gourmet meal for these kids. We had things like that going, but a lot of it was, you know, like me and Jihad, we in the schools, we in the streets with our other younger comrades.

But I think clearly if the police is looking at it, they would see that me and Jihad is. Our energy. We never found out what was the deal with the cop getting killed. Not that we even cared, but when they arrested us, we were going to court for burglaries. Some of the things we used to do. To get monies for the free lunch program where we would burglarize white people's neighborhoods, take stuff to the fences for maybe the people would listen that don't, if you bring certain goods to the fences, the fences are the people that [00:39:00] would buy your goods from you and resell your goods.

So if we getting some stuff that might be of value from outta these white houses. We take 'em to the fences. Now we got enough money to go to the supermarkets and we got the food for the free lunch program. Whatever we didn't make from selling the newspaper as panthers, you're not supposed to do that.

Clearly un panther behavior. But we are like 17 years old. Y'all were innovating. Innovating. We were against Panther rules. The reason I bring it up is because it is like. The Panthers were really clear, like you gotta be in the community. You can't be doing other things that jeopardize you getting arrested and stuff.

But we did because the whole thing was you are servants of the people you need to be doing your work in the community. We had got caught in one of 'em, so we going to court, we went separately. I think I went first. He, he said he think he went first, but it doesn't matter When me and my mom walked into the court building, police comes out, Michael Lawson, you're under arrest for the murder of officer.

[00:40:00] So-and-so. My mother just freaks out. I guess the same thing happens to Jihad because now both of us are, are there in the same cell. It definitely catches us by surprise because we don't really know anything about that, but not surprised that it happened, but that we didn't know anything about it. Look at what they do.

The prosecutor, when we had the first day of arraignment, the prosecutor was like, if found guilty, he's moving for the death penalty. 'cause the death penalty was still in effect. And he's also moving to have us juveniles tried as adults. So we were the first juveniles in, uh, New Jersey to be tried as adult and to be facing the death penalty.

It did a lot to disrupt the work. Of our Panther chapter. Unfortunate, but it did, you know, because we were like the key people. Jaha, pop, gotta do everything he can. Him and his family can to get a lawyer. My family gotta do the same thing. I'm sure that some of the other teenagers [00:41:00] are our friends and stuff.

I'm sure their parents was like, oh no. No, you're done with that. My family was able to get a lawyer from like this black law firm in New Jersey, which was, it was like the top black law firm. The top lawyer in there had a reputation as being, he was bad and he had defended other cases, political and not political.

He wasn't able to be the one to take the case. He assigned it to one of his other lawyers who was. He was bad. He was like, great Jihad had a public defender. The work that my lawyer was able to do in showing that this was like a classic frame up was what won this for us. I mean, convincing an all white jury too.

'cause me and Jad was just like, oh no, we gotta get up on add here, man. We not waiting around, we not, you know, all that stuff.

PRINCE SHAKUR: What, what were some of the things that the lawyer was able to like, push through or what do you remember of the strategy that made it clear to the jury?

Ashanti Alston: What the [00:42:00] prosecutor was relying on was they had raided our houses and, and in mine they took a lot of my literature.

A lot of my books and stuff, and one particular book I had was called War of the Flea, which is all about Gorilla Warfare A around the world. And I had stuff underlined and all this and stuff, and he blew that shit up big. And you were like, oh, oh dear. To present to the jury, right? And so his main argument.

Was state of mind. This proves they did it because he's underlining stuff about this and whatnot, right? My lawyer was like, no, that's bullshit. They can read whatever they wanna underline, whatever. That state of mind thing. He really tore that to shreds. But the main thing that won his case was that we had an alibi.

I don't even think me and Jahad realized it because one of one of JHAs best friends, who was also my friend. [00:43:00] White guy. I was over their house when this thing happened because, and I was there having dinner. The mother remembered when they put our friend's mother on the stand. She's one. She was one of them.

Poor working class white woman. You couldn't shake her. From what she knew. And as much as the prosecutor tried, it was like, no, she knows because it was her first time meeting me. And so a, after that the case was done, you know, here we are now we gotta wait for the jury's thing. And it's so funny 'cause as far as what I remember, me and Jahad, I don't know how we gotta hacks all day, but we are we trying to get them bars?

We ain't waiting around, but it was what it was. We couldn't do it. When they said, okay, it's time for the jury. We looking for the worst. So you're prepared. Yeah. I was looking for the worst. Worst. Trying to get out before they make a choice. Yeah. Yeah. So, and, and so and so in the courtroom, they found us not guilty, you know, like Right on and know and so, so then we get released, [00:44:00] and this was a 14 month period.

The other prisoners had big respect for us. There was even a one or two guards. That had big respect for us and that was a good feeling too. And we was able to even do some things proactive for making them extend the visits and all this other stuff. But, um, so getting out. Back in playing field, but we getting some threats from the police that's coming.

Right. And the families want us out. So that's when that, at a certain point, uh, jihad family, they hook him up with an organization in Rochester, New York, and my family being from Greensboro, North Carolina. My family sent me to North Carolina, you know, so to get outta playing field, I was in Greensboro for maybe six months or more.

Come back to playing field with my girlfriend at the time, who was also a part of our chapter. We restarted the chapter in playing field and reestablished connections with the other chapters and from New Jersey [00:45:00] to New York. And so it was then that as things developed, there was BLA action and one of the ones being that after the assassination of, uh, George Jackson, there was B-L-A-B-L-A actions in retaliation in California.

And so also there was actions, BLA actions in New York and in other places. Several of the ones that was in New York was also wanted. California for the George Jackson stuff there. We knew they would be facing the death penalty and all that other stuff too. At a certain point I was approached. Tell people at this point, you know, Safi, who I LA had later married, she was that above ground connection to the underground and she was in charge of the Harlem office and that was the office at, I was back and forth from New Jersey.

Playing field to Harlem and then pretty much Harlem. And at certain point she, uh, approached me about becoming a part of a unit of the Black Liberation Army [00:46:00] with the specific purposes of getting our comrades out of the Manhattan House of Detention, also known as the tunes. And that was to get them ones out that was wanted in California before they would get shipped back.

So that was my entry. Into the BLA, but when I look back on it, I can see that the term that you y'all use now, I'm saying y'all vetting, I guess I was being watched and judged, and I assume others were because the cell that they brought together, we didn't know each other, but we only knew what the mission was.

So at that point you had to kind of phase out the work you were doing, whether it was playing field or the Harlem office, you had to just start distancing yourself because eventually it is just going to be the underground.

JORDAN: And what were some of your guiding mindsets or principles when considering that?

And I'm kind of curious if any organizing, while you were, 'cause were you in jail during that 14th month [00:47:00] period for the frame up charges?

Ashanti Alston: The 14 months was for the frame up.

JORDAN: That's kind of like when the Prisoner Liberation Movement, incarcerated liberation movement started kind of popping up around the tombs and then traveling around through jails that they were transferring people through.

Um, I know you were in New Jersey, so probably not. I'm kind of curious like what that like experience, culture, kind of any shifts in that were, if you were able to do. Any organizing while locked up or any community making or seeing the different structures that were there, how that influenced your kind of thinking?

Coming right back out

Ashanti Alston: in New Jersey around the frame up. This is all Union County jail, the 14 months. Um, it was interesting that me and Jihad, we were continued with the political education of ourselves exercising, training in, in our mindsets. You know, for anything. It was our relations that we would have with the prisoners that we felt like we were still organizing.

That's why at one point we would get visits. Our visit was like a little bit longer than the [00:48:00] regular prisoners, still the juveniles in the adult jail. At some point, we helped the, I think it was a petition or something we developed with them, that we presented to the warden. They're like, yo, why can't everybody have 30 minutes to visit instead of 15 minutes?

You know, surprisingly we won. We was able to help to get the prisoners. All of them had more time, 30 minutes. It was that kind of solidarity that we was developing in there. And, and I'm sure a part of it was that them being older, they was also looking out for us. And that meant a lot. That meant a lot.

There was a brother that got locked up, uh, while we were in there for killing his father in the middle of the street, and the case was. Which he told us that he saw himself as being in the revolution. He kept having these big disagreements with his father, and at some point it drifted out into the streets.

He, at some [00:49:00] point, lost it, pull out his gun, and shot his father and killed his father. And so he was in there with us and I feel like me and Jahad was a, a help to him in terms of just holding onto his sanity. Because it really fucked him up that it came to that. He really felt like he just lost it. I mean, at this point I, I'd have to ask Jahad, but um, what actually happened, I mean, I know he got found guilty 'cause it was right in broad daylight.

But the fact that we was able to give him some kind of support, uh, let him know that we was there, like it's okay. That helped him to kind of just hold it together mentally. 'cause we could see that he was getting ready to lose it. So it was things like that and the ways that other prisoners would help us.

It could be around food if we needed extra food or stuff like that or whatnot, that there was that kind of atmosphere that we helped to create. Because of our situation and, and the respect that people had for us. Now coming out, not only are you restarting the [00:50:00] Panther chapters, but Panther chapters are always connected with political prisoner support work.

Especially when I'm back and forth to Harlem. It's definitely me doing much more direct. Political prisoner work. 'cause with Safi and them, that's like the core, you do work for your political prisoners. You, it's not only the breakfast programs and the newspapers and having an office set up for people coming in, but support the political prisoners.

So we are writing, you know, you're writing the political prisoners, you're going up to visit them. And so it was things like that was going to actually lead to, I guess at some point me being looked at as somebody that could. Join the ranks of the BLA later on down the line with the bank exp appropriation and three of us getting captured.

If you're in prison, you're still doing the work. It's just a different battleground. You're still doing the work wherever you at, if you're in the jails, going through the the court process because before you actually get convicted and sent to prison, you're doing the work, you're educating, you're [00:51:00] organizing.

You know, it's just different when you're in the prison. 'cause now you know you're in set places. You can be there for a while. You could actually develop more organizational things and the jails, it might not be where you can develop something that's gonna sustain itself. If anything, you might want to.

Direct people who might be getting out from the jails or where they can go to get involved if they want to. If the things that we've been talking about resonates with you, the Panther office is here, the other organization that if, if they resonate with the nation, Islam or whatever, wherever you're going do that.

So that you don't stay doing those things that really don't help us to move forward. Could you talk

PRINCE SHAKUR: about some of mindset shifts that were happening? You said you were going back and forth to Harlem and then trying to phase out of your kind of above ground work to the more underground work. Could you talk about what that shift?

Like or what being a [00:52:00] part of the BLA meant to you personally? Or like how did it differ from your work in the Black Panther party? Because so many people read about that, but to actually experience the shifting from one world to the other, could you kind of talk about that and what that involved?

Ashanti Alston: I think this is when you really thinking about death, if you're moving from above ground to under, you really gotta think about death.

At least it doesn't have to be death in a negative sense, it's just that you kind of embrace that it can happen. And I say that because one of the things that a lot of us read was a thing called, uh, the re revolutionary Catechism. And, and, and it's a, I don't know if, if it's true that it was actually written by an anarchist or a person back in the Russian revolution.

The whole thing starts off with the first paragraph it was, which okay. Of the solution. It was, he was a

JORDAN: dick snitched on his [00:53:00] fucking friends. He ended up being a fucking asshole, but Okay. Pop on him. Nah, nah, they still good Victor. You know, he still, he, he read a couple, he wrote a couple of other dope things about state surveillance.

Ashanti Alston: Okay, wait a minute. I know what you want, you're talking about, but it's not Victor Surge. I, I, no, it's in the look in my thing. It's not Baku.

JORDAN: Koon, actually. Okay. The

Ashanti Alston: revolutionary is a doom man. That's the first paragraph and the first thing that's just interesting that you remember all of that. The first sentence is telling you that you being in this struggle, if you're really going to be in it, you might as well accept that.

Because all them struggles that even the the guy who wrote it and all them back then, they're telling you from what they know if they went up against the czar or whoever, expect that your ass going to get killed. If you can accept that, and this is what I feel, I feel like it frees you in a way to [00:54:00] do the things that you need to do.

If you are constantly hung up on this death that you see as something just like, oh my God, how horrible. Only thing you wanna do is avoid that. What I think with the revolutionary catechism is almost like if you wanna come alive, if you wanna really live, embrace that part, and now move on. Do what you need to do.

And so for someone who is going underground. I felt like that was so important. You're acknowledging that you're going to another level. You're going to have to change a lot of your thinking. You gotta change your whole identity. You're going to be leaving family, and none of that is easy. One example around the family thing is like my girlfriend at the time, she was pregnant and she did not want me to go.[00:55:00]

But I'm like, I gotta go. It took me sitting in prison too, because I felt like we gotta do this. You know, we got chil, now they've got a children child, a child coming. We gotta change this world so that this child come into the world free noble. But other reality is I left her pregnant and the child comes.

At this time, I'm still kind of back and forth. Harlem playing field, not fully under, but then when I am fully under, I find out that she's pregnant and then again, and then about, captured in about, I wanna say maybe six months later or so, she has another child. And so I have to sit in prison at some point.

Like, okay, I, I know I did this for the right reasons in my heart. The other reality, I left her with two kids and my family was definitely support. But I still left her [00:56:00] and she carried that. Listen, right now she's, she's like a cat with nine lives. She lives with her husband in Phoenix with my daughter lives in Phoenix with hers.

It was like for the six or seven times she's been on her deathbed to the point where she's been sick for a while and the hospital's like, you might as well just put her in the home and let her go peacefully. And that's what, you know, they had to do. But then yet again, she recovered again. But I, and I say that o only for this, for years, whenever her and my children might get into a political argument, she'd be like, oh, you're just like your daddy.

You know? And not in necessarily a negative way, but 'cause both my children are politically conscious as well, but even me seeing this her, this last year. Before she got sick again, she let me know that it was okay. 'cause I think she know that I still, I really am sorry that I did that. I didn't mean it, [00:57:00] you know, I, I, those were the decisions I made to make them decisions going under.

It's not just you, it really does require you to do a lot of thinking, you know, but I'm, I am just also very clear to this day. We can't be free if this monster breathes, if the monster lives, if the structure is allowed to continue and we keep just avoiding many of the things that are necessary and it just keeps growing and growing.

It might be cancerous and everything else, but man. The only way that we are gonna bring this down, it's gotta come from so many directions and dimensions that it has to die in order for us to really breathe and be able to live and create the [00:58:00] lives we know we deserve. It has to, and I, and it's hard for me to get that across to people because of the death thing.